William Styron Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University, and is (c) The Estate of William Styron.

In the fall of 1985, the writer William Styron fell into a deep depression. The author of celebrated novels such as The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967) and Sophie’s Choice (1979), he ceased writing that autumn and entered a period of intense brooding and near-suicidal despair. He was admitted to the neurological unit of Yale–New Haven Hospital on December 14 and stayed there for almost seven weeks. Rest and treatment allowed him to regain his equilibrium; he returned to his home in Roxbury, Connecticut, in early February, and by that summer was writing again.

The untitled novel from which “Spiral” is taken was begun in spring 1988 and represents Styron’s first attempt to address the subject of depression. The narrator of this novel, Paul Whitehurst, is a successful playwright, famous for his early work and a celebrity in the theater world. Despite his creative success, when the story opens he is plagued by an unshakable malaise. Paul’s narrative is based closely on Styron’s recollections of his own breakdown and hospitalization. The novel begins strongly, but after the opening sequence of Paul’s first day at the hospital, recounted in all its disorienting detail, the prose veers from fiction toward exposition. Styron had read widely in the literature of clinical depression and had learned a great deal about its history, its etiology, and its smothering effect on the human mind. In the later parts of the manuscript he seems determined to tell all he knows, but he cannot find a way to do so within a fictional framework. The plotline becomes unclear and the characters undistinguished (with the exception of Francesca, Paul’s wife, who is modeled on Rose Styron, the author’s wife). Styron, a rigorous self-critic, recognized these shortcomings and set the novel aside in fall 1988.

The following summer, he decided to tell the story of his depression in a first-person memoir. The result was an essay that first appeared in Vanity Fair and was subsequently expanded into a short book, Darkness Visible (1990). In Darkness Visible the author spoke with clarity, candor, and insight on behalf of those who had suffered from depression, framing the narrative around that 1985 depressive episode, which occurred on what should have been a celebratory trip to Paris.

While Darkness Visible has become Styron’s iconic contribution to the literature of psychology, “Spiral” is the author’s initial attempt to set down the story of his depression, to document the complexity of the disease and its malefic effect on personality and behavior. The text is taken from the surviving manuscript, a handwritten draft preserved among Styron’s papers at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University, published here with the permission of InkWell Management on behalf of the Estate of William Styron.

Spiral

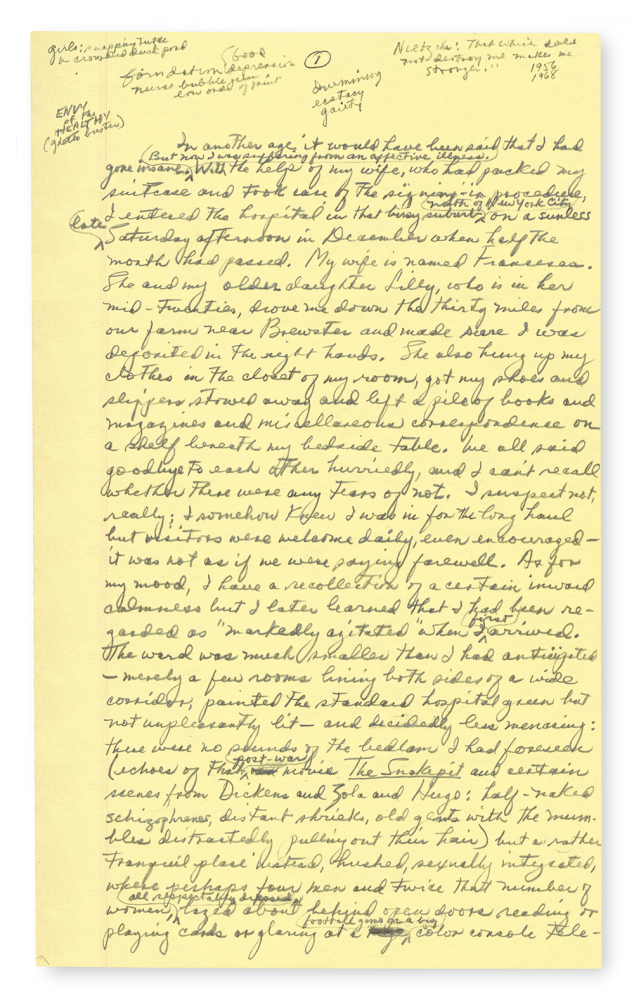

In another age it would have been said that I had gone insane. But now I was suffering from an affective illness. With the help of my wife, who had packed my suitcase and taken care of the signing-in procedure, I entered the hospital in that busy suburb north of New York City on a sunless Saturday afternoon in December.

My wife is named Francesca. She and my older daughter, Lilly, who is in her midtwenties, drove me the thirty miles from our farm near Brewster and made sure I was deposited into the right hands. Francesca also hung up my clothes in the closet, got my shoes and slippers stowed away, and left several stacks of books and magazines and miscellaneous correspondence along the wall. We all said goodbye to each other hurriedly. I can’t recall whether there were tears or not. I suspect not, really. I somehow knew I was in for the long haul, but visitors were welcomed daily, encouraged even. It was not as if we were saying farewell.

As for my mood, I have recollection of a certain inward calmness, but I later learned that I had been regarded as “markedly agitated” when I arrived. The ward was much smaller than I had anticipated—merely a few rooms lining both sides of a wide corridor, painted the standard hospital green but not unpleasantly lit—and decidedly less menacing. There were no sounds of the bedlam I had foreseen (echoes of that postwar movie The Snake Pit and certain scenes from Dickens and Zola and Hugo: half-naked schizophrenes, distant shrieks, old gents with the mumbles distractedly pulling out their hair). This was a rather tranquil place—hushed, sexually integrated, where perhaps four men and twice that number of women, all respectably dressed, lazed about behind open doors, reading or playing cards or glaring at a football game on a big color console television set.