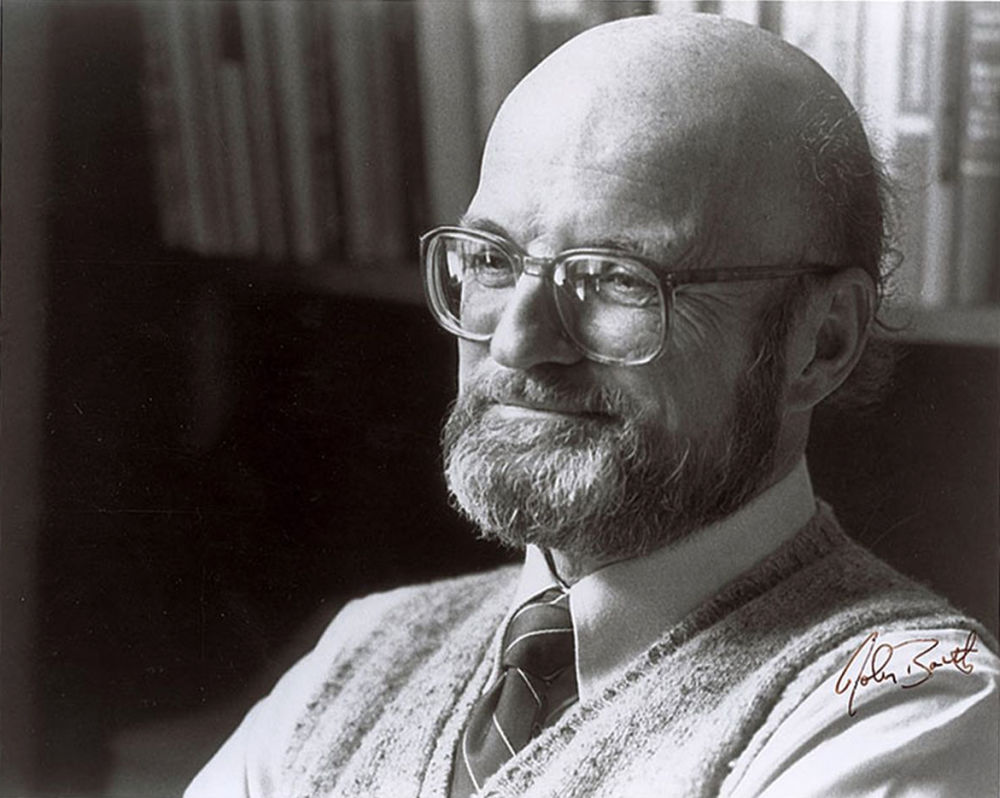

Issue 237, Summer 2021

Photo courtesy of Mayank Austen Soofi

Photo courtesy of Mayank Austen Soofi

After her first novel, The God of Small Things (1997), Arundhati Roy did not publish another for twenty years, when The Ministry of Utmost Happiness was released in 2017. The intervening decades were nonetheless filled with writing: essays on dams, displacement, and democracy, which appeared in newspapers and magazines such as Outlook, Frontline, and the Guardian, and were collected in volumes that quickly came to outnumber the novels. Most of these essays were compiled in 2019 in My Seditious Heart, which, with footnotes, comes to nearly a thousand pages; less than a year later she published nine new essays in Azadi.

To see that two-decade period as a gap, or the nonfiction as separate from the fiction, would be to misunderstand Roy’s project; when finding herself described as “what is known in twenty-first-century vernacular as a ‘writer-activist,’ ” she confessed that term made her flinch (and feel “like a sofa-bed”). The essays exist between the novels not as a wall but as a bridge. Roy’s subject and obsession is, throughout, power: who has it (and why), how it is used (and abused), the ways in which those with little power turn on those with less—and, importantly, how to find beauty and joy amid these struggles. The God of Small Things is a novel focused on one family, while The Ministry of Utmost Happiness has a larger scale, but in the questions they ask and the themes they explore, both novels are as “political” as any of her essays. Her essays, in turn, are as powerfully and lovingly written as her fiction, with the same suspicion of purity, perfection, and simple stories.

Roy was born in 1959 in Shillong, in India’s northeast, and grew up mostly in Kerala, on the southwestern coast. She left home in 1976 to attend the School of Planning and Architecture in New Delhi and has lived in the capital ever since, without practicing architecture. (She brought the school and its patois to vivid life in the movie In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones, which she told me is now screened there every year for the incoming class.) She has received numerous honors, including the 1997 Booker Prize for The God of Small Things, the Lannan Cultural Freedom Award, the Sydney Peace Prize, the Norman Mailer Prize for Distinguished Writing, and a 2017 Mahmoud Darwish Award, but might take even more pride in the list of those who have found her a thorn in their side. She told me that at a panel at the World Water Forum in 2000, after an executive promoting the privatization of water systems introduced himself by saying he wrote about water “because I’m paid to,” she began by saying, “My name is Arundhati, and I write about water because I’d be paid a great deal not to.”

We conducted this interview over three mornings in Chicago in the fall of 2019 as Roy was visiting the U.S. for speaking engagements. In private, she projects the same passion and urgency as she does in public, but there is a greater opportunity to appreciate her sense of humor as well—a generous one, which seeks always to share what she sees with her interlocutor.

INTERVIEWER

Can you tell me a bit about your reading habits?

ARUNDHATI ROY

When I was growing up in Kerala, to nourish the English part of my brain—there was a Malayalam part, too—there was a lot of Shakespeare and a lot of Kipling, a combination of the most beautiful, lyrical language and some very unlyrical politics, although I didn’t see it that way then . . . I was definitely influenced by them, as I have been later by James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, John Berger, Joyce, Nabokov. What an impossible task it is to list the writers one loves and admires. I’m grateful for the lessons one learns from great writers, but also from imperialists, sexists, friends, lovers, oppressors, revolutionaries—everybody. Everybody has something to teach a writer. My reading can switch rather oddly from Mrs. Dalloway to a report about the National Register of Citizens and the two million people in Assam who have been struck off it and have suddenly ceased to be Indian citizens. Ceased to have any rights whatsoever.

A novel that overwhelmed me recently is Life and Fate by Vasily Grossman. Just incredible—the audacity, the range of characters and situations. It begins with a surreal description of the Volga burning—the gasoline floating on the surface of the water catching fire, giving the illusion of a burning river—as the battle for Stalingrad rages. The manuscript was arrested by the Soviet authorities, as though it were a person. Another recent read was The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, by Giorgio Bassani. It’s about the time just before World War II, when many Jews in Italy were members of the Fascist Party. The Finzi-Continis are an elite Jewish family who live in a mansion with huge grounds and tennis courts. The book is centered around a love affair between the daughter of the Finzi-Continis and a person who is an outsider to that world as the Holocaust closes in. There is something about the unchanging stillness of that compound, the refusal to acknowledge what is happening, even while the darkness deepens around it. It is chilling and so eerily contemporary. All of the entitled Finzi-Continis end up dead. Considering what happened in Stalinist Russia, what happened in Europe during World War II—one is reading, searching for ways to understand the present. What fascinates me is how some of the people who were shot by Stalin’s firing squads died shouting “Long live Stalin!” People who labored in the gulag camps wept when he died. Ordinary Germans never rose up against Hitler, even as he persisted with a war that turned their cities into rubble. I look for clues to human psychology in Ian Kershaw’s biography of Hitler, in the memoirs of Nadezhda Mandelstam, wife of the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, whom Stalin basically killed, in the poems of Anna Akhmatova and Kolyma Tales by Varlam Shalamov.

INTERVIEWER

A lot of Russians.

ROY

[laughs] A lot of Russians, right now, yes. There is something so juicy about the way they could take on a big narrative. And, of course, Chekhov, who can do it in that microscopic way, too. I enjoy the way they refuse to stay in their lanes. Especially now that the traffic regulations are getting stricter, the lanes are getting narrower and more constricted. Everybody, writers, readers, public conversation in general is being straitjacketed. Controlled from every direction, up, down, and sideways. In India, cultural censorship is literally meted out by mobs on streets, mostly with tacit blessings from the government. We seem to be approaching a kind of intellectual gridlock.

INTERVIEWER

Your writing hasn’t really ever been tempted to go into the microscopic, short story mold—the novel seems like the form you chose.

ROY

I love immersing myself in the universe of a novel for years. There is never a time when I am more alive. Some writers suffer through that process, but I enjoy it. Being in that universe, that imperfect universe, is like being in prayer—it is separate from the product or the end or the success or the nonsuccess of the product. What a horrible word for a novel—product. My apologies.

INTERVIEWER

What is that product? What is a novel supposed to be?

ROY

I think there is an increasing danger of novels becoming too streamlined, domesticated. When you read Vasily Grossman or the big Russian novels, they are wild and unwieldy, but now there’s a way in which literature is being commodified and packaged—is it romance, is it a thriller? Commercial? Literary? What shelf should we put it on? And now we have the phenomenon of the M.F.A. novel, which can often be a beautifully confected product. There are no rough edges. The number of characters, the length of chapters, it’s all skillfully orchestrated—and I’ll say that male novelists are allowed leeway there. They’re more easily allowed the big canvas. But with a woman, it’s like, How many characters are there in that book? Isn’t it a bit too political? I’d ask them, How many characters are there in One Hundred Years of Solitude or War and Peace or whatever? I sometimes feel that the settled classes, the contemporary cultural czars who are the arbiters of taste in the arts and in literature, are often wary of the real, deep, unsettling politics that are not part of accepted pedagogy—we are expected to write within a sort of default worldview, in which the ideas of what constitutes progress, enlightenment, and civilization are agreed upon. But I think that is changing now. It’s being challenged by young writers and poets, challenged from many directions, from across the world.