Issue 141, Winter 1996

Photo © Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard University

Helen Hennessy Vendler was born in Boston in 1933. She studied chemistry at Emmanuel College, a Roman Catholic school for women in Boston, and went to the University of Louvain after graduation on a Fulbright fellowship. She took her Ph.D. at Harvard in 1960 with a dissertation on Yeats, and the following year began teaching at Cornell. She later held regular appointments at Swarthmore, Haverford, Smith, and Boston University, as well as a Fulbright professorship at the University of Bordeaux. In 1981 she joined the faculty of Harvard. In 1990 she was given the title of Porter University Professor.

Vendler’s academic successes have been complemented by numerous appointments in non-university settings. She has been consultant poetry editor to The New York Times, president of the Modern Language Association, and since 1978, poetry critic for The New Yorker.

Vendler’s books include Yeats’s Vision and the Later Plays (1963), On Extended Wings: Wallace Stevens’s Longer Poems, which was awarded the James Russell Lowell Prize in 1969, The Poetry of George Herbert (1975), The Odes of John Keats (1983), Wallace Stevens: Words Chosen Out of Desire (1984), The Music of What Happens (1988), Soul Says (1995), The Given and the Made (1995), The Breaking of Style (1995) and Poems, Poets, Poetry (1995). She received the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism in 1981 for Part of Nature, Part of Us: Modern American Poets. She has edited two books: the Harvard Book of Contemporary American Poetry in 1985 and Voices and Visions: The Poet in America in 1987.

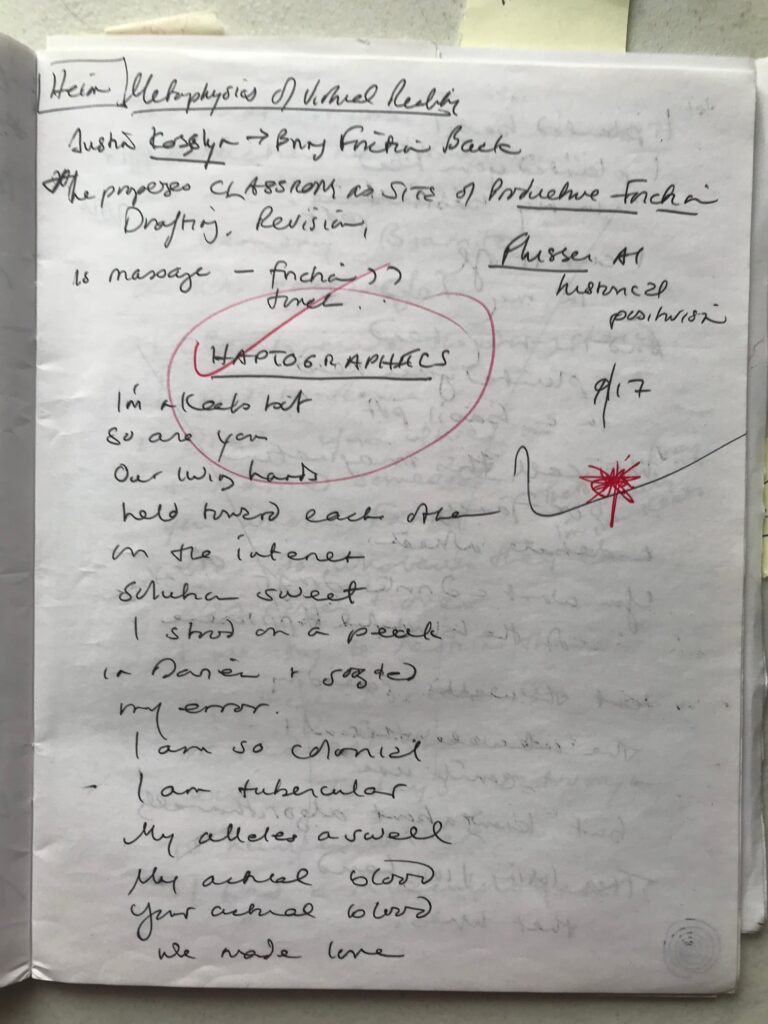

The following interview with Helen Vendler took place in the second-floor living room of her townhouse in Cambridge, a few blocks away from the Harvard English department. Mrs. Vendler wore a loose maroon sweater and black slacks. Around us were the mementos of a life devoted to poets and poetry. “Everything in this room was given to me,” she admitted. As we began our interview, Mrs. Vendler looked weary, but seemed to get a second wind as we continued. She’d awoken early that morning, worried about a meeting with her tax accountant. It was one of many appointments necessary before leaving for England, where she would be in residence at Magdalene College in Cambridge for the spring. After the interview we lingered on her stairwell, where many framed holographs and broadsides of poems—from A. R. Ammons, Frank Bidart, Seamus Heaney, Howard Nemerov, and Stephen Spender—were hung. There was also an occasional poem, a quatrain accompanying a stamped print of a peacock, received from James Merrill. And there was a poem, sent along with a dollsized gavel, from Elizabeth Bishop, when Mrs. Vendler was elected the second vice president of the Modern Language Association. An expression of anxiousness came over Mrs. Vendler’s face as we looked over this large wall of mementos, until she asked, like a concerned parent, if she had forgotten to mention anyone in her interview.

INTERVIEWER

Under the burden of manuscripts to read, letters of recommendation and endorsements of tenure to write, and student papers to grade, when do you find time to write?

HELEN VENDLER

I always write after I think for quite a long time, so the actual writing time is rather short. I think a lot of the work gets done when you have something on your mind while you’re doing many other things. Your unconscious mind is turning this over and over underneath, and then one morning you wake up with a whole lot of things formulated that you haven’t been consciously working on. At that point you can sit down and write. So, it’s not that it takes very long when I actually do it, but it takes quite a long time to work up to it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that your teaching has helped your criticism?

VENDLER

Oh, it would have to, if only because you learn more poems by heart every year from teaching them. They work on you then in a different way from the way they work on you when you’re reading them off the page. They live in you in different rhythms and come to mean more when you know them by heart.

INTERVIEWER

Do you write for a particular audience?

VENDLER

No, I write to explain things to myself.

INTERVIEWER

So your audience is yourself.

VENDLER

Well, I think of my audience in part as being the poet. What I would hope would be that if Keats read what I had written about the ode “To Autumn,” he would say, Yes, that is the way I wanted it to be thought of. And, Yes, you have unfolded what I had implied, or something like that. It would not strike the poet, I hope, that there was a discrepancy between my description of the work and the poet’s own conception of the work. I wouldn’t be very happy if a poet read what I had written and said, What a peculiar thing to say about this work of mine.

INTERVIEWER

No poet has ever done that?

VENDLER

No, not yet. I should add that they may have been too polite to say that.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think your criticism is hard to read?

VENDLER

I think that a lot of things are hard to read if you’re not in the vocabulary flow of that particular discourse. I sometimes forget that even though the words I’m using are fairly ordinary words, the concepts around which they cluster, which are the long concepts of literary tradition, may not be familiar to an audience. People who write about science for the general public also have to think a little about making certain concepts clear that would be second nature to anyone in their labs.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think of yourself as the heir to a particular critic? You worked on your Ph.D. with I. A. Richards, didn’t you?

VENDLER

No, I audited two classes of his when I was in graduate school at Harvard. The chairman would not permit me to take Richards’s class because Richards was based in the School of Education, not in the Department of English (Richards came to Harvard on a Carnegie Grant developing Basic English). His course was scratched off my program card by the chairman, and Chaucer was sternly substituted for it. Nothing daunted, I simply audited a course and a seminar from Richards. He certainly was the most important influence on me, except for John Kelleher. They were the two most indelible teachers that I had at Harvard—I. A. Richards because he gave full weight to every word in a poem and might track the history of a word back to Plato, taking it back through various philosophical and literary associations until the whole historical and cultural richness of the word was exposed. And John Kelleher, because he saw the human situation from which a given poem would arise; since he was an historian, he noted the political situation, or the social situation. In each case, in his class in Irish poetry, the poem was seen to spring out of the trial, struggle, relation of events in the history of Ireland. So in those two ways—both contextualizing ways, historically contextualizing in the case of Kelleher, and philosophically and literarily contextualizing in the case of Richards—they influenced me. They were both magnificent readers of poetry aloud.

INTERVIEWER

How would you describe the hybridization of those two influences in yourself?

VENDLER

Oh, I’m far less contextual than John Kelleher. You of course learn what you need to read a particular poet, as I learned something about Rosicrucianism and the history of Ireland and occultism and Japanese No drama, say, to write about Yeats. You couldn’t not get up those contexts, but for me they are only the groundwork, not central. I’m far closer to Richards, though I am much less philosophical than he was. I think I see words in their literary connotations, but not so much in their philosophical history as Richards did.

INTERVIEWER

As you age do you find yourself valuing different kinds of poems or different traits of poems?

VENDLER

I don’t believe that poems are written to be heard, or as Mill said, to be overheard; nor are poems addressed to their reader. I believe that poems are a score for performance by the reader, and that you become the speaking voice. You don’t read or overhear the voice in the poem, you are the voice in the poem. You stand behind the words and speak them as your own—so that it is a very different form of reading from what you might do in a novel where a character is telling the story, where the speaking voice is usurped by a fictional person to whom you listen as the novel unfolds.

In terms of reading different poets as one gets older . . . I’ve been reading old-age poetry for so long, I feel as though I had the poems before I needed them in terms of life, but I certainly needed them in terms of art. I needed “The Auroras of Autumn” when I was twenty-three; and you always need art that is good no matter what its theme, at all ages. So I wouldn’t say that I’m now looking for old-age poetry. The only time in my life that I remember looking for poetry, because I didn’t already have some in my head, was when I became a mother and I was looking around for poems about motherhood. I looked, but I didn’t find any except Sylvia Plath’s. Hers were the only ones I knew, and they meant a lot to me then, especially those beautiful ones about her child waking up in the morning, or herself getting up at night and hearing the vowels the child utters, rising like balloons.

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel confined in any way as a critic?

VENDLER

Well, Barbara Smith once said to me, But, Helen, you’re so narrow. And I said to her, What do you mean, Barbara? All of lyric from Shakespeare till now? And she said, Oh, you know what I mean. And what she meant at the time was that I wasn’t doing theory. From one perspective, so-and-so’s book may seem narrow, while it may seem very deep and rich to someone else.

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel confined as a female critic in any way?

VENDLER

No, I don’t think the mind is gendered. I know that’s not a popular position these days, but I never felt the mind to be gendered and perhaps that may be because I always read poetry. When I was a young girl reading and the page said, “My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains my sense,” or, “So are you to my thoughts as food to life,” it never occurred to me that these thoughts were not available to me because they had been uttered by an author who was male. I didn’t care who had uttered them. They seemed good things to say at a given moment. Now, I know women who’ve had very different experiences when they were young; I’ve heard many people say, I never found myself responding until I came to . . . And it might be Jane Eyre, or it might be Wuthering Heights, or it might be Emma. I finally realized that those women were novel readers, and what they were looking for was a story like their own story, or a story in which they could imagine themselves playing a role. Of course, if you are a girl reading Oedipus Rex, there is no role for you to play as hero. So if you have a naturally fictional imagination, you might say, That’s not a story into which I can walk. But I didn’t have a fictional imagination, so I didn’t run into that particular difficulty.

INTERVIEWER

Is there anything you fear as a critic?

VENDLER

I fear giving short shrift to something that is really very good, which I don’t recognize at the time. We all know critics who have done that: the critics of Keats who told him to go back to his apothecary pots; the critics of Stevens who thought he was a dandy; the critics of The Waste Land who thought it was a hoax; and perhaps, myself as a critic, say, of Pound, about whom I’ve never written, whom I think of as a minor poet of the fin de siècle and the early century. I don’t admire the Cantos; perhaps that’s a big blind spot in me since there are certainly many exquisitely gifted readers and writers who have admired the Cantos. But I can’t. I’ve tried over and over. As Pound himself said later on, “I cannot make it cohere,” and they don’t cohere for me. Perhaps I’m missing a great body of work because of some defect in me. That’s not how I see it, but it is how others see it.

INTERVIEWER

What about as a woman, is there something you fear?

VENDLER

I have always feared the criticism that the world offers you when you’re a woman who is not conventional. In many ways, I am conventional: I have a conventional-looking house, I wear conventional clothes, I don’t do terribly unconventional things in public—so that I might to some appear conventional. On the other hand, given my upbringing and the expectations of my society, my behavior was not conventional. And I felt isolated and alienated. I still experience that feeling of being alone in a room when no one in the room is like you.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think the content of your reviews ever grows as a result of your own language instead of a poet’s?

VENDLER

Oh, no. My language is so much the inferior of the poets’. Even a minor poet has far greater gifts of language than I have.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think you have ever either overpraised or damned something?

VENDLER

Well, I know there are people who think I’ve overpraised things. I’m sure Randall Jarrell would have thought that I overpraised Stevens’s long poems, since he found them humorless and elephantine. And I’m sure people have thought there are contemporary poets I’ve overpraised.

INTERVIEWER

But none that you have changed your mind about.

VENDLER

No, I think people I have admired have worn remarkably well over the years, whether they are uneven poets, as some of them are, where I like some works better than others, or whether they maintain a consistently high standard as, say, I think Seamus Heaney has done, volume after volume.

INTERVIEWER

And an example of an uneven poet would be?

VENDLER

Ginsberg, for instance, where I think there are always wonderful poems in every volume but the volumes are very uneven in poetic quality. Nonetheless, the people I have written about the most seem to have had good staying power for me over the years. I think of the earliest people I wrote about—probably Lowell, Rich, Ginsberg, Merrill, Ammons, Bishop—all of them have the power to maintain a critic’s interest over many, many years.

Usually, I think there’s nothing to be said about mediocre poetry. It’s like being a talent scout for an opera company, when all you can say about the voice you hear is, No, it has no carrying power, it hasn’t any capacity to stay on pitch, it hasn’t any sense of innate rhythm, it hasn’t any expressive color, it hasn’t interpretive power . . . it’s just no, no, no. If you’re a talent scout, what you like is to have a voice come along that not only has interpretive color, carrying power, and musical intelligence, but is also distinctive in timbre. Then you can say a lot about the voice. When qualities are not there, it is very hard to describe, since you’re describing absences. When the qualities are there you delight in showing how they’re deployed.

INTERVIEWER

When you read a poem, do you see meaning or hear language first? Or, to put the question another way, are you aware of subject and theme first or does style, voice . . . the way words rub against one another engage you first?

VENDLER

I think what hits you on the page is different with different poets. I remember the first thing striking me about Stevens was hearing his voice on a record. Suddenly, this voice was unspooling. I didn’t even know what the poem was about. All I knew was that there were these wonderful lines that I would never have willingly walked away from. I went out and read all of Stevens. So it can be a voice that grips you, that is doing something with language long before you know the theme. In the case of Jorie Graham, it was reading some poems in The American Poetry Review and hearing a new rhythm. I am convinced her rhythms come from Italian, or maybe from French; it’s some foreign rhythm that she has brought into English. I hadn’t ever heard that rhythm before. I don’t even remember now what the poems in APR were about; I only remember the new rhythm that was not known to me before.

INTERVIEWER

Does a poet come to mind whose theme first riveted you?

VENDLER

Yes, but I think it was because it was very well done formally. A Change of World, Adrienne Rich’s first book, was given to me as a present by the woman I worked for, the registrar of Radcliffe College (I was working as temporary office help). She gave Rich’s book to me when I left her office after the year I had worked for her. When I sat down and read it, it was just astonishing (as I wrote later) that someone my age was writing down my life. That was an immediate thematic connection with an American woman of my own generation who was writing down love poems, family poems, that were gripping to me. The one that struck me the most was a poem called “The Middle-Aged,” which was about living in the house of your parents and not thinking of it as your own house. That was the way I had felt about my parent’s house; I couldn’t believe someone had written that down.

INTERVIEWER

Yet, I’ve read that you think of yourself as among what Roland Barthes calls “explorers of the bliss of writing,” as opposed to those who look for meaning, import, philosophy, social truth. Is this true?

VENDLER

On a spectrum of a to z, yes, I think so. It’s not that I’m indifferent to meaning. Reading the Rich poem about parents and children was transfixing to me at that time when I so badly needed explanations of relationships. But I think you come to need explanations of the world somewhat less intensely after adolescence, when you make up a world picture of your own. Though with each crisis that you come to, when the world has to be reinterpreted . . . for instance, the first real death you encounter . . . you go back with that same hunger looking for someone to interpret the event for you. I still feel that with poets older than I, that they’re interpreting the next stage of life for me. Certain ones I’ve come to depend on for that—Ammons, Ginsberg, Merrill. When Merrill died, I suddenly felt a terrible depression as I realized that he wouldn’t be there to tell me what life was like between seventy and eighty, so I wouldn’t know before I got there. Each one tells you something slightly different. It’s not that younger people can’t tell you things too. They can and do, but they can’t tell you what it’s like to live between sixty and seventy if they’re living between twenty and thirty.

INTERVIEWER

What about irony? Is it something you prize in a poet?

VENDLER

I don’t think there is any conscious writing without irony, because there is always the irony that you’re writing in the present about something that happened in the past. There’s always a spectatorial irony in a poet of any developed self-consciousness. There is an irony implicit in writing itself. Then, there is the spectrum of the ironic from, say Elizabeth Bishop, who is a wonderfully ironic poet—awful but cheerful—about herself and about her life, all the way down to a rather unironic poet, like Hopkins, of whom one of his school fellows said, Hopkins gushes, but he means it. I like both ends of the spectrum. There are hardly any good poets I don’t like. I think Pound and Browning are the only two poets whom I don’t feel close to.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a low tolerance for humor? I think of a poet like May Swenson who has a real lightness of touch but not so much astringency. Does that explain why you find her less appealing?

VENDLER

Well, I think it’s more that she’s a very visual poet engaging in observation of the natural world, but without as much philosophical or emotional ballast as I would like. I’m not visual enough to be satisfied with a poem of almost pure visualization and registering. I love humorous poems. His humor is one of the things that attracts me to Ginsberg.

INTERVIEWER

Who are the other poetry critics that you admire? I wonder particularly about younger critics like Dana Gioia and William Logan.

VENDLER

To tell you the truth, the people who have been most interesting to me over time have been poets writing criticism; and I wish poets wrote more criticism. Pieces about the state of poetry in the United States, like Dana Gioia’s, don’t interest me. I want someone to take me inside the heart of a piece of writing, and I don’t think of Dana Gioia as writing that sort of criticism. He may have done such work, but I haven’t seen it. Seamus Heaney writes wonderful essays on poetry. I admire the kind of poetry critic that Randall Jarrell was in his pieces for The Nation, and I think of the prose about poetry that Auden wrote, which is so distinguished. I haven’t followed William Logan’s criticism.

INTERVIEWER

Is there an American poet whose criticism you admire?

VENDLER

Louise Glück has written extremely well on poetry. She has just brought out a book of exceptionally intelligent, acute and beautifully written, trenchant essays. Sometimes I like what Mary Kinzie writes. She’s more moral than I like; she often gives more weight to the morality of the poetry than to its vividness. I admire Dave Smith’s passion in his essays on poetry.

INTERVIEWER

What about Rich’s prose?

VENDLER

That has been mostly political rather than critical. I like Richard Howard’s descriptions of some poets, though he does less criticism now than he did earlier. I’m sure there are many others that I’m forgetting to mention. I’ve always admired Calvin Bedient’s work very much. I’ve admired Stephen Yenser’s work on Merrill and Lowell; Stephen Yenser writes as a poet. Calvin Bedient is writing poetry too. I think it’s the criticism of a person who is a poet, or at least has the sensibility of the poet, that I like.

INTERVIEWER

The critic Bonnie Costello was a student of yours, wasn’t she?

VENDLER

No, she was never my student; she was my colleague at Boston University. Someone like Bonnie has a more philosophical and analytic mind than I do, and often brings a more speculative mind to, say, a descriptive poem than I would. I might tend to stay with the level that the poem sets itself and enter the poem at that level, and Bonnie might enter it at a level of the philosophical question that the descriptive poem raises about seeing, and then describe it in that way. She taught me how to read Marianne Moore, and I will be eternally grateful to her for that.

INTERVIEWER

What were your parents like? Did they read poetry?

VENDLER

My mother was a schoolteacher who taught the first grade for fourteen years before she married in 1930. Since in those Depression years married women were not allowed to teach because it would take the money from a breadwinner, my mother lost her job and never had a job again, which was, I think, a great loss to her. She was a great reader of poetry from Shakespeare to Tennyson, and always had very many books of poetry around the house; she quoted poems naturally in conversation. She took us to mass every morning; I was introduced early to liturgy, hymns, Gregorian chant. The schools that my parents sent me to from the sixth grade onward were Catholic schools where we sang the liturgy in Latin, and that was extremely interesting to me. I began to learn Latin by myself in the seventh and eighth grades and then studied it in high school.

My father was a teacher of Romance languages who was bilingual in Spanish and English. My mother was a graduate of Boston Normal School, as it was then called, which was to become Boston State Teacher’s College. My father had graduated from Boston College in 1915, and then had taken a master’s degree in education at the Boston Normal School in 1916, where he met my mother and proposed to her; she didn’t marry him until 1930. Meanwhile, he went off to Puerto Rico and Cuba and worked and taught English there. He first worked for the United Fruit Company, but then became a teacher of English in Luquillo, Puerto Rico. He had kept up with my mother during those thirteen years; eventually he returned when she agreed to marry him. He got a job in the Boston school system and taught Spanish, French and Italian; he also taught these languages to my sister and me. He began a Ph.D. at Boston University but dropped out after having passed his orals; by that time he had three children. Later, he became head of the Romance languages department at Boston English High School. He took early retirement as school conditions declined, but he was unhappy not working, and so became a messenger for a law firm for the last fifteen years of his life, and enjoyed that very much.

INTERVIEWER

Did you write poetry as a schoolgirl?

VENDLER

Yes, I wrote my first poem when I was six, and I went on writing until I was twenty-six, and then I stopped. I had found my real vocation as a critic by then, through writing my Ph.D. dissertation.

INTERVIEWER

What was your home life like as a girl? Is it true there was no gift-giving in the house?

VENDLER

We got gifts for Christmas, but they were books, especially books in foreign languages. I didn’t ever have a doll, that I recall, until an aunt gave me one when I was twelve. Another aunt gave me a brocade jewel box when I was twelve, and I kept it all my life because it meant so much to me to have a present; it was stolen in a break-in when I was lecturing at Berkeley a few years ago, along with the jewelry that was in it. I minded the loss of the jewel box more than the loss of the jewelry. But normally we didn’t have birthday presents. We sometimes had homemade presents. My father and grandfather made me some little furniture. My paternal grandfather was a carpenter. He lived with us from the time I was twelve till the time I was about twenty or twenty-one, and he and my father used to make little things of wood for us. I don’t think there were other presents that I can recall.

INTERVIEWER

Was there a TV and radio in the house?

VENDLER

No, we never had a TV and we weren’t permitted to listen to the radio. We weren’t permitted to go to the movies, either, because my parents thought of those as unimproving ways to spend time, though my mother used to let us listen to the radio the nights my father was out teaching night school. We regularly listened to “I Love a Mystery,” and I liked that very much. I never saw many movies growing up. I read a great deal.

INTERVIEWER

You were a chemistry major in college. Do you think your scientific training shaped your voice as a critic, or shaped the manner in which you read poems? I’ve heard you say that you’re quite literal-minded; is that because of the scientist in you?

VENDLER

No, I think that’s what made me able to enjoy science, because it is so grounded in material reality. What science did for me was to train me to look for evidence. You have to write up evidence for your hypothesis in a very clear way; your equations have to come out even; the left side has to be balanced by the right side. One thing has to lead to the next, things have to add up to a total picture. I think that’s a natural thing to do with literature too. I feel very strongly that anything you say should be backed by evidence from the text, so that you follow a constant loop between generalizations and evidence. I don’t like criticism that is simply rhetorically assertive at a very high level without much reference to evidence in the text.

INTERVIEWER

Do you consider yourself a feminist?

VENDLER

In action, yes. I don’t think of feminism as a scheme of thought, I think of it as a way of life. That is, I believe that I want the good of women in my own profession and in other professions.

INTERVIEWER

You mean in a legal sense?

VENDLER

Yes, I believe women should have equal rights. They did not when I was starting out in the profession. Many schools didn’t hire women. Many schools wouldn’t hire women except to teach freshman and sophomore English. They didn’t allow women to be on the tenure track but kept them as permanent lecturers, even if the women had greater ambition than that. I would like an equal floor of opportunity for women, and that seems to me a feminist conviction. No, it doesn’t seem to me a feminist conviction, it seems to me a conviction of justice. I don’t think you should have to be a feminist to think that women should have equal rights. There were men who thought that women should have equal rights, not because they were feminists, but because they were interested in justice. That women should have justice before the law, should have justice in academic treatment, should have equality in marriage—those are all things I believe.

INTERVIEWER

But in the case of Adrienne Rich, it would appear that you no longer feel that she is “writing your life,” as you once did.

VENDLER

Oh, she is in some ways . . . the sadness she feels about loss that is part of getting older, the appreciation she feels for certain things that she didn’t have time to appreciate earlier. I think in An Atlas of the Difficult World there is a great appreciation of the American landscape, which in a sense she almost didn’t have time for earlier. Now she can actually look in a way that you can when you’re older and you’re not taking care of small children, or you’re not so hell-bent on trying to get something accomplished. I still see many parallels in our lives, and I’m very much interested to watch her decade by decade too, as I always have been.

INTERVIEWER

You have written in an essay on Rita Dove that “no black has blackness as sole identity,” and further “no black artist can avoid, as subject matter, the question of skin color, and what it entails; and probably the same is still true, if to a lesser extent, of the woman artist and the subject of gender.” How do you feel about identity-markers in the teaching of literature today: black studies, gay studies, women’s studies, and the criticism built up around them?

VENDLER

I was never solely drawn to writing about women authors, chiefly because there weren’t that many vivid writers of poetry who were women. And there are many men I am not drawn to write about. I don’t think I’ll ever write about Alexander Pope, and I don’t think I’ll ever write about Emily Dickinson, but not because Dickinson is a woman or Pope is a man. They are not on my wavelength as much as some other authors, and life is short. I’ve never wanted to write about Irish American authors, though I was born and raised in an Irish American community. I’ve never wanted to write about Catholic authors as such, though I was born and raised a Catholic. Those aspects don’t seem to define me. I’m much more drawn to authors that I feel close to by temperament. I feel close to Stevens by temperament. I feel close to Keats and to Herbert by temperament. They are indolent and meditative writers. I don’t mean indolent in personal character, but they like to roam freely in their thinking about a topic, so that Herbert will come back and back to affliction and Keats will come back and back to the sensuous life. Emily Dickinson cuts things off very short, and that always seems to me rather shocking. She ends poems too soon for me. When I think about the poets that attract me, it’s much more because of a deep congeniality than from something that seems to me so superficial as either religion of origin, gender, or ethnicity of origin. Temperament seems to me more deeply fundamental than any of those things.

Now if I were black, I might not feel temperament to be more fundamental than being black, or (had I been Jewish in Nazi Germany) being Jewish, because when your whole life is conditioned by a single fact dictating whom you can marry, where you can live, whether you will have to go to prison, what you can buy and sell, whether you can go to a university or not, that fact colors everything. I think in America today, every single aspect of your life, if you’re black, is affected by that identity-marker. I don’t feel that any of my early identity markers so confined or coerced my life that I had to see my life in terms of it. So many gay people have been repudiated by their families, or discriminated against in jobs, that it too might seem to be an overwhelming identity-marker at the moment in America.

INTERVIEWER

In the introduction to your latest collection of reviews, Soul Says, you speak of the soul and the self in the lyric as different from one another. Could you say a little bit about that?

VENDLER

Well, with the rise of identity defined almost solely through race, ethnicity, or gender, I think we’ve forgotten the identity that speaks when one is speaking to oneself. That is to say, one is more conscious of those things—class, race, age, sex—when one is in the presence of others. It’s the difference principle that makes you consciously say, I am black and you are white; I am old and you are young; I am a woman and you are a man. But when you’re by yourself you don’t need so powerfully to assert any one of those identities; when you speak to yourself, you rarely say, I, as a woman, am saying this to myself, or, I, as a sixty year old, am saying this to myself. You tend merely to say, I am saying this to myself, because in the absence of others you can be yourself without external reference. Lyric comes out of that self that is less socially marked than the self that we normally refer to as our social identity. That’s why I took the title Soul Says from the title of a poem by Jorie Graham, because I think the word soul sums up the speaker of lyric.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think there are any huge movements in American poetry today?

VENDLER

I think of the poetry after World War II as suffused by Freud. Some people call it confessional poetry, but it seems to me to be Freudian poetry. All of those poets—Plath, Berryman, Lowell—spending an hour a week in a therapist’s office made a powerful turn towards the family romance. I don’t think Eliot or Pound would have thought of sitting down and writing about what life was like with Mummy and Daddy at home. I don’t know that the poets I’ve named thought they were living in an era of the Freudian poem. Other poets escape that. You wouldn’t say that Ammons’s poems (though he is of that generation) are Freudian poems; they are not.

INTERVIEWER

Didn’t you once say that in Heaney, and maybe Jorie Graham, and one or two others, you felt there was a trend to go back to some preliterate aspect of life? In Heaney’s case for instance, now that he’d done the family, done the political situation, etcetera, what was there left in terms of subject? There was this desire to go back to . . .

VENDLER

I think I said to the perceptual: that is, who are we when we are living in the sensorium of the world? I think of that question as very strongly present in somebody like Charles Wright, whether he is registering evening over Laguna Beach or a moment in Venice. It’s the influx of many things—the stars, the flowers on the trees, the night wind, the grass at his feet—the total perceptual field that’s being registered. Any slight shift in the field will cause an entire shift in vocabulary to accommodate it; the source of the vocabulary is not what you want to get said in a philosophical sense or propositional way, but rather what the world is feeling like at this moment. That is also present in Mark Strand’s The Continuous Life, where he is doing a very abstract version of the sensorium. It certainly is powerfully there in Jorie Graham.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a place in poems for issues, real-life opinions, and political platforms?

VENDLER

There is a place in poetry for everything. But as Wilde said, something is well-written or ill-written, that is all. To be more serious, it seems to me that all poetry has social value. It isn’t only “protest poetry” that has value for society, though sometimes protest poets think that their protest poems are directly socially useful. Somebody writing more abstract poetry, like John Ashbery or Charles Wright, might not be thinking, Is this poetry socially useful? In my view, it doesn’t matter what the topic of a genuine poem is; it is socially valuable because it is an integration of experience and language.

INTERVIEWER

Are you interested in politics? Do you read the newspaper?

VENDLER

I read the newspaper every day. And I am interested in politics to the extent that I grieve over the imperfection of it. If you grew up as I did in a corrupt state . . . Massachusetts had a machine-politics for a long time, dominated, first, by the white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, next by the Irish. The whole thing was already predetermined and predecided. The machine was very strong, and politics was a self-oiling mechanism. It didn’t have much to do with the will of the people, it had to do with subtle interlocking arrangements between politics and business. In that sort of city, you become very cynical about politics, very young. As long as senators are millionaires, politics will not be just.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have an agenda for American poetry?

VENDLER

I don’t think of myself as being in American poetry. I mean, I’m concerned with poetry, but I’m as likely to be reading Czeslaw Milosz as to be reading Mark Ford, or Dave Smith, or Charles Simic, or you. Sometimes it’s an American poet, sometimes an Eastern European, sometimes a Spaniard. It might be Octavio Paz . . . I don’t much care. I am devoted to English because it’s my mother tongue. I’ll never feel that way about any other language except Spanish, which I have also known since birth. Both of them have resonances of the mother tongue for me, and both of them are immensely moving to me. But I don’t feel a particular nationalistic attachment to American poetry over or against any other poetry written in the world.

INTERVIEWER

Do you see yourself as anachronistic in the manner you write about poetry as a close reader?

VENDLER

Well, I’ve never liked the term “close reading.” I’d like to know who thought it up.

INTERVIEWER

What do you call it?

VENDLER

Reading from the point of view of a writer. The people who in the United States pioneered what is now known as close reading were poets like John Crowe Ransom and Randall Jarrell. But close reading has existed forever. There have been commentators on Homer since the dawn of time; those were the close readers of Homer. I think of close readers as people who want to read from the point of view of someone who composes with words. It’s a view from the inside, not from the outside. The phrase “close reading” sounds as if you’re looking at the text with a microscope from outside, but I would rather think of a close reader as someone who goes inside a room and describes the architecture. You speak from inside the poem as someone looking to see how the roof articulates with the walls and how the wall articulates with the floor. And where are the crossbeams that hold it up, and where are the windows that let light through?

INTERVIEWER

Recently in The New York Times you said, “the canon is not made by anyone except other poets. Long after the tumult and the shouting die, who remembers a single review of Shelley or Byron or Wallace Stevens?” This strikes me as astonishing coming from someone who has spent much of her life writing reviews. What has been your motivation?

VENDLER

I think of the reviews I’ve written as a continuing self-seminar in contemporary poetry. A new poet would appear, and I would want to track the progress of that person, see what happened next. I’m always curious about what poets will do next. That’s why I wrote the Ellmann lectures on the breaking of style. It did interest me very much when, say, Charles Wright after writing Bloodlines would suddenly write something like China Trace. Why was he doing this? What was behind it? Things like that make me sit down and think. A familiar poet doesn’t set the same problem as your first encounter with a brand new writer. It’s the hardest thing to do, to see a book that no one has ever seen before except its author, to say something about it, to investigate it and solve its poetics to your own satisfaction. Reviewing was a way of earning money, but it was a way I really delighted in.

INTERVIEWER

What is your perception of your own power?

VENDLER

I can see that it seems a great deal of power to a young writer to be reviewed or not reviewed in The New York Times . . . as though it could make or break the book. Reviewing may seem like power, but it’s very ephemeral power. Yes, if I review a book in The New York Times or The New Yorker more libraries will buy it, but that doesn’t mean it will be looked on favorably in fifty years. There are millions of books that have been bought by libraries that nobody will ever read again after the year in which they’re published.

INTERVIEWER

I wondered how you felt being depicted in The New York Times recently by a caricaturist as a head on a tank.

VENDLER

I thought it was very funny. My son, much amused, said, My mother is a tank. The odd thing for me in seeing it is that I write mostly appreciative reviews, so a tank armed with a phallic howitzer, or whatever my fountain pen was supposed to be, seemed to me not quite the right representation for the kind of admiring reviews that I normally write. However, since a female who expresses herself decisively seems to this world someone armed with ammunition, it’s probably fair enough.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think people are afraid of you?

VENDLER

“I must be proud to see / Men not afraid of God, afraid of me,” said Pope, satirizing the opposition. One should not fear the exposure of truth, since the truth makes us free. If it is truth, what I’ve written, then it shouldn’t make anyone afraid. If it’s not truth, it has no power, so no one need be afraid of it.

INTERVIEWER

What is your response to the criticism that you reject the romantic tradition and all those American poets that are its literary descendants, like Galway Kinnell, Donald Hall, Theodore Roethke, and Philip Levine, that you prefer instead the poets who are stylists, technicians, poets who are “cool” instead of “warm”?

VENDLER

The poets that I like are unsentimental; the poets that I don’t like are sentimental, very frequently. The poets I think of as sentimental, someone else might think of as descended from the romantic tradition. But there are many other poets who descend from the romantic tradition whom I admire very much. Ammons is a direct descendant of the romantics, as a nature poet, and yet I don’t see Ammons as sentimental at all, far from it. Practically everybody in America descends from the romantic tradition. What I think sentimental is what others think feelingful, and that’s a line that people draw in different places. What is “warm” for one is sentimental for another. And I may have had a more unhappy life than someone else. Someone else may see amplitude and joy where I see self-delusion and sentimentality.

INTERVIEWER

What about the criticism that you favor a poetry of the terribly well-educated?

VENDLER

All good poets are terribly well-educated, otherwise they wouldn’t be good poets. They have to have enormous linguistic command to write poetry well. Someone like Blake who never went to a university, someone like Whitman who never went to a university, who could say they were uneducated? Melville said the whaling ship was his Yale College and his Harvard; for Blake and Whitman, the printing press was a university.

INTERVIEWER

How do poems enter into your life on a daily basis?

VENDLER

They help me to know what I’m feeling. Out of the depths of my heart will come a quotation completely unbidden. And then I will think, Oh, so that’s what I am feeling today. On any occasion when a response is called for, what usually comes to my lips is a line from some poem or other. My son laughs about this and says, A quotation for every occasion, Mom. He doesn’t understand how my first response can always be a line from someone else, but it is. I’ve absorbed so much poetry over the years, that there are just hundreds and hundreds of lines in my mind. And when one of them floats up out of the mass, I know it’s telling me something.

INTERVIEWER

I noticed you used the word body to describe the style of a poem in your new book, The Breaking of Style. Why is that?

VENDLER

Well, there has been so much emphasis on the body lately in critical language. I was trying to think of the way the physical body manifests itself to me—other than in ordinary daily-life ways—I mean, how it manifests itself to me in my consciousness. And I realized that when I know a poet’s writing well, I know it in the way I would know a physical body by sight. It has a contour that changes over time; you feel that the very spare contours of some late Stevens poems are very different, say, from the more baroque contours of some of his earlier poems. And it’s almost as though . . . well, he says it himself in “The Dwarf”:

Now it is September and the web is woven.

The web is woven and you have to wear it.

. . .

It is all that you are, the final dwarf of you,

That is woven and woven and waiting to be worn . . . .

The new body of style, “the final dwarf of you,” is a moral body as well. The body presents itself to me as something that can be given a shape in words. The many bodies in the physical universe are matched for me, and symbolized for me, by the many bodies of the verbal universe.

INTERVIEWER

Then you believe that all poems, in a sense, have bodies and souls?

VENDLER

Yes, the body is the sinew of the language, as when Hopkins said, praising Dryden, that in him you find “the naked thew and sinew of the language.” You feel that the richly opulent Keatsian temperament is different from the briskly social Browning temperament. The body of the verse gives you a sense of an alert, greyhound body in one, and a fluid sensuous body in another.

INTERVIEWER

Does criticism have a body? Do you feel that your body is represented in your criticism?

VENDLER

I don’t think it’s a direct representation of the person’s body. If you gave visual representation to the body of Hopkins’s style, it would probably be more like Felix Randal the farrier, whereas Hopkins himself was frail and thin. So it’s not the physical body that’s represented but something in the way of being in the world that’s represented. I think my way of being in the world is in part an intellectual way and the criticism represents that. Access to the world for me is through both mind and feelings. I am not satisfied with having a feeling unless my mind is also thinking about the feeling, interpreting the feeling. Uninterpreted feeling is for me a painful state.

But I would say that criticism doesn’t have so pronounced a stylistic body as poetry. Even Seamus Heaney’s criticism doesn’t have so pronounced a style as his poetry. Even Randall Jarrell’s criticism, vivid and brilliant though it is, doesn’t have that Jarrellian nostalgic sweetness and infantile yearning that is in the poetry. You can summon up Jarrell from his poetry better than you can from his prose.

INTERVIEWER

In your introduction to that same book, The Breaking of Style, you write, “The forgettable writers of verse do not experiment with style in any coherent or strenuous way. They adopt the generic style of their era and repeat themselves in it.” Yet aren’t there extraordinary examples of poets, like George Herbert, as you point out, who do not break their styles, or change their bodies, to borrow your trope, as in the case of Emily Dickinson?

VENDLER

Well, each case is special. In Herbert’s case, we have an extraordinarily short writing life. Most of the poems are written in the last three years of his life, when he was between thirty-seven and forty. I don’t know what he would have done if he had lived longer, had he done more writing. I can’t think of any long-lived poet who stayed the same all his life. Even Emily Dickinson, who decided to take a prosodic form and keep it invariant, has very powerful changes of style. She goes back and forth between a sort of girlish style, which she uses even very late, and a powerful metaphysical style. I wouldn’t say that there’s no change of style in Emily Dickinson.

Ginsberg seems to me the person who best fits the description of somebody who finds one way of writing and continues to write in that way. But Ginsberg is saved by his really zany, wildly irregular imagination. When you open a new book by Ginsberg, you don’t know what topics will appear in it.

INTERVIEWER

How did you first meet Robert Lowell?

VENDLER

I think I had met him on a few occasions, but I really talked to him for the first time after a reading of James Merrill’s. We sat down and began to talk, and from then on we were friends. We were talking about Stevens, and about Lowell’s own work, and we were laughing a lot; he was a wonderful conversationalist. He said to me, You don’t like “Esthétique du Mal” as much as I do. And I said, No, I like it the way I like all of Stevens, but it’s not my favorite Stevens poem. Oh, it’s my favorite Stevens poem, he said. And when I said, Why? he replied, Because it’s the most like me! It was charming and it made me see “Esthétique du Mal” in a new light; I could see how he and Stevens came out of Baudelaire, and that was the way they were alike.

INTERVIEWER

Cambridge can seem like a very little village sometimes. Do you ever grow weary of the poetry scene here?

VENDLER

I’m not in “the poetry scene” here. That is to say, I’m a native Bostonian, I’ve lived in this area since I was born, my parents and my grandparents both lived here, and my sister and brother, cousins, aunts and uncles, and friends live here. I never felt that the scene that I was in was either necessarily the intellectual scene or the poetry scene. I’m very happy that I will die where I was born; it is a great gift to have continuity in your life. I was out of Cambridge for many years teaching at Cornell and Swarthmore and Haverford and Smith and so on. But I’m glad to be back. I go to some poetry readings, it’s true, but I also go to family weddings and funerals and I also see old friends from Boston University and Smith.

INTERVIEWER

Is there no poet for whom you would like to write a biography?

VENDLER

Oh, no. I couldn’t keep the index cards straight. I’d get all the dates wrong. I’m not an historian, and I don’t have a head for history. Biographies, histories, novels, essays, autobiographies all seem to me less riveting by a million miles than a good poem, and almost none of them are as well written as a good poem.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a favorite among your own books?

VENDLER

My favorite is my Keats book, because it’s the one in which I felt I could give the poems their due. It’s hard when you’re writing about, say, Stevens’s long poems to do justice to a poem that may be eight hundred lines long. When I finished writing on the ode “To Autumn,” which has thirty-three lines, I saw that I had written fifty pages. And I thought, That ratio probably seems excessive, more than a page per line. But it struck me as just about right for “To Autumn.” Maybe it should have even more pages. If I had had to write about “To Autumn” in ten pages, I would have felt pained with frustration.

INTERVIEWER

Do you cook or sew?

VENDLER

I used to sew all the time when I was young. I made my own clothes, made clothes for others. I used to do alterations for everybody in the family. I used to cut hair, do home permanents. I never liked to cook. I was very clumsy in chemistry and used to knock over with an inadvertent move of the elbow solutions that had taken three weeks to make. I can make a dinner, but it’s not something I enjoy, and it’s something that makes me anxious.

INTERVIEWER

Do you collect anything?

VENDLER

Broadsides. I love poems by themselves on a piece of paper. I think all poems should appear by themselves; you should see them one at a time, with only one on a page. When a broadside is printed up, and you have only one poem, it’s thrilling.

INTERVIEWER

Do you like to sing, or do you like opera?

VENDLER

I love vocal music of all kinds. I didn’t have records when I was young, but I used to take opera scores out of the library to transcribe. I didn’t know you could buy paper with staves on it so I used to draw my own staves. Then I’d borrow the score from the Boston Public Library music room (a wonderful resource) and copy down the arias I wanted on my homemade staves and write out the words underneath them. We did have a piano, so I could pick out arias on the piano, and I learned a lot of operas that way. The Ring does seem to me the best and the most comprehensive operatic picture of the universe, yet I’m deeply attached to lieder as the corresponding art form to lyric.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a pet at home?

VENDLER

I’ve always had cats, my family always had cats, my son has a cat. We are not dog people. Right now, my cat is a large, terrified Himalayan named Shiva, who was an abused cat. Because she’s a Himalayan, it seemed to me she should have some kind of Indian name, and because Shiva represents creation and destruction at once, it was a name I responded to and liked.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a motto?

VENDLER

A motto. What an interesting idea! “God and the imagination are one,” from Wallace Stevens? “How high that highest candle lights the dark”?

INTERVIEWER

Do you like to travel to certain places?

VENDLER

I like to have seen the world. D. H. Lawrence once said one wants the experience of having been married, and travel is like that. Travel is often agonizing in the process, but in retrospect it’s so revelatory not to have a blank place on the map. Before I went there, Hungary was just a large blank spot with nothing in it, and now when I see it on the map, I remember the Danube bend and Esztergom and Lake Balaton and beautiful fields, and the river and the chain bridge.

And the same with China, China was nothing to me until I went to China, and I’m forever grateful . . .

INTERVIEWER

You went to China because your daughter-in-law is Chinese?

VENDLER

No. I took my son to China with me when he was a college senior. He enjoyed it so much that he wanted to go back; so he went back and taught English, and met his wife there.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a living person you most admire?

VENDLER

It’s more a plethora than a dearth. I mean, I admire so many writers. I feel extraordinary grief when I lose one: I still mind terribly having lost Lowell; I still am feeling acutely the impact of having lost Merrill. And the impact of having lost Sylvia Plath, though I never knew her. Then there are moral heroines and heroes that I admire.

INTERVIEWER

You mean that are not poets.

VENDLER

Yes, totally inconspicuous people who have led exemplary lives.

INTERVIEWER

Friends of yours, or public figures?

VENDLER

Some of them are teachers, some relatives, some friends. I don’t know personally any public figures; I don’t think of them so much. I think of the uncomplaining, of the remarkably generous, of the witty. What would we all do without the witty?

INTERVIEWER

Is it hard to be friends with poets whom you do not admire?

VENDLER

I don’t think I’ve ever been friends, exactly, with somebody whose work I don’t admire. My closest friends have not, on the whole, been poets. They have often been other women bringing up children . . . relatives, friends, literary women, colleagues.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that knowing a poet could interfere with your assessment of him or her?

VENDLER

I don’t think so, because I have been assessing poets since I was about fifteen. When I was a girl, I used to go to poetry readings at Harvard, and I would sit in the audience listening to Dylan Thomas, e. e. cummings, T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, whoever happened to be coming through. I think that the assessing of poets is a quite impersonal act that usually occurs spontaneously as the poem rises off the page to meet you. And you are either repelled by it or attracted by it, or are indifferent to it. The poem is something quite other than the person who writes it.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever had a confrontation with a poet you reviewed?

VENDLER

Yes, it was a poet whose criticism I had criticized. I had said that he had a tin ear, which is something a poet doesn’t want to hear. And I’ll never forget his response. At the time I reviewed him, we had never met; later, we were both at a party. When we were introduced, he laughed with gaiety and said, Ah, a hostile reviewer! I was so taken by the generosity of his response that, of course, we became friends. I still think that was a remarkable response.

INTERVIEWER

Are there writers you’d like to have known?

VENDLER

Keats, of course. Everybody would have liked to have known Keats. Shakespeare.

INTERVIEWER

What about recent writers?

VENDLER

I wish I had set eyes on Stevens once. It grieves me that we were alive at the same time, but that he was dead before I read him. I would have liked to have seen his face and heard his voice, just to have had an immediate sense of his character.

INTERVIEWER

Why do you think it is that prosody, lineation and grammar are not much talked about by critics?

VENDLER

Well, we don’t have rhetorical training any longer in the schools—the extraordinary rhetorical training of the study of Latin, translation from Latin. We’re missing all of that fantastic elaboration that even the grammar school student in Shakespeare’s time went through. The sense of etymology that came from Latin is missing; the sense of English grammar that came from diagramming sentences has gone. What you have not been trained to recognize, you don’t see. We don’t see certain figures of speech that were once commonly known, because we’re not trained to recognize them. It’s a matter of bringing poetic means to consciousness. Knowing another language helps to bring them to consciousness, translation does; but these are not common features of schooling now.

INTERVIEWER

What about creative-writing workshops, do you have an opinion about them?

VENDLER

I’ve only sat in on two single workshops in my life, so I certainly couldn’t have an opinion. One truth that is rather neglected in creative-writing workshops is that all good poets of the past, almost without exception, were at least bilingual if not trilingual.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think there’s a subject that is taboo in poetry?

VENDLER

Subjects are rarely taboo in poetry these days, but certain forms of expression are denigrated. It was hard for someone like Amy Clampitt to be accepted because she used very ornate vocabulary, and it was considered elitist (by some commentators) to write in the way that Amy Clampitt wrote. It was a diction perfectly natural to her since she was, among other things, a reference librarian, a bird watcher, and a much-traveled person.

INTERVIEWER

Yet her subjects were very contemporary, weren’t they, using as just one example, violence towards women?

VENDLER

Yes, but even so there was a great deal of irritation expressed against her style. Certain styles are taboo, especially in the kind of democratic ethos where poetry is supposed to be accessible and inviting. A lot of people found the ornateness of her surface repellent. I didn’t, but other people did. So I would say that certain styles may be more taboo than certain subject matters.

INTERVIEWER

Are you more interested in the lyric poem than in, say, narratives or dramatic poetry?

VENDLER

Yes, because I think in good narrative poetry or good dramatic poetry the poetry has to play a subordinate role to the principal structure that animates that genre. That is, the principal structure of narrative is some ongoing linearity; it may, like Spenser, never get to an end, but it has to appear to be heading towards an end. And the same in drama: the principle of conflict on which drama lives has to be the generating principle, and the poetry is subordinate to that generating principle. So that in the dramatic poem or the narrative poem poetry is chiefly an expressive not a structural means whereas in the lyric poem, it is a structural end.

INTERVIEWER

What, in your view, is the function of the lyric? Can it be ideological or philosophical?

VENDLER

Any statement not only can be, but probably must be, ideological, that is to say coming from some viewpoint or other. And there’s a long and noble history of philosophical poetry, from Lucretius on, that finds itself at home in a discourse it shares with some forms of philosophy—discourse about the soul or the self or about the realm of ideas. A poetry exhibiting strong ideological content—a strong religious content, a strong political content, a strong feminist content—can be just as good as any other sort of poetry. English has a lot of good religious poetry that has very strong ideological content. There is nothing in itself about a strong ideological position (think of Milton) that prohibits writing good poetry; it’s all in how it’s done.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think there’s much cross-fertilization between American poetry and that of Ireland and Eastern Europe or South America?

VENDLER

Yes, it’s one of the best things that has happened, I think, to American poetry, which originally looked almost exclusively towards English poetry. Then, with the rise of international modernism, there’s a sense of immense energy coming into Eliot from Laforgue and Mallarmé; coming into Yeats from the No drama; and coming into Pound from China and also from Italy. This kind of cross-fertilization seems to me not only very useful—think of the influence of Trakl or Neruda or Milosz on contemporary poets—but indispensable to poetry.

INTERVIEWER

You have spoken about how you wanted a mirror of your feelings in poetry. Is it fair to assume that poets who do not embody your feelings are poets you cannot write about?

VENDLER

There are certainly feelings that I may not have experienced and can’t respond to well. They might be the feelings of going out on a hunt with your grandfather, something I’ve never done. They might be feelings of a son to his father, which I believe are probably different from those that a daughter feels towards a father. There aren’t perfect overlaps in feeling among people. The poetry of war is something I find hard to respond to adequately.

INTERVIEWER

What’s the first poem you remember reading?

VENDLER

I suppose they were hymns. We sang hymns in church, and my grandfather, who had a very resonant baritone voice, was the head usher in the church. I remember him striding down the middle of the church collecting money in the offertory basket while singing whatever the offertory hymn might be. That was before I read poems. I suppose A Child’s Garden of Verses was the first poetry I remember being read to me.

INTERVIEWER

In your introduction to Soul Says you comment that “the poets about whom I have written in the essays in this book are poets whom I admire.” Yet there are rather harsh pieces on Adrienne Rich and Robinson Jeffers included. Do you not perceive them as negative reviews, or is your inclusion of these pieces an effort at endorsement in spite of the review’s negative contents?

VENDLER

What I endorse in anybody (if one can speak of such a thing as endorsement) is a style that has become recognizable among the styles of its century. I think you do pick up Adrienne Rich and think, That’s Adrienne Rich; and I think you do pick up Robinson Jeffers and think, That’s Robinson Jeffers. In my mind, that is a very high and rare and unusual achievement by any writer. Yet I also think that there are people who use their idiosyncratic style to better or to worse advantage. So if I point out something that seems to me strained or forced or incomplete about a poet, it is nonetheless said about a poet I admire.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think James Merrill’s contribution was to the last half-century of poetry?

VENDLER

Writing the best sonnets . . . he certainly did wonderful things with sonnets. A sequence like “Matinees” seems to me such an inventive poem; or his most recent one, the fifteen-line sonnets of “The Ring Cycle” in the new book, A Scattering of Salts, where he does “Matinees” over. It’s a form that he came back to all his life and seemed to find increasing amusement and pleasure within. That kind of inventiveness and fertility seems to me characteristic of what Merrill could do with all the forms in English. He never ceased to experiment with form in the most exhilarating and unexpected ways. In the last book, there’s a poem called “Self-Portrait in Tyvek™ Windbreaker” where he says “Sing our final air,” and then there’s a stanza of quasi-ottava rima full of asterisks and crossouts and mistakes. To think that your final air is something radically, formally, and even semantically incomplete, is something that only Merrill would have done.

INTERVIEWER

I think I heard that was the first poem he wrote on the computer . . . it might be that there was something about the machinery that permitted him that freedom. And what about Amy Clampitt? I mention these two, of course, because they are recently deceased.

VENDLER

I liked Amy Clampitt’s whole project. It was a project aimed at having a complete voice in a way that a lot of women poets have not aspired to. It was a voice that was interested in society and in the private life, in love and in nature, in travel and in intellectual things, in science and in family matters, in the past as well as the present. Given the restricted experience of most women in the past, it was exhilarating to see someone with as various a voice as Amy Clampitt, rather than a woman’s poetry that consisted solely of the domestic voice. And a poetry that didn’t consist solely of the protest voice, though the protest voice is very evident in Clampitt—protests against the domestic life of women; protests against government policy. But it was a voice that also loved high intellectuality and all that that implied, which the usual protest poetry doesn’t often embody.

INTERVIEWER

A handful of poets have chosen suicide. Do you have a view about suicide?

VENDLER

Well, a handful of other people have chosen suicide too. Doctors, accountants, dentists, what have you. The highest rate of suicide is among physicians, partly because they have access to drugs that make it easier to commit suicide. I don’t think that the poets’ suicides are necessarily consequent upon their having had the disposition or the talent to write poetry. On the contrary, as many people have said, it was probably their poetry that kept them alive and kept them from committing suicide earlier. Creative effort is such a passionate process in itself, it’s a way out of depression rather than into it.

INTERVIEWER

I know you’re not a practicing Catholic; does that mean that you don’t believe in an afterlife?

VENDLER

I don’t believe in anything of that sort.

INTERVIEWER

Meaning you’re an atheist?

VENDLER

Yes.

INTERVIEWER

But don’t you believe in the existence of souls?

VENDLER

Only so long as they have bodies. I do believe we are something other than our corpses, but what we are is a functioning biological mechanism. And when the biological conjunctions stop, then the mechanism can’t work anymore. We have a very highly organized nervous system, which when it works well is something that we refer to as the soul.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that your soul is happy in your body?

VENDLER

Well, no. Is anybody’s soul happy in his body? Think of Marvell’s witty poem, taking off on St. Paul’s protest by the soul, “Who shall deliver me from the body of this death?” Marvell’s body replies, “O who shall me deliver whole / From bonds of this Tyrannic Soul?” Body and soul have rarely got on well.

INTERVIEWER

I remember your once saying that you had an Irish peasant body. Do you still feel that way?

VENDLER

Yes, I do. I see it in myself and in my father, whose body I’ve inherited: a stocky body with stamina and a certain peasant drive, maybe.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever not been able to write?

VENDLER

Yes, when I was ill and had entered a period of great exhaustion where I simply didn’t have the mental energy to write.

INTERVIEWER

Do you work daily? What is your routine?

VENDLER

No, I have no routine. I hate routines. I have no fixed hours for sleeping, eating, waking, working.

INTERVIEWER

Do you write at a desk or in bed or on a sofa?

VENDLER

I write in various places . . . sometimes on the sofa, sometimes in bed, sometimes sitting at the computer. I hate routine more than anything else. I’m a night person, so I tend to write later in the day rather than earlier, but I have no fixed hours and no fixed days.

INTERVIEWER

How did you begin to review for The New Yorker?

VENDLER

Well, I had done reviewing for The New York Times for some years, then Mr. Shawn phoned me up and asked if I’d like to write about poetry for The New Yorker, and I said yes. That was in 1978.

INTERVIEWER

Had he read a particular piece?

VENDLER

He didn’t say. I suspect it was Howard Moss who probably had been following my writing in the Times and who suggested me to Mr. Shawn.

INTERVIEWER

At sixty-three you show no sign of slowing down. Do you feel that you have slowed down?

VENDLER

What I mind more than slowing down, which everyone has done by sixty-three, is that in a day you no longer have a third wind and sometimes you don’t even have a second wind. I always had a third wind for many years, and then I always had a second wind. Now, if I’ve had a hard day, I don’t feel disposed to write at night. What I miss more is the inevitable sense of distance from younger poets. You always know the poets of the generation ahead of you, and also of your own generation, the companions of your journey through life. You also tend to know, I think, the poets of one generation down, that is to say fifteen to twenty years younger than yourself. They’re pretty close to you too. But then you lose touch. I would be surprised if there were a critic who was in touch at the age of sixty-three with what was going on with the twenty-four year olds.

INTERVIEWER

Have you been happy with your vocation?

VENDLER

Well, since I can’t imagine any other . . . well, no, I can imagine one other. I do have a fantasy life in medicine. There are some versions of medicine that I could have practiced with some enjoyment, especially the ones that require complicated diagnoses. If you’re a doctor, you certainly don’t have time to write, and that’s what turned me away from medicine. I realized that I was spending my time in the library stacks of poetry, not of science.

INTERVIEWER

I understand you’re just completing a book about Shakespeare’s sonnets. Might one say that you’ve come to Shakespeare by way of Stevens and Keats? If so, where will you go next?

VENDLER

Shakespeare has always been there. I memorized so many of Shakespeare’s sonnets when I was fifteen that when I later came to Keats and Stevens it was Shakespeare that I saw in them. They all interpenetrate by the time you know them all.

Where I’ll go next, I don’t know. I have a deep wish to write on Milton, but that would take a long time because I’d have to make myself into a Miltonist first. I’d also like to write a book on Yeats’s lyric styles, because most of the work on Yeats has been animated by biography more than by poetry.

INTERVIEWER

How is your study of the Shakespeare sonnets different from others? I gather you do not read with the usual social or cultural or moral agenda.

VENDLER

During the nineteenth century, the study of Shakespeare’s sonnets was governed by a biographical agenda. Later, it was also governed by the “universal wisdom” agenda: the sonnets have been mined for the wisdom of friendship, the wisdom of the acquiescence to time, the wisdom of love. But I’m more interested in them as poems that work. They seem to me to work awfully well (though not everyone thinks so). And each one seems to work differently. Shakespeare was the most easily bored writer that ever lived, and once he had made a sonnet prove out in one way, he began to do something even more ingenious with the next sonnet. It was a kind of task that he set himself: within an invariant form, to do something different—structurally, lexically, rhythmically—in each poem. I thought each one deserved a little commentary of its own, so I’ve written a miniessay on each one of the one hundred and fifty four.

INTERVIEWER

How does American poetry look to you at the end of the twentieth century? Are you hopeful for the next?

VENDLER

I don’t think poetry is killable. At one point, Ezra Pound wrote sardonically of “the filthy . . . unkillable infants of the very poor.” And I think of poetry as one of those. It will keep cropping up no matter what is done with it, because human beings feel such a perennial impulse to play with language. It’s like any other kind of play . . . play with notes, play with colors, play with line, play with rhythm. The human impulse to play with a given medium seems to be ineradicable.

INTERVIEWER

“Is criticism a true thing?” Keats asked. What would be your reply?

VENDLER

It can never be true for the poet because what the poet has said, he has already said, and therefore criticism seems either deflective or odious. But for the critic, criticism is a form of natural self-expression, as poetry is to the poet. So, for a critic, criticism is a true thing. Criticism isn’t written for poets, it’s written for other readers. One hopes it is true for other readers if it’s true for oneself.