Pink Whale, 2017, colored print on paper, 19" x 15 2/5 ".

Pink Whale, 2017, colored print on paper, 19" x 15 2/5 ".

“Once things leave my files,” Etel Adnan wrote to me, “I never know where they are, and don’t think about them anymore, otherwise you lose your mind.” Her method is sound: now ninety-three, she has made hundreds of works over seven decades and shows no signs of slowing. She made the painting on the cover of this issue in January, especially for The Paris Review (the pencil marks are hers, too). So numerous are her paintings, drawings, films, tapestries, ceramics, and murals that I imagine it must be impossible to see them all; so brisk and vital are they that I am always eager for more—and amazed by the beauty she discovers each time.

Adnan was born in Beirut in 1925. Her mother was from Smyrna, her father an Ottoman officer from Damascus; at home, they spoke Turkish and Greek, and she was educated in French. She studied philosophy at the Sorbonne and traveled from there to Berkeley and Harvard. It was the United States—California specifically—that made Adnan a painter. She took her first art class at Dominican College, north of San Francisco, where she was teaching the philosophy of art. When the war for Algerian independence began in 1954, she became hardened against the French language, in which she had been writing poetry. “Painting,” she says, “opened to me a different way of expression. And as my Arabic was poor, in some moment, as a defiance, I happened to say, I will paint in Arabic!” The California landscape awakened her spiritual instincts and focused her gaze. While living near Mill Valley, she had daily views of Mount Tamalpais. “To observe its constant changes became my major preoccupation,” she has written. “I even wrote a book in order to come to terms with it—but the experience overflowed my writing. I was addicted.”

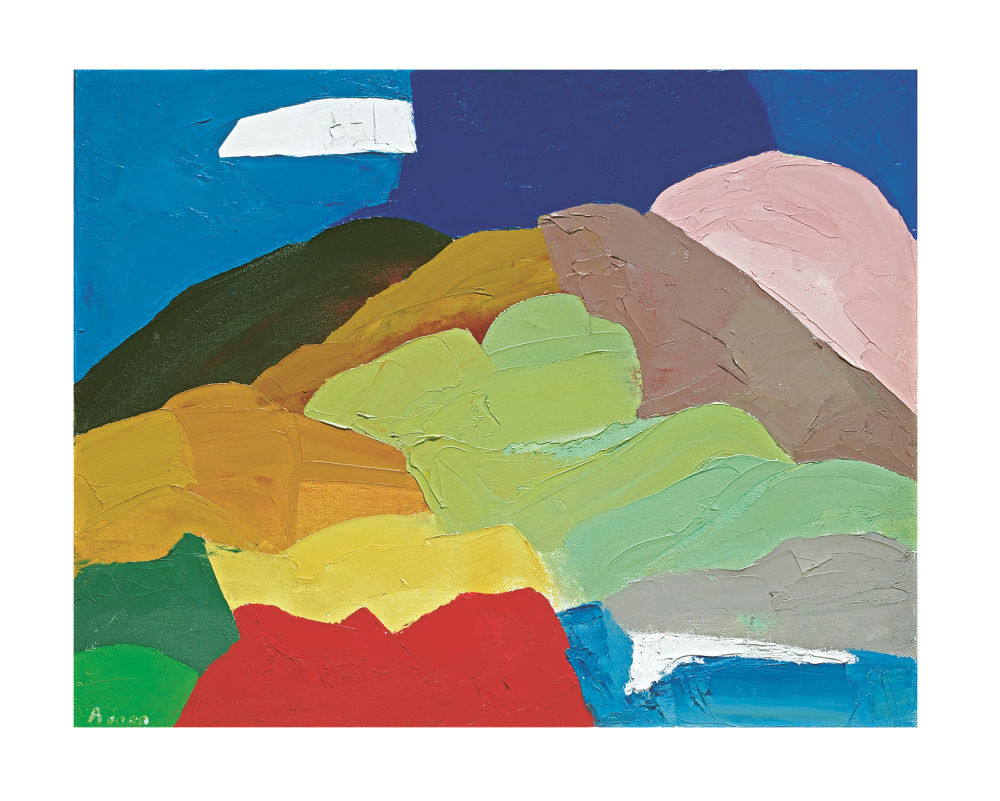

Adnan never left the mountain behind. It appears decade after decade in various guises: as monochromatic mounds, thin washes of color, accumulations of brushy strokes. Her landscapes, too, are variations on a theme—minimal fields of color describing anonymous grassy hills, alluvial plains, quiet oceans—but each color combination, each arrangement of forms evokes a new mood. In Journey to Mount Tamalpais, published in 1986, Adnan writes that the “pyramidal shape of the mountain reveals a perfect Intelligence within the universe. Sometimes its power to melt in mist reveals the infinite possibilities for matter to change its appearance.” That mystical geometry extends to the cosmos, the busy orbiting of swift planets and the pendulous drift of the sun and moon—celestial bodies that both possess a physical reality and act as gateways to another place or dimension. “Voyager 2 has already travelled 2 billion miles,” she writes in Journey. “We are well engaged into the outer frontiers. And further on, when we will go beyond the reaches of Space and Time, something else will open up, we will know what it means for the human species to become an Angel.”

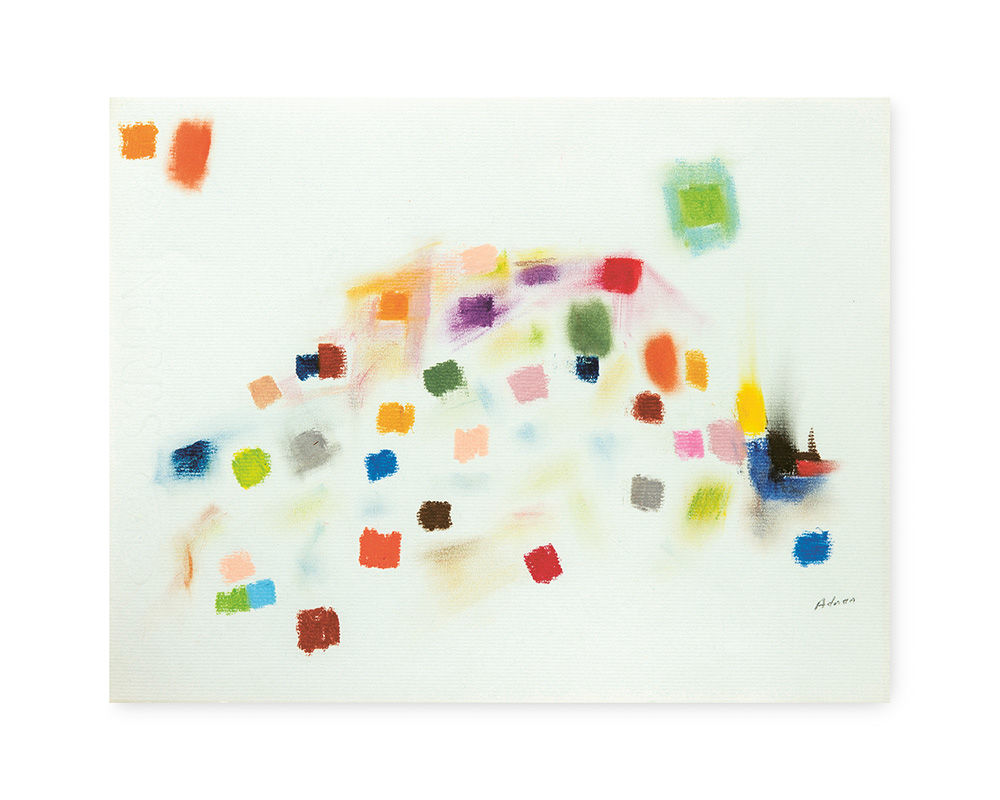

Color is essential to these transfigurations. When Adnan sees Tamalpais topped with snow, she muses that “white is the color of terror in this century: the great white mushroom, the white and radiating clouds, the White on White painting by Malevich, and that whiteness, most fearful, in the eyes of men.” Color is energy, a visionary pathway linking the earth and the universe. In that space, she gathers prophesy and myth, Arab mystics and Soviet cosmonauts, Friedrich Nietzsche and Eleni Sikélianòs. In a gouache and ink painting made in the eighties, she encircles the names of writers and artists she admires in bubbles rising against a loose grid of color, like a cultural solar system.

(Mt. Tamalpais 1), ca. 1995–2000, oil on canvas, 14" x 18".

(Mt. Tamalpais 1), ca. 1995–2000, oil on canvas, 14" x 18".

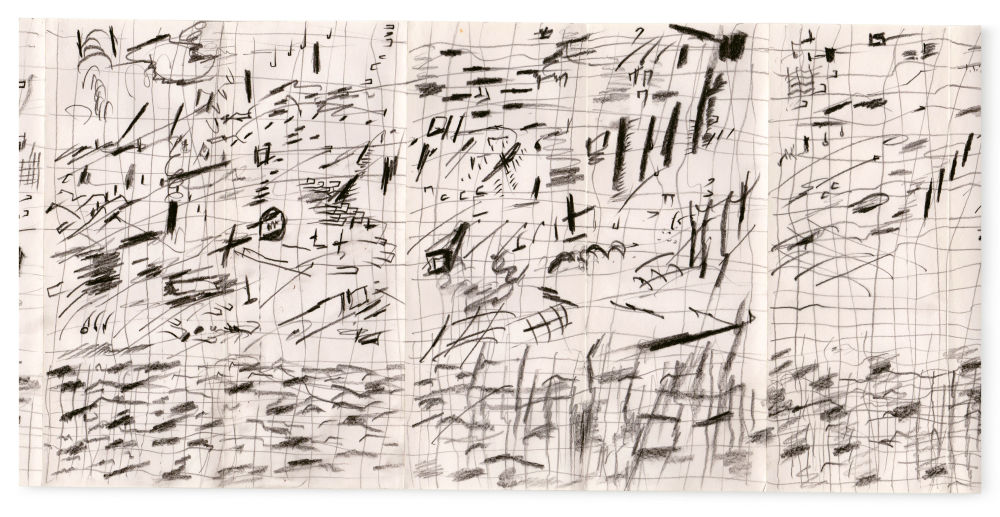

In 1965, Adnan wrote what she has called her first American poem, in response to the escalation of the Vietnam War. Composing in English was “an adventure . . . a sport,” she has said. “Sentences were like horses, opening space in front of them with their energies, and beautiful to ride.” Three years later, she produced her first leporello, an accordion-fold book that extends several feet in length; her longest is more than seventeen feet. On some of these, she copied Arabic poetry calligraphically, using ink and watercolor, rendering the poems visually, as landscapes of verse. In others, drawings gallop from page to page, unfurling, literally, across time.

East River Pollution, “From Laura’s window,” New York, April 79, 1979, crayon and pencil on paper, thirty pages, each 8" x 3 1/5 ", max. extension 7 ' 4/5 ".

East River Pollution, “From Laura’s window,” New York, April 79, 1979, crayon and pencil on paper, thirty pages, each 8" x 3 1/5 ", max. extension 7 ' 4/5 ".

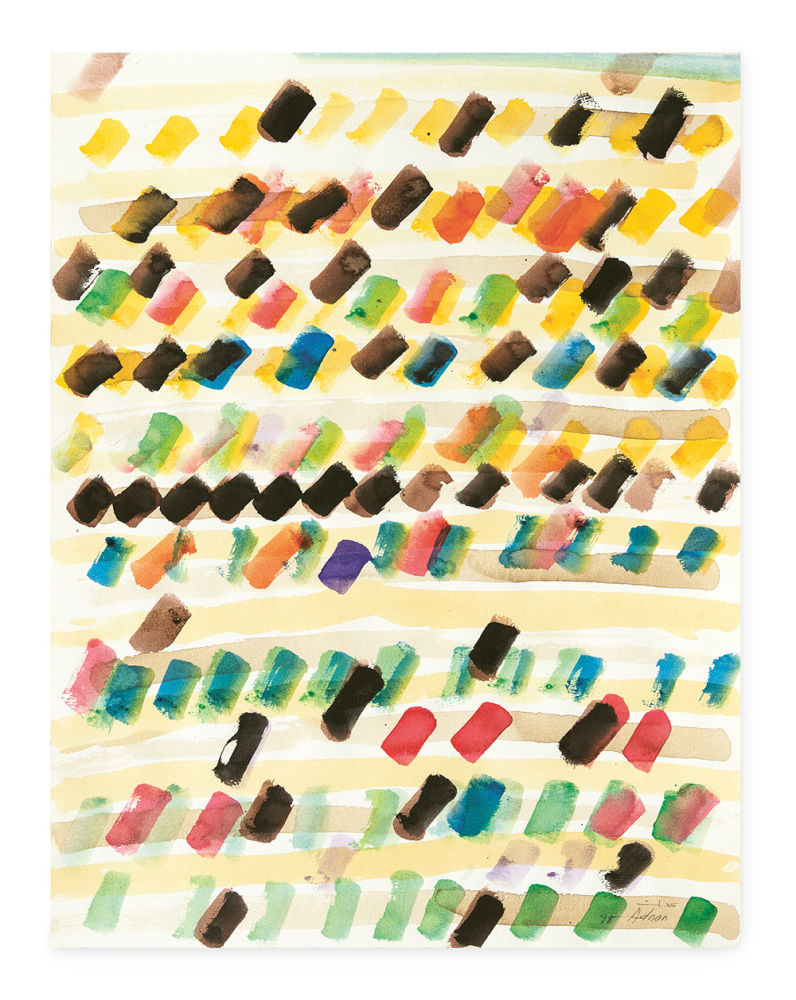

Untitled, 1998, watercolor on paper, 25 3/5 " x 19 ¾ ".

Untitled, 1998, watercolor on paper, 25 3/5 " x 19 ¾ ".

Untitled, ca. 1970, pastel on paper, 9 ½ " x 11 4/5 ".

Untitled, ca. 1970, pastel on paper, 9 ½ " x 11 4/5 ".