Issue 94, Winter 1984

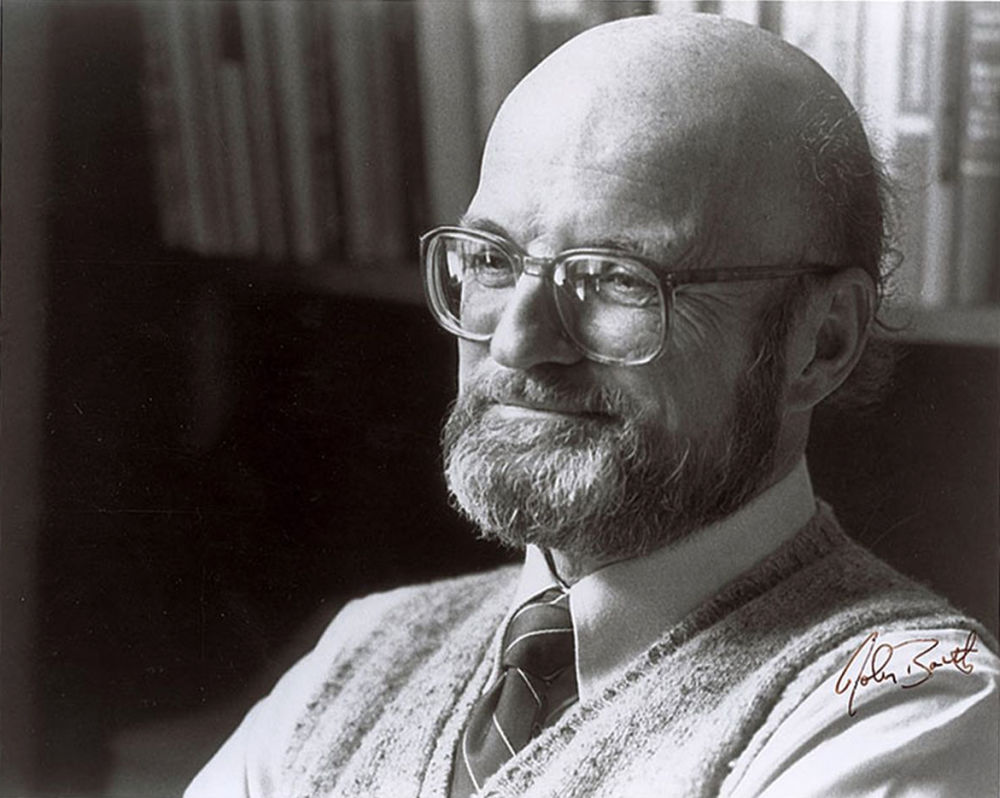

Photograph by K. Kelly Wise.

Photograph by K. Kelly Wise.

Robert Fitzgerald met us in his office in Harvard’s Pusey Library one morning in August 1983. The day was muggy; Fitzgerald was wearing a blue seersucker suit and a sport shirt. He carried a worn book bag over his shoulder, announcing, “I’ve brought some exhibits!”

Pusey Library is a new building and Fitzgerald’s office is a small, durably carpeted room, somewhat longer than it is wide. A bookshelf hangs over a desk. In the room there’s just enough space for an easy chair and a straight chair. Standing at the door, we could see out a narrow window at the opposite end of the room onto a courtyard, where grass and a few thin trees were trying to grow. Fitzgerald shook an old, pocket-sized copy of Virgil out of his bag onto his desk. We sat down, and the interview began.

Fitzgerald speaks slowly and very deliberately. When he finds a quotation or phrase or word that seems particularly telling, he marks the occasion with a small click of the tongue. We talked for about an hour and a half, and then went to lunch.

INTERVIEWER

First, we thought we’d ask you what made you want to be a writer?

ROBERT FITZGERALD

I don’t think it comes on that way . . . wanting to be a writer. You find yourself at a certain point making something in writing, and this seems to be great fun. I guess in high school—this was in Springfield, Illinois—I discovered that I could put words together and the results were pleasing to me. After I had discovered the charms of verse, I wrote verse all the time. Then when I was a senior, a great, kinetic teacher named Elizabeth Graham conducted something called the Scribbler’s Club for a few seniors. It was a class, but it called itself a club, and was engaged in writing throughout the year. They put out a little magazine. I guess that was when the whole thing came to a head. I wrote a lot of verse and prose. So it wasn’t so much wanting to be a writer as having a knack or fondness for putting things into verse.

INTERVIEWER

Were there any writers whose work you particularly admired at that time?

FITZGERALD

Well, I was greatly taken by a story called “Fifty Grand” in Scribner’s Magazine, which came into the Scribbler’s Club. I thought it was really wonderful. That was Ernest Hemingway’s story about the boxer who’s offered $50,000 to throw a fight and, though double-crossed and fouled, still goes on to throw it. It’s a faultless story. I was also greatly taken at that time by Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop. And in verse, well, you know, you come across the work of William Butler Yeats at a certain point and your head endures fraction.

INTERVIEWER

Where did you go when you left Springfield?

FITZGERALD

I went to the Choate School in Wallingford, Connecticut. When I got out of high school in Springfield, Illinois, in 1928, I had applied for and had been admitted to Yale. My family felt that since I was only seventeen, it would be a little premature to put me in college. So, I went to Choate for a year. While at Choate, I met Dudley Fitts, who was one of the masters there. He had been at Harvard, and I got the idea that where Fitts had gone to college was the place for me to go.

INTERVIEWER

What sort of influence did Fitts have on you?

FITZGERALD

He encouraged me to learn Greek. I would never have gone in for it unless he had dropped the word that it was nice to know a little Greek. So when I got to Harvard, I enrolled in a beginning course. And Fitts was up on Pound and Eliot and Joyce. He read me The Waste Land, which changed my life.

INTERVIEWER

Your early poems are full of dislocated, unidentified speakers, images of night and darkness, glinting lights. What drew you to such imagery?

FITZGERALD

I think that the life of the undergraduate, now and certainly in those days, was nocturnal, quite a lot of it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you still feel close to those poems?

FITZGERALD

I recognize them as my own and I don’t disown them or feel silly about them. I think some of them are still pretty good, for what they are. I wouldn’t have put them in my collection unless I thought they were worth including.

INTERVIEWER

One of your poems, “Portraits,” is a portrait of John Wheelwright. How did you get to know him?

FITZGERALD

It must have been Fitts who introduced me to Wheelwright, and also to Sherry Mangan, a very spectacular literary figure. Both of these gents were socialists and political thinkers. Eventually, Sherry Mangan, whose early poetry was highly stylized and affected, settled into a life of dedication to the Trotskyite cause: socialism without the horrors of Stalinism. Wheelwright, too, was of this persuasion. Well, you probably know something of Wheelwright’s place among the eccentrics of Boston of his time. He was always in his great big raccoon-skin coat and he belonged to the best Boston society of the time. Yet after an evening with friends, wherever the Brahmins of the time congregated, he would go out and do a soapbox turn on the Common, lecturing the cause of socialism in his tux and so on. He was also a devout Anglo-Catholic. These figures, along with B. F. Skinner, who was the white-haired boy of psychology around here at that time, and a physicist named Cuthbert Daniel, were all intellectuals of considerable—what?—presence and audacity and interest. None of them had any money and at that time—this was ’32, ’33—this country had already felt the very cold grip of the Depression. The mystery of what in the world was going on to deprive people of jobs and prospects, and of what was the matter with American society, occupied these guys constantly. I remember that my senior year I went in to see my tutor and I found this man, a tutor in English, reading Das Kapital. When I noticed it, he said, “Yes. I don’t intend to spend my life taking care of a sick cat”—by which he meant capitalist society.

INTERVIEWER

Were you sympathetic to revolutionary causes too?

FITZGERALD

Not very, although I had to realize that something was going on. It had been taken for granted in my family that I would go to law school after college. It turned out that the wherewithal to go to law school had vanished, so I had to go to work. I went to work on a New York newspaper, The Herald Tribune. But I could never get passionate about revolution, at that time or later—it was a passion that was denied me.