Issue 129, Winter 1993

The intimacy of William Stafford’s poetry would seem to belie the enormous popularity the poet’s work has enjoyed, but in fact it is a product of Stafford’s keen ability to discern poetic language in everyday speech and appropriate it for his own work. Stafford, whose first volume of poetry was not published until 1960 when he was forty-six, was born in the small town of Hutchinson, Kansas on January 17, 1914 and died in Portland, Oregon on August 28, 1993 at the age of seventy-nine.

After taking his bachelor’s degree at the University of Kansas in 1937, he spent most of World War II in government internment camps for conscientious objectors. He worked as a laborer in sugar-beet fields, at an oil refinery, and for the United States Forest Service. His novel Down in My Heart (1947) is a fictionalized account of his experiences as a wartime firefighter, construction worker, and finally, as a staffer at the Church of the Brethren in Illinois. In 1955 Stafford completed a Ph.D. in literature and creative writing at the University of Iowa. His first volume of poetry was West of Your City. Traveling through the Dark, his third collection (a facsimile manuscript page of the title poem appears with this interview), won the 1962 National Book Award.

Stafford wrote over fifteen books in his thirty-three-year publishing career, making him one of the country’s most prolific poets. His books include the poetry collections Stories That Could Be True: New and Collected Poems (1977), An Oregon Message (1987), and Passwords (1991), and two widely read books on the writer’s vocation, Writing the Australian Crawl (1978) and You Must Revise Your Life (1986). He served as Poetry Consultant to the Library of Congress in 1970 and 1971, and has received many literary prizes and honors, including the Shelley Memorial Award, the Award in Literature of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

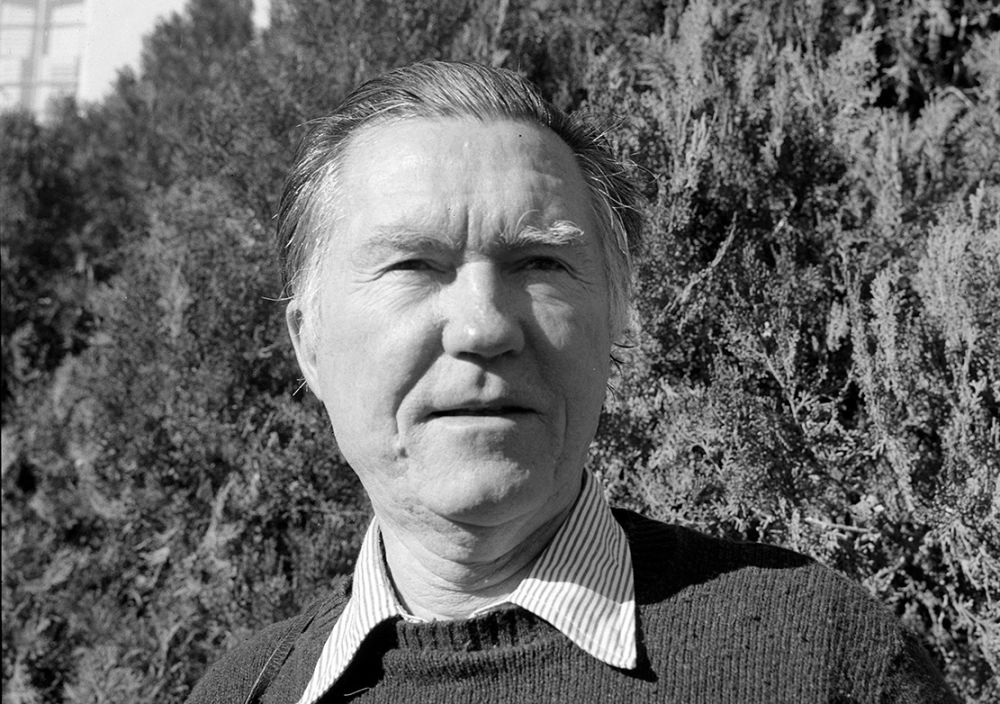

Stafford taught at Lewis and Clark College in Portland from 1960 to 1978, and until his death, made his home in nearby Lake Oswego. This interview was conducted over two days in an elementary-school classroom in Cannon Beach, Oregon, where the 1989 Haystack Writer’s Workshop was taking place. Stafford and his son, the writer Kim Stafford, were there jointly conducting a workshop on writing poetry and lyrical prose. During the conference, Stafford carried a camera around with him, frequently stopping to take pictures. For the interview, we sat in school desks across from each other. Stafford wore a plain white cotton shirt, open at the collar and loose, unpressed cotton pants. He had a broad, somewhat owlish face, his self-effacing manner and appearance in sharp contrast with his fiercely independent nature.

INTERVIEWER

In his essay on James Wright, Richard Hugo wrote, “The luckiest thing that ever happened to me was the obscurity I wrote in for many years.” Do you feel similarly about your own late-blooming career as a poet?

WILLIAM STAFFORD

I think I understand what Hugo was getting at: that you are ambitious when you start and if you have a whiff of success you try to rush things; for publication’s sake you try to rush it all the more; then the ordinary slumps in popularity and intervals when you’re not publishing become overwhelming simply because you haven’t gotten used to doing what you have to do as a writer—write day in and day out no matter what happens.

INTERVIEWER

In your poem “A Living,” you write there is “a way to act human in these years the stars / look past.” What kept you from responding in more extreme ways, more “human” ways . . . did you feel like the stars were looking past you during certain years?

STAFFORD

In that poem, at least, I was thinking about the feelings many people have of tension, of questioning about survival, of the hovering of the atom bomb, all kinds of disquiets that people have in our times. I think I was referring to that more than to my personal experience. In fact, I had early and sustained publication, every bit that I deserved. I never did feel left out for any reason. I felt pretty lucky.

INTERVIEWER

In another essay, Hugo places you among writers he labels Snopeses, a reference to the Yoknapatawpha County family from Faulkner. These writers, he speculates, are basically outsiders and thus are afraid success will cause them to lose touch with other outsiders.

STAFFORD

I understand Hugo’s impulse to stay in touch with outsiders. He was a natural outsider. But on the other hand he couldn’t be an outsider; he was taken in by everybody; they loved him. He was addicted to sociability, helplessly social. And he was addicted to, or available to, the heartiness of interchange among writers. He enjoyed company and sympathy and liked to extend sympathy. He especially valued that feeling of kinship with people who were failures or outsiders. My own feeling is that I’m not sure what being an outsider amounts to. Maybe some of us should be outsiders. I’m not sure by any means that I deserve to be an insider, whatever that would be. Maybe one feels neglected only if one has an opinion of one’s rightful place, and I don’t have that opinion. That’s up to the world.

INTERVIEWER

Have many of your friends been writers?

STAFFORD

Not very many. Because of living so long and traveling around, I’ve met many writers, and I enjoy meeting them. Hugo is an example. He used to come and stay at our house. We were always delighted to have him. But in my daily life I don’t live in proximity with, or in daily, person-to-person communication with writers at all. When I write, writers don’t see what I write, only editors. My family doesn’t see it either.

INTERVIEWER

So you don’t exchange poems with writers?

STAFFORD

No. Well, it’s possible. Hugo has actually written me, in the breezy way he had of ending a letter: What does the earth say, oh sage? I would always write something back to him. In one particular poem, “The Earth Says This,” I took up the challenge. But that was very rare.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a sense of being at home in the world in your poems. And you’ve said as much explicitly. The insecurities many writers seem to feel, especially in the twentieth century, seem somewhat absent from your work?

STAFFORD

I do feel at home in the world. I have genuinely felt throughout my life a sense that any acceptance of what I write is a bonus, a gift from other people. It’s not something that’s due me. When any editor has a place for some of my work, that’s fine, but I always send that stamped return envelope. I’m genuinely ready for those rejections. I’ve always felt that an editor’s role is to get the best possible material for the readers of the publication, not to serve the writer, not at all. If they don’t want it, I don’t want them to have it. So I never have felt that I needed to push this stuff into the world. If it’s invited in, then it will come in. If it’s not invited in, fine, it will live at home.