Issue 8, Spring 1955

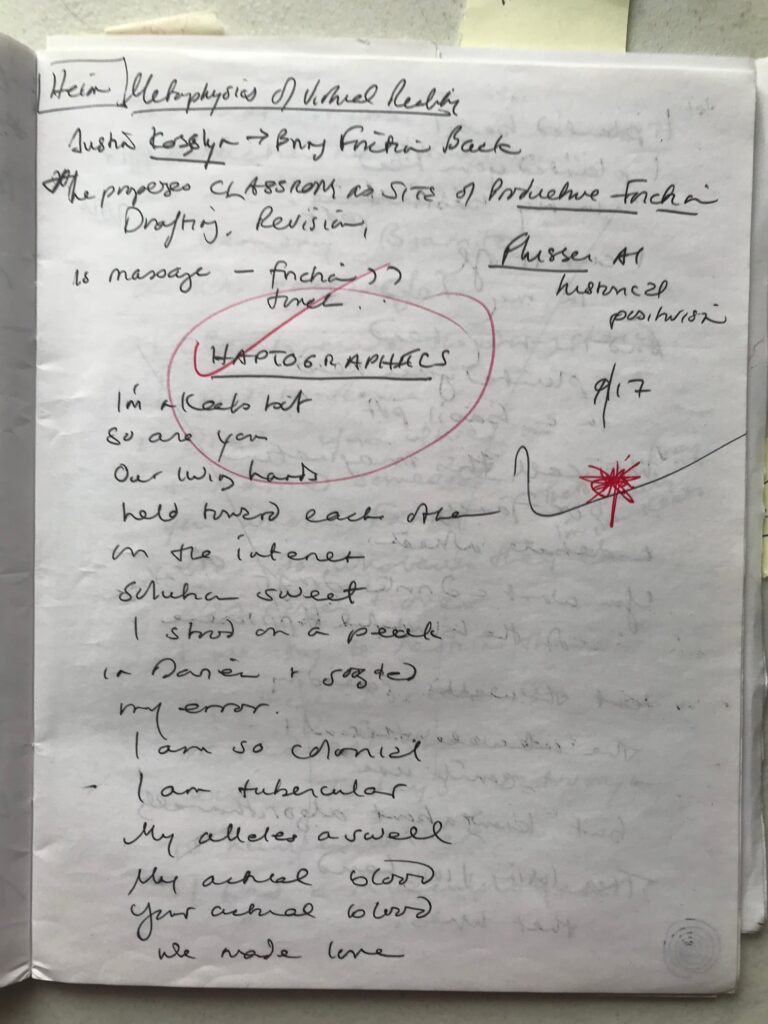

Ralph Ellison, 1955. Illustration by Rosalie Seidler.

When Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison’s first novel, received the National Book Award for 1953, the author in his acceptance speech noted with dismay and gratification the conferring of the award to what he called an “attempt at a major novel.” His gratification was understandable, so too his dismay when one considers the amount of objectivity Mr. Ellison can display toward his own work. He felt the state of United States fiction to be so unhappy that it was an “attempt” rather than an achievement which received the important award.

Many of us will disagree with Mr. Ellison’s evaluation of his own work. Its crackling, brilliant, sometimes wild, but always controlled prose warrants this; so does the care and logic with which its form is revealed, and not least its theme: that of a young negro who emerges from the South and—in the tradition of James’s Hyacinth Robinson and Stendhal’s Julien Sorel—moves into the adventure of life at large.

In the summer of 1954, Mr. Ellison came abroad to travel and lecture. His visit ended in Paris where for a very few weeks he mingled with the American expatriate group to whom his work was known and of much interest. The day before he left he talked to us in the Café de la Mairie du Vie about art and the novel.

Ralph Ellison takes both art and the novel seriously. And the Café de la Mairie has a tradition of seriousness behind it, for here was written Djuna Barnes’s spectacular novel, Nightwood. There is a tradition, too, of speech and eloquence, for Miss Barnes’s hero, Dr. O’Connor, often drew a crowd of listeners to his mighty rhetoric. So here gravity is in the air, and rhetoric too. While Mr. Ellison speaks, he rarely pauses, and although the strain of organizing his thought is sometimes evident, his phraseology and the quiet, steady flow and development of ideas are overwhelming. To listen to him is rather like sitting in the back of a huge hall and feeling the lecturer’s faraway eyes staring directly into your own. The highly emphatic, almost professorial intonations, startle with their distance, self-confidence, and warm undertones of humor.

RALPH ELLISON

Let me say right now that my book is not an autobiographical work.

INTERVIEWERS

You weren’t thrown out of school like the boy in your novel?

ELLISON

No. Though, like him, I went from one job to another.

INTERVIEWERS

Why did you give up music and begin writing?

ELLISON

I didn’t give up music, but I became interested in writing through incessant reading. In 1935 I discovered Eliot’s The Waste Land, which moved and intrigued me but defied my powers of analysis—such as they were—and I wondered why I had never read anything of equal intensity and sensibility by an American Negro writer. Later on, in New York, I read a poem by Richard Wright, who, as luck would have it, came to town the next week. He was editing a magazine called New Challenge and asked me to try a book review of Waters E. Turpin’s These Low Grounds. On the basis of this review, Wright suggested that I try a short story, which I did. I tried to use my knowledge of riding freight trains. He liked the story well enough to accept it, and it got as far as the galley proofs when it was bumped from the issue because there was too much material. Just after that the magazine failed.

INTERVIEWERS

But you went on writing—

ELLISON

With difficulty, because this was the recession of 1937. I went to Dayton, Ohio, where my brother and I hunted and sold game to earn a living. At night I practiced writing and studied Joyce, Dostoyevsky, Stein, and Hemingway. Especially Hemingway; I read him to learn his sentence structure and how to organize a story. I guess many young writers were doing this, but I also used his description of hunting when I went into the fields the next day. I had been hunting since I was eleven, but no one had broken down the process of wing-shooting for me, and it was from reading Hemingway that I learned to lead a bird. When he describes something in print, believe him; believe him even when he describes the process of art in terms of baseball or boxing; he’s been there.

INTERVIEWERS

Were you affected by the social realism of the period?

ELLISON

I was seeking to learn and social realism was a highly regarded theory, though I didn’t think too much of the so-called proletarian fiction even when I was most impressed by Marxism. I was intrigued by Malraux, who at that time was being claimed by the Communists. I noticed, however, that whenever the heroes of Man’s Fate regarded their condition during moments of heightened self-consciousness, their thinking was something other than Marxist. Actually they were more profoundly intellectual than their real-life counterparts. Of course, Malraux was more of a humanist than most of the Marxist writers of that period—and also much more of an artist. He was the artist-revolutionary rather than a politician when he wrote Man’s Fate, and the book lives not because of a political position embraced at the time but because of its larger concern with the tragic struggle of humanity. Most of the social realists of the period were concerned less with tragedy than with injustice. I wasn’t, and am not, primarily concerned with injustice, but with art.

INTERVIEWERS

Then you consider your novel a purely literary work as opposed to one in the tradition of social protest.

ELLISON

Now, mind, I recognize no dichotomy between art and protest. Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground is, among other things, a protest against the limitations of nineteenth-century rationalism; Don Quixote, Man’s Fate, Oedipus Rex, The Trial—all these embody protest, even against the limitation of human life itself. If social protest is antithetical to art, what then shall we make of Goya, Dickens, and Twain? One hears a lot of complaints about the so-called protest novel, especially when written by Negroes, but it seems to me that the critics could more accurately complain about the lack of craftsmanship and the provincialism which is typical of such works.

INTERVIEWERS

But isn’t it going to be difficult for the Negro writer to escape provincialism when his literature is concerned with a minority?

ELLISON

All novels are about certain minorities: the individual is a minority. The universal in the novel—and isn’t that what we’re all clamoring for these days?—is reached only through the depiction of the specific man in a specific circumstance.