Over the past few decades, in Tennessee, archaeologists have unearthed an elaborate cave-art tradition thousands of years old. The pictures are found in dark-zone sites—places where the Native American people who made the artwork did so at personal risk, crawling meters or, in some cases, miles underground with cane torches—as opposed to sites in the “twilight zone,” speleologists’ jargon for the stretch, just beyond the entry chamber, which is exposed to diffuse sunlight. A pair of local hobby cavers, friends who worked for the U. S. Forest Service, found the first of these sites in 1979. They’d been exploring an old root cellar and wriggled up into a higher passage. The walls were covered in a thin layer of clay sediment left there during long-ago floods and maintained by the cave’s unchanging temperature and humidity. The stuff was still soft. It looked at first as though someone had finger-painted all over, maybe a child—the men debated even saying anything. But the older of them was a student of local history. He knew some of those images from looking at drawings of pots and shell ornaments that emerged from the fields around there: bird men, a dancing warrior figure, a snake with horns. Here were naturalistic animals, too: an owl and turtle. Some of the pictures seemed to have been first made and then ritually mutilated in some way, stabbed or beaten with a stick.

That was the discovery of Mud Glyph Cave, which was reported all over the world and spawned a book and a National Geographic article. No one knew quite what to make of it at the time. The cave’s “closest parallel,” reported the Christian Science Monitor, “may be caves in the south of France which contain Ice Age art.” A team of scholars converged on the site.

The glyphs, they determined—by carbon-dating charcoal from half-burned slivers of cane—were roughly eight hundred years old and belonged to the Mississippian people, ancestors to many of today’s Southeastern and Midwestern tribes. The imagery was classic Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC), meaning it belonged to the vast but still dimly understood religious outbreak that swept the Eastern part of North America around 1200 a.d. We know something about the art from that period, having seen all the objects taken from graves by looters and archaeologists over the years: effigy bowls and pipes and spooky-eyed, kneeling stone idols; carved gorgets worn by the elite. But these underground paintings were something new, an unknown mode of Mississippian cultural activity. The cave’s perpetually damp walls had preserved, in the words of an iconographer who visited the site, an “artistic tradition which has left us few other traces.”

That was written twenty-five years ago, and today there are more than seventy known dark-zone cave sites east of the Mississippi, with new ones turning up every year. A handful of the sites contain only some markings or cross-hatching (lusus Indorum was the antiquarian’s term: the Indians’ whimsy), but others are quite elaborate, much more so than Mud Glyph. Several are older, too. One of them, the oldest so far, was created around 4,000 b.c. The sites range from Missouri to Virginia, and from Wisconsin to Florida, but the bulk lie in Middle Tennessee. Of those, the greater number are on the Cumberland Plateau, which runs at a southwest slant down the eastern part of the state, like a great wall dividing the Appalachians from the interior.

That’s what it was, for white settlers who wanted to cross it in wagons. If you read about Daniel Boone and the Cumberland Gap, and how excited everyone got in the eighteenth century to have found a natural pass (known, incidentally, to every self-respecting Indian guide) through “the Cumberland Mountains,” those writers mean the Plateau. Technically, it’s not a mountain or a mountain chain, though it can look mountainous. A mountain is when you smash two tectonic plates together and the leading edges rise up into the sky like sumo wrestlers lifting up from the mat. A plateau, on the other hand, sits above the landscape because it has remained in place while everything else washed away. On the high plain of the Cumberland Plateau lies an exposed horizontal layer of erosion-resistant bedrock, a “conglomerate” (or pebbly) sandstone, which keeps the layers directly underneath from dissolving and flowing into the rivers, or at least holds back the process. It can do only so much. Fly above the Plateau in a small plane, and you can see that it’s a huge disintegrating block, calving house-size boulders as it’s inwardly shattered by seasonal “frost-wedging” or carved away by streams that crash down through the porous strata. Water bursts from steep bluff faces: the sides of a plateau don’t slope like a mountain’s do, they sheer away or tumble down at the edges. Those cliffs create a physical barrier for species, meaning you get different animals and vegetation on top and at the bottom. The German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt called that a requirement for a true plateau, this eco-segregation (Humboldt liked to chide his colleagues for playing fast and loose with the term plateau).

The Cumberland is a special kind of plateau; it’s a karst plateau, and karst means caves. Really it means cave country, or what you get when there’s plenty of exposed limestone and rain. The name karst is derived from that of another plateau, the Kras in Slovenia. There geologists made the first studies of what they termed Karstphänomen, the unique and in some cases bizarre hydrologic features associated with karstic terrain: sinkholes, blind- or pocket-valleys, coves, and subterranean lakes. Among the most famous Karstphänomen is the so-called disappearing stream. You have a big rushing stream that runs along for a million years, then suddenly a hole is dissolved in its limestone bed, and the entire flow goes underground, into a cave system, never to return. It can happen in an instant: people have watched it happen. A classic disappeared stream, all but a ghost-river, can be seen on the Cumberland Plateau; its eternally dry bed winds on through the forest like a white-cobbled highway.

The Plateau is positively worm-eaten with caves. Pit caves, dome caves, big wide tourist caves, and caves that are just little cracks running back into the stone for a hundred feet—not even a decade ago, explorers announced the discovery of Rumbling Falls Cave, a fifteen-mile (so far) system that includes a two-hundred-foot vertical drop and leads to a chamber they call the Rumble Room, in which you could build a small housing project. All of that is inside the Plateau and in the limestone that skirts its edges.

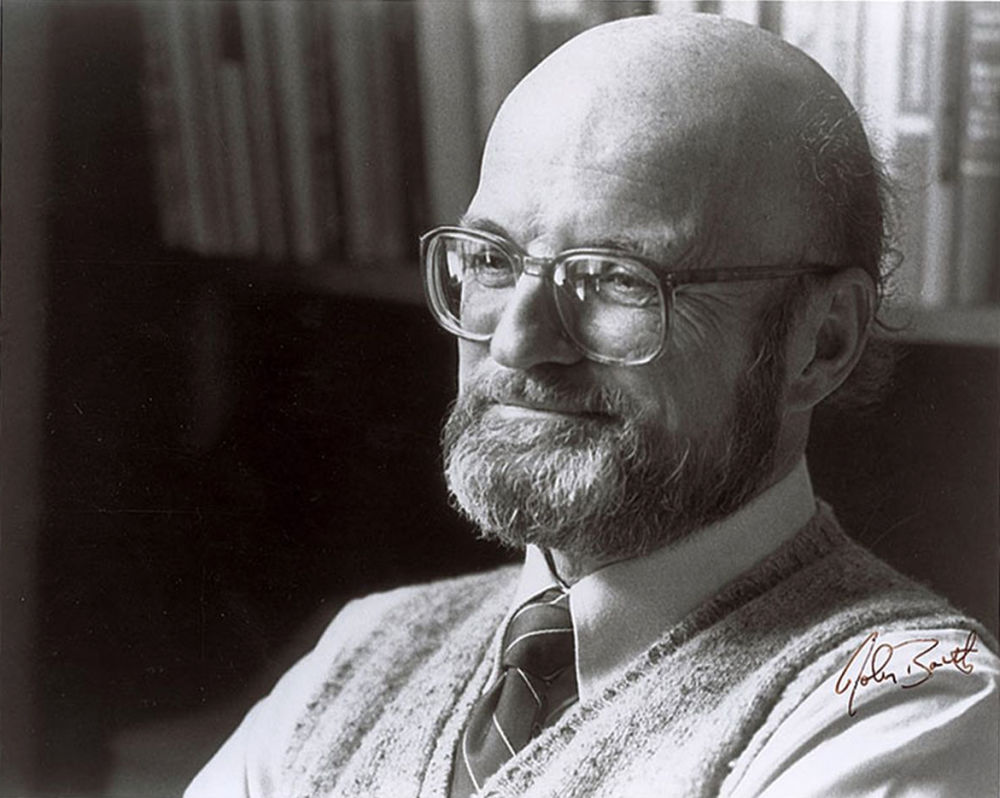

We were flying along the top of it in a white truck. The archaeologist Jan Simek, whom I’d just met in a parking lot, was driving (Jan as in Jan van Eyck, not Jan as in Brady). He’s a professor at the University of Tennessee who, for the past fifteen years, has led the work on the Unnamed Caves, as they’re called to protect their locations. We were headed to Eleventh Unnamed. It was a clear day in late winter, so late it had started to look and feel like earliest spring.

Simek (pronounced SHIM-ick) is a thick-chested guy in his fifties—bushy dark hair mixed with iron gray, sportsman’s shades. I’d expected a European from the name, but he grew up in California. His Czech-born father was a Hollywood character actor, Vasek Simek: he played Soviet premiers, Russian chess players, ambiguously “foreign” scientists. Jan looks like him. His manner is one of friendly sarcasm. He makes fun of my sleek black notebook and offers to get me a waterproof one like his, the kind geologists use.

Simek was unaware of the caves when he came to UT in 1984. Only a few sites had been uncovered at the time. His best-known work, the research that built his career, was all in France—not in the celebrated art caves, but at Neanderthal habitation sites. Simek had spent close to a decade working at Grotte XVI, a Paleolithic site in the Dordogne—a wide-mouthed open cave that had accumulated tremendously deep cultural deposits, and where the stratigraphy was all twisted, owing to the complicated hydrologic history of the cave. You couldn’t dig it like a normal place. A twenty-thousand-year-old artifact could show up below one that was thirty thousand years old. And when you hit those very deep strata, they’re so compressed, so thin, you end up looking for smearings of dark soil: Neanderthal fire pits. “I really do soil chemistry,” Simek said. His work at Grotte XVI has played a major role in the movement, over the last decade, to rehabilitate the Neanderthal, showing that they were more like us than we’d suspected, smarter and socially more complex (indeed they are us: we know now from DNA research conducted in Germany that most of us have Neanderthals in our family trees).

Simek had heard talk of Mud Glyph, however—the book on the cave, edited by his colleague Charles Faulkner, was coming out just as he arrived. When the task fell to him, as a new hire, of recruiting grad students for the TVA to use in its natural-resource surveys, he made a point of reminding them, before they went out, to check the walls of any caves they found. After years of doing this to no effect, some students burst into his office one evening, talking excitedly about a cave they’d seen, overlooking the Tennessee River, with a spider drawn on one of the walls inside. They competed to sketch it for him, how its body had hung upside down, with the eyes in front. Simek went to the shelf and pulled down a book. He spread it open to a picture of a Mississippian shell gorget with an all but identical spider in the center. “Did it look like this?” he asked.

That was First Unnamed Cave, “still my heart cave,” Simek says. When I visited it with him he showed me the spider. Also a strange, humanish figure, with its arms thrown back above its head and long flowing hair. First Unnamed happens to be the youngest of the Unnamed Caves. Its images date from around 1540. The Spanish had been in Florida for a few decades already, slaving. Epidemics were moving across the Southeast in great shattering waves. De Soto and his men came very near that cave in their travels, just at that time. The world of the people who made those glyphs, the Late Mississippian, was already coming apart.

We turned onto a side road, then onto another, more overgrown one, then started hair-pinning down into a valley. Only at the bottom, climbing out and gazing around, did I get a sense of what we’d descended into—it looked as if a giant had taken an ax and planted the blade a mile deep in the ground, then ripped it away. The forested walls went up, up, up on all sides. We started walking across the little narrow patchwork fields, the farm of the people who owned and protected this place. Jan had called them to say we were coming. Overhead was a wedge of blue sky, with storm clouds starting to mass at one end. Thunder filled the coves.

We approached a grotto. A curving, amphitheater-like hillside went down to a basin. It was Edenic. “No diver has ever been able to get to the bottom of that thing,” Jan said, indicating the blue-black pool of water. Frogs plashed into it at the sound or sight of us. We stepped sideways, following a half-foot-wide path through ferns and violet flocks, little white tube-shaped flowers whose name I didn’t know. Following a ledge around the pool, we reached the entrance.

Jan struggled with the lock on the gate. It looked like a mean piece of metal. I wondered if they weren’t overdoing it—that was before I’d heard all the stories of what some Tennesseans will do to get into caves they’ve been told not to enter, using dynamite, blowtorches, hitching their trucks to cave gates and attempting to pull them out of hillsides whole. Jan sent me back to the truck for motor oil, to lubricate the lock. I went gladly, jogging no faster than I had to back through that sanctuary, my pristine white caving helmet bouncing on my hip.

There survives a record of the first whites ever to see this place. In 1905 a local inhabitant came upon the journal of his great-grandfather, one of the original party who’d settled the valley in the 1790s, and he wrote it up for the paper. They’d journeyed from Maryland, men and women and children, with hopes of forming a tiny Utopia here, a community that would have its own laws. Their leader was a man named Greenberry—Greenberry Wilson. They brought a handful of slaves, who had musical instruments, and every now and then, supposedly, Greenberry would call a tune. “Old Cato gives the wink and the melody of old Zip Coon swells up on the forest air. The wild beasts listen at a distance, the dusky Indian maid approaches and look upon her white sisters’ enjoyment with envious eyes.” The descriptions are fanciful like that. It’s not clear to what extent you can trust them as transcriptions. The great-grandson seems to have been a drinker. He tells the same stories in wildly different ways, in the same newspaper, weeks apart. He’s clearly mixing details from the old journal with his own dreamings. I think at one point he admits he’s doing that, then at another tries to conceal it. The reason we know there was an eighteenth-century journal at all, that this descendant didn’t invent the whole thing, is that he has the settlers say the cave was full of mummies. There’s no other way he could have known that in 1905.

We prepare a good torch light and pass around to the right of the pond of water on a ledge or table of rock, there we enter a hall way ten or twelve feet wide, we travel this for fifty or sixty feet, and the hall begins to expand . . . Here jutting from the walls are tables or shelves covered with skeletons of vast proportions belonging to some passed age of the world.

The burials are still in there, covered with sediment that got washed through the karst when farmers started clearing the uplands around 1800. UT excavators found them out on the ledges, right where the journals said, silted over. The archaeologists left them alone, once they saw the bones peeking through the mud. All of their jewelry and other items for the afterworld had been stolen, probably—the little band of settlers had included a few eager looters. When they got done seeing the cave that day, they tore open the Indian mound two miles farther down the valley. The “party began in the center of the mound” and “secured many relics.”

Tearing open mounds is just what people did in America for the first few hundred years of white occupation. This makes it hard for us to imagine a landscape full of them. But the Native American societies of the East had been building them for five millennia, beginning with the Poverty Point culture in Louisiana, which predates even the monumental architecture of South America. Then you had the Adena, the Woodland, and the Mississippian, all mound-building cultures. Some were straight burial mounds, dirt heaped over the corpse of someone important or just beloved, others were symbolic, shaped like animals, such as the lovely and strikingly large bird- and snake-shaped mounds in Ohio and Kentucky. Finally, there were the giant flat-topped temple mounds, made by the Mississippian people, the purpose of which remains unclear. A mere fraction of these escaped the depredations of white looters. The first thing the Pilgrims did was loot a mound. It was literally the first thing they did. Myles Standish led a little group of them ashore. They followed a sand path. They saw a grave mound. It had a pot buried at one end and an object like “a mortar whelmed” (that is, upside down) on top. They discussed and decided to dig it. They pulled out a bow and some rotted arrows. Then they covered it up and moved on, “because we thought it would be odious unto them to ransack their sepulchers.”

Precious few of their descendants bothered with those scruples. On top of old-fashioned pioneer looting, such as the incident recounted in the journal, you had commercial mound-diggers in the nineteenth century (traveling on houseboats through the South, shoveling out pots and selling them in classified ads), followed by the pre-professional antiquarians who tore open untold mounds in the Midwest, leading to the Great Pyramid–level digs carried on under New Deal auspices in the thirties and forties. The sheer mass of material unearthed by those last excavations led to the first serious codification of Mississippian art and the birth of the Southern Cult as an idea. Two scholars, Antonio Waring and Preston Holder, noticed the profusion of certain images all over the South, and argued that these represented an evangelical movement, built on the worship of unknown gods.

The gate open, we switched on our head lamps. The same silty runoff made it harder now to get into the cave. We couldn’t simply “enter a hall way” like they did in the 1790s. Instead we squeezed through on our bellies. The mud had a melted Hershey’s quality. It oozed through the zipper in my dollar-store coveralls. The squeeze got tight enough that, as I wriggled on my stomach, the ceiling was scraping my back. Jan said they’d been forced to dig a couple of people out.

At last we came through and could stand, or stoop. I turned my head to move the beam up and down the wall: a light-brown cave. Jan had a bigger, more powerful, battery-powered light. He flashed it around.

“Stoke marks,” he said, nodding at a spot on the wall. His line of sight led to a cluster of black dots, like a swarm of black flies that had been smashed all at once into the stone. You could find them throughout the cave. They marked places, Simek said, where the ancient cavers had “ashed” their river-cane torches. The longer you went without doing that, the smokier it got.

He stopped and waited for me to catch up. He was facing the wall.

“First image,” he said, tightening his beam. “Double woodpeckers.” Faint white lines etched into the limestone. The birds were instantly recognizable. One on top of the other.

A conspicuous percentage of the caves, Simek said, had birds for their opening images.

“What does it mean?” I asked.

“We don’t know,” he said. I learned that this was his default answer to the question, What does it mean? He might then go on to give you a plausible and interesting theory, but only after saying, “We don’t know.” It wasn’t grumpiness—it was a theoretical stance.

Woodpeckers could be related to war, he said. In other Native American myths they carry the souls of the dead to the afterworld.

We advanced. There were pips—a small brown kind of bat—hanging on the wall, wrapped in themselves. Condensation droplets on their wings shone in our lights and made the little creatures look jewel encrusted. Jan, kneeling down to peer at something lower on the wall, got one on his back. He asked me to brush it off. I took my helmet and tried to suggest it away—the bat detached and flew into the darkness.

Jan went a few yards and then lay down on his back on a sort of embankment in the cave. I did likewise. We were both looking up. He scanned his light along a series of pictures. It felt instinctively correct to call it a panel—it had sequence, it was telling some kind of story. There was an ax or a tomahawk with a human face and a crested topknot, like a mohawk (the same topknot we’d just seen on the woodpeckers). Next to the ax perched a warrior eagle, with its wings spread, brandishing swords. And last a picture of a crown mace, a thing shaped like an elongated bishop in chess, meant to represent a symbolic weapon, possibly held by the chiefly elite during public rituals. It’s a “type artifact” of the Mississippian sphere, meaning that, wherever you find it, you have the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, or, as it used to be called (and still is by archaeologists when they think no one’s listening), the Southern Death Cult. In this case the object appeared to be morphing into a bird of prey.

What did it mean?

“We don’t know,” Simek said. “What it is clearly about is transformation.”

Everything in it was turning into everything else.