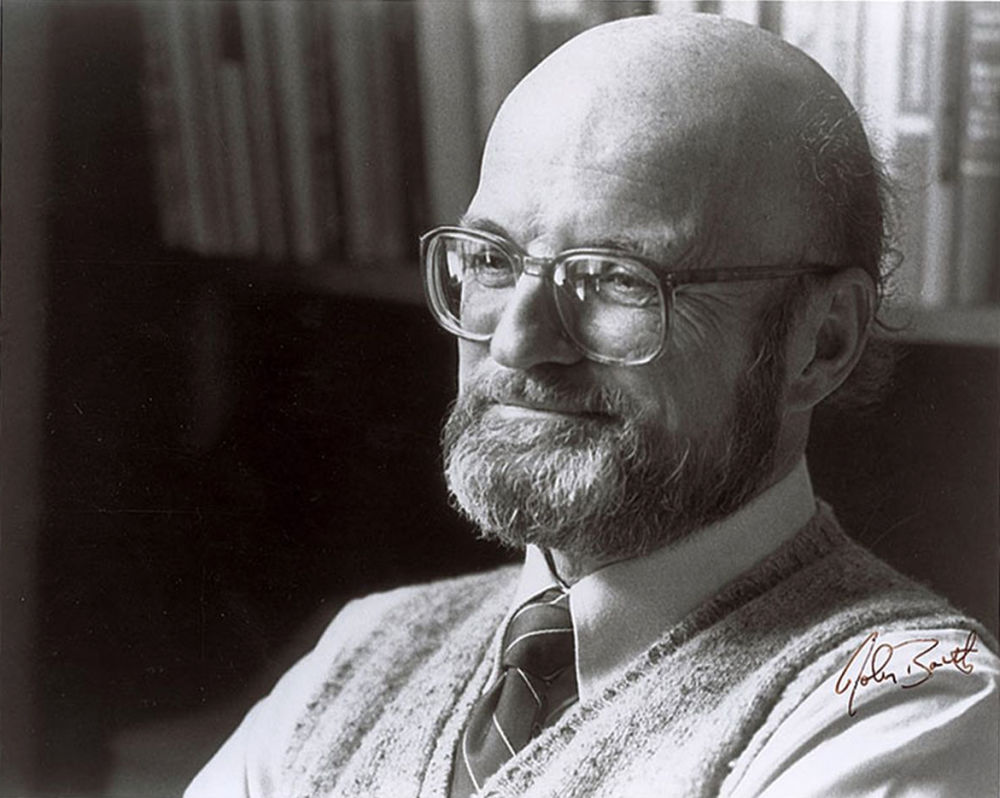

Issue 122, Spring 1992

Claude Simon, ca. 1967.

Claude Simon, ca. 1967.

Claude Simon has long denied that he writes his novels in the style of the French nouveau roman—in fact he considers nouveau roman to be a misleading term under which critics have falsely grouped the work of several French authors, including Nathalie Sarraute, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and Marguerite Duras, whose literary styles, themes, and interests are, according to Simon, quite diverse. But it was nevertheless as a “new novelist” that Simon was known best until he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1985. Literary critics and academicians have attributed to him everything from an obsession with the philosophy of the absurd to a penchant for nihilism. The symbolism in his work has been extensively analyzed, excessively so in the eyes of Simon—he rejects almost all interpretation of his work, portraying himself as a straightforward writer who draws on the material that life provides him. What emerges, though, is challenging, baroque. Sentences continue for pages; passages contain no punctuation. Always, he is lyrical. More often than not, Simon depicts a reality of death and dissolution, with war a common presence. He rejects the conventional novels of the nineteenth century and embraces Dostoyevsky, Conrad, Joyce, Proust, and Faulkner, whose highly charged, evocative use of language he draws upon. Objects and scenes echo each other, are repeated, turned over and examined in minute detail from many angles; time flows backward, forward, and back again with changing points of view.

Claude Simon was born in 1913 in Tananarive, Madagascar and raised in Perpignan, France. His father died in battle when Simon was less than a year old. Orphaned at age eleven, he was sent to boarding school in Paris, but spent summers with relatives. As a young man, he briefly studied painting and traveled to Spain during the civil war there, where he sided with the Republicans. He once said that he turned to writing because he imagined it would be easier than either painting or revolution. Simon began his literary career on the eve of World War II with the novel Le Tricheur, but was conscripted into the military before he could complete the manuscript. He narrowly survived his tour of duty with an anachronistically outfitted squadron of the French cavalry, which faced German panzers on horseback, armed with sabers and rifles. Le Tricheur was finally published in 1945. Simon had received an inheritance, and at the close of the war, was able to devote himself entirely to writing.

His works have been widely translated, ten of them into English, including the novels The Grass (1960), The Flanders Road (1961), The Palace (1963), Histoire (1968), Conducting Bodies (1974), Triptych (1976), Georgics (1989), The Invitation (1991), and The Acacia (1991).

Simon now lives in Paris, where he has spent most of his adult life. He summers in the south of France, near the town of Perpignan where he grew up. This interview was conducted primarily by mail, during the spring and summer of 1990. A brief final session was held in the bright and spacious living room of Simon’s modestly furnished Paris apartment, an airy fifth-floor walk-up in the fifth arrondissement. The white walls were hung with artwork; the environment bore little resemblance to the dark world Simon depicts in his fiction.

INTERVIEWER

Would you describe yours as a happy childhood?

CLAUDE SIMON

My father was killed in the war, in August of 1914, and my mother died when I was eleven years old, after which I was sent, as a boarding student, to a religious institution with very severe discipline. Although I was orphaned at a young age, I regard my childhood as having been rather happy—thanks to the affection that my uncles and aunts and cousins showered on me.

INTERVIEWER

What was the name of the boarding school?

SIMON

Stanislas College, which is actually a grammar school in Paris. My mother was very pious and had wanted me to receive a religious education.

INTERVIEWER

Did this institution have any effect on you emotionally or intellectually?

SIMON

I became an atheist. That, it seems to me, is evident in my books.

INTERVIEWER

How did your formal education shape you?

SIMON

I received what one would call a cultural base—Latin, mathematics, sciences, history, geography, literature, foreign language. A huge defect in secondary instruction in France is that one practically never speaks of art—music, painting, sculpture, architecture. For instance, I was made to learn hundreds of verses by Corneille, but one never spoke of Nicolas Poussin, who is much more important.

INTERVIEWER

You fought alongside the Republicans in the Spanish civil war, but became disillusioned and left the cause. Why?

SIMON

I did not fight. I arrived in Barcelona in September 1936 “trying to be a spectator more than an actor in the comedies that play in the world.” That’s one of the principles set forth by Descartes. When he wrote that, the word comédie designated every theatrical representation, comic as well as tragic. For Descartes, who lived austerely observing the weakness of human passions, this word had a slightly pejorative and ironic sense. Balzac also used the word in the title of a group of books, La Comédie humaine, that is actually given up to tragic episodes. The most woeful ingredients of the Spanish civil war were its selfish motives, the hidden ambitions it served, the emphasis on hollow words used by both sides; it seemed to be a comedy—terribly bloody—but a comedy all the same. Still, given the degree to which the war was murderous and involved a great deal of treachery, I could not myself qualify it as a comédie. What drew me there? Naturally, my sympathy for the Republicans; but also my curiosity to observe a civil war, see what was happening.

INTERVIEWER

Your life has been touched a great deal by luck: You were one of the few French cavalrymen to survive the Battle of the Meuse in 1940, which took place on the field where your father died. Taken prisoner by the Germans, you escaped after six months and then worked in the resistance. After this period you retired to your family’s country estate, where an inheritance has enabled you to devote yourself exclusively to your writing.

SIMON

All my life I have been favored by incredible luck. It would take too long to enumerate all of the occasions, though one example stands out among all the others: In May 1940, my squadron was ambushed by German tanks. Under fire, the foolish order was given to “fight on foot,” followed almost immediately by the order, “on horseback, at a gallop!” Just as I put my foot in the stirrup, the saddle slipped. Just my luck, I thought, in the middle of the battle! But that’s what saved me: On foot, I found myself in a dead zone, a level crossing where I couldn’t be hit. The majority of those who had remounted were killed. I could tell you about ten or twelve occasions when I had similarly good luck. Often, as in the case of the ambush, what one thinks is bad luck turns out to be the opposite. Paul Valéry wrote: “When everything is added up, our life is nothing but a series of hazards to which we give responses more or less appropriate.”

INTERVIEWER

How did you escape the German prison camp?

SIMON

I managed to get onto a train of prisoners the Germans were bringing to Frontstalag for the winter. The camp was badly guarded. Just after I arrived, I escaped in broad daylight by slipping between two German sentinels into the forest. From there, hiding along the way, I reached the line of demarcation.