A few years ago, during a visit to Colombia, I wanted to photograph a prison, and I wound up at Valledupar, a state-of-the-art facility, designed and paid for by the United States. During my visit I met the prison’s most notorious inmate, a man known by the alias Popeye, who had spent much of his working life as the “head of security” for Pablo Escobar, the godfather of the Medellín cocaine smuggling cartel. Popeye was held responsible for at least a hundred and fifty murders. I found him reading Homer’s Iliadin the prison’s high-security wing. Popeye was a personable hit man and he told vivid stories of his years in the employ of Escobar, who had killed half of the country’s top judges, stormed the Supreme Court to destroy evidence, bombed the national intelligence headquarters and one of the leading newspapers, and blown a commercial airliner out of the sky. In 1989, when Escobar said, “Death to the police in the city,” Popeye enlisted subcontractors for a volume of assassinations that he could not personally handle: “It was one million pesos for a dead policeman, two million for a dead corporal, three million for a sergeant, four million for a lieutenant, five million for a captain, ten million for a major, fifty million for a colonel, and one hundred million for a general,” he said, and added, “Pablo Escobar always thought big.”

At the height of his war with the state, Escobar’s cause was not drugs so much as drug policy, and specifically Colombia’s extradition treaty with the United States. It enraged Escobar that he could be taken from his home to face prosecution in a foreign country. “We prefer a tomb in Colombia to a prison cell in the United States,” he declared, and he swore that the day that Colombia repudiated extradition he would surrender. Sure enough, Colombia changed its policy, and Escobar agreed to go to jail with a number of his closest henchmen—albeit in a private prison that he built himself in Medellín, a prison where he could throw parties and conduct business and from which he ultimately escaped. The final two years of his life were spent as the target of a relentless manhunt. He evaded thousands of raids, sometimes by hiding, brazenly, in plain sight—strolling with Popeye through the streets of Medellín as if they were not two of the world’s most-wanted men. “The man was totally cold,” Popeye said. “He was supernatural.”

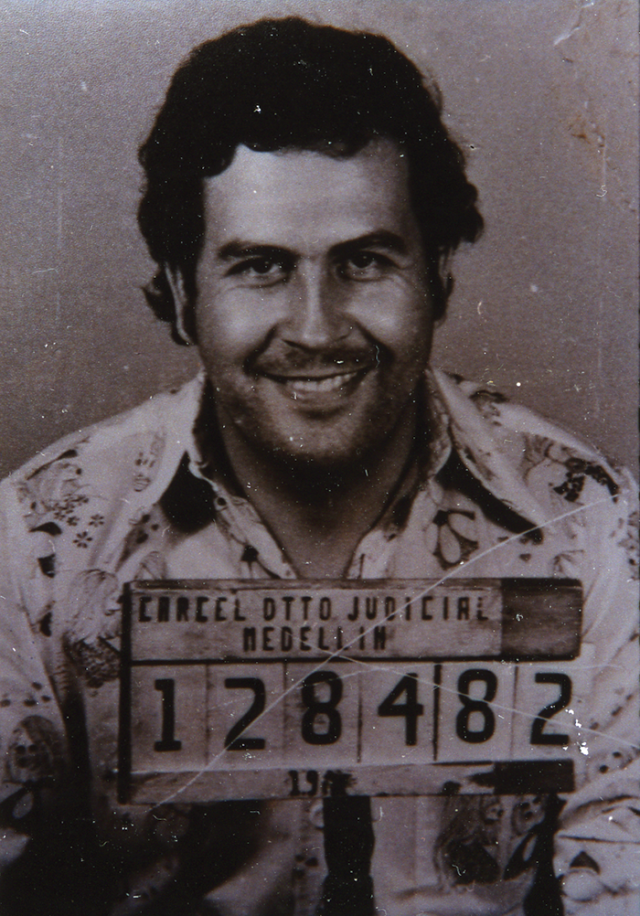

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria’s mug shot following his arrest, in 1976, for attempting to ship eighteen kilos of coca paste into Colombia from Peru. Escobar avoided prosecution by murdering the two agents who arrested him.

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria’s mug shot following his arrest, in 1976, for attempting to ship eighteen kilos of coca paste into Colombia from Peru. Escobar avoided prosecution by murdering the two agents who arrested him.

I wanted to know more. My next project in Colombia was to photograph narcotecture—the influence of drug money on the country’s architecture. I made a tour of properties reportedly built by drug smugglers in Medellín—lavish fincas, extravagant nightclubs, blocks of flats with swimming pools on their terraces. By comparison to their legend, these buildings were invariably dull, even shabby, and none more so than the last on my list, Edificio Monaco, which had been Escobar’s residence until his Cali cartel enemies bombed it. The place looked more like a concrete office block or a six-story bunker than a home—ugly and characterless. I set up my tripod in the street outside, but I was soon apprehended by security officers who confiscated my camera and escorted me off to see “the boss.”

It turned out that the building was now the local headquarters of the Fiscalía, Colombia’s public prosecution service, and I was in breach of security rules. When I told the boss, Manuel Darío Aristizábal, that I was taking pictures because this was once Pablo Escobar’s house, he proudly informed me that his office used to be Escobar’s bedroom and that the beat-up leather sofa I was sitting on was originally Escobar’s sofa. Then he said, “I have a bag of Pablo Escobar photographs—would you like to see them?”

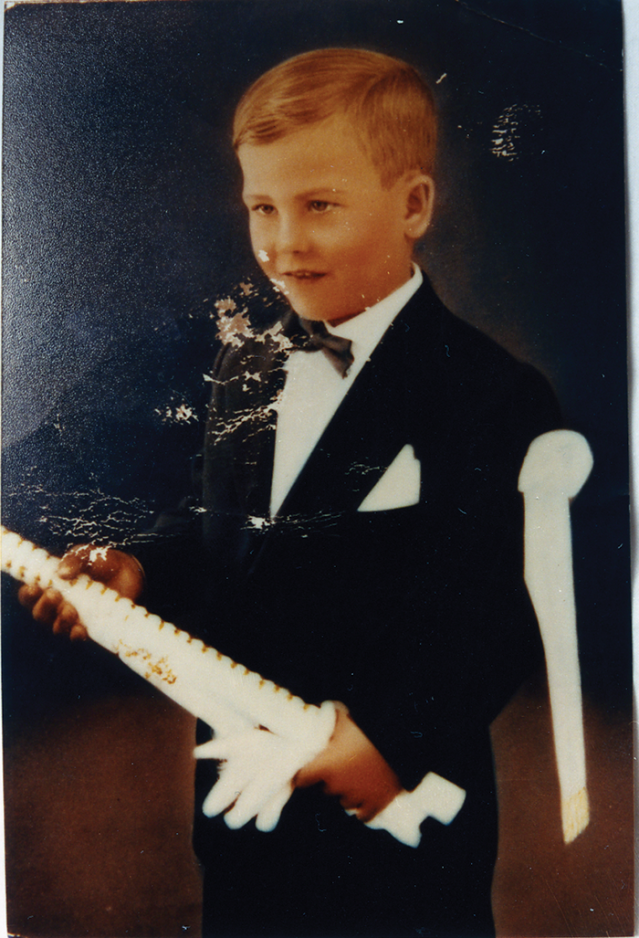

Escobar’s first communion, age six, 1956.

Escobar’s first communion, age six, 1956.

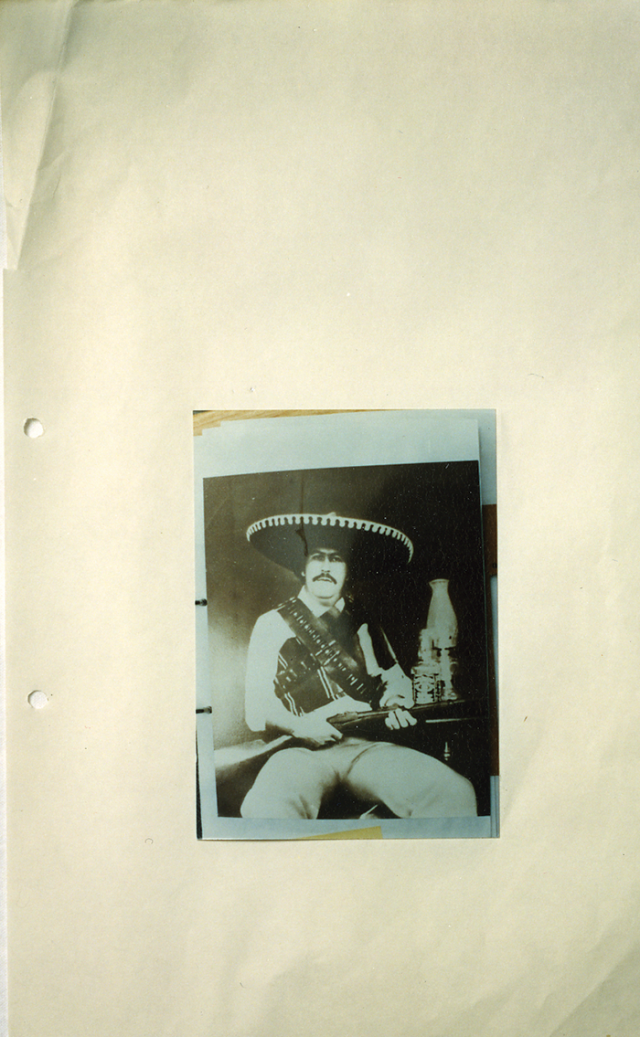

Escobar dressed as Pancho Villa, circa 1981. Pablo had the picture framed and hung in his prison cell.

Escobar dressed as Pancho Villa, circa 1981. Pablo had the picture framed and hung in his prison cell.

The photographs were from Escobar’s police files, images recording the scene at his private prison in Medellín after his escape. Like the room in which I was sitting with Aristizábal, the pictures didn’t fit the image of underworld opulence I’d heard and read about. There were photographs of guns and sex toys in his hideaways, but other images of Escobar playing with his family, of his gang playing soccer or drinking in the prison “disco,” and of his Mickey Mouse slippers suggested a more ordinary man, at once more complex and less glamorously evil than I’d imagined him. Sitting in Escobar’s former bedroom, somewhere between his myth and his reality, it occurred to me to explore his legacy by reconstructing Pablo Escobar’s story in photographs.