Issue 126, Spring 1993

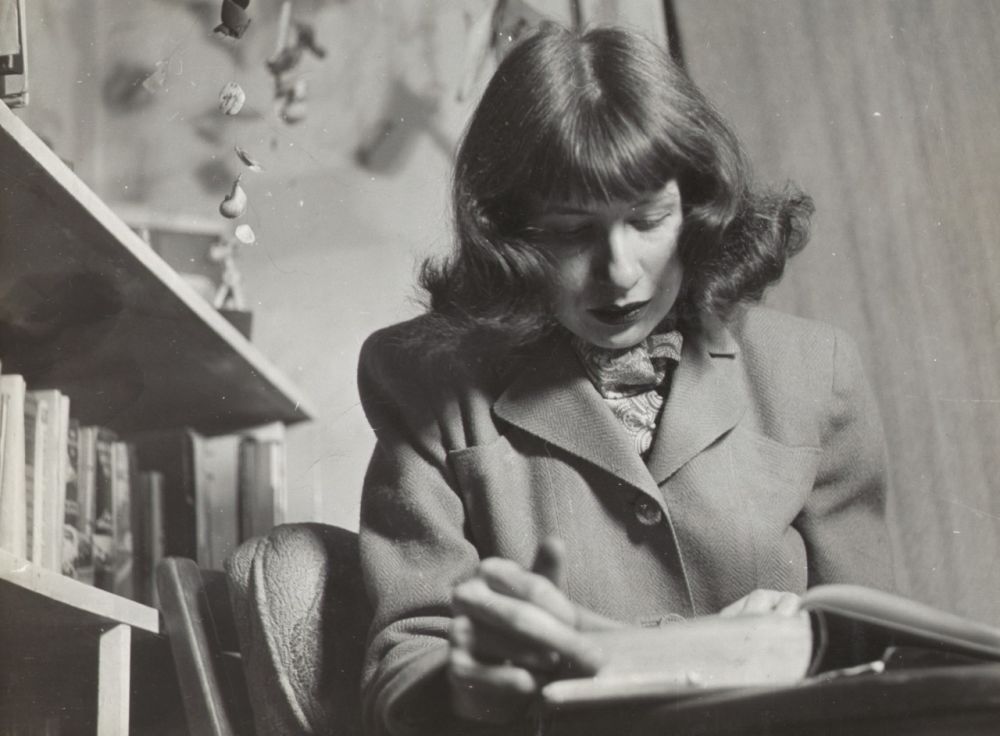

Courtesy of Berkshire Taconic Community Foundation

Courtesy of Berkshire Taconic Community Foundation

Amy Clampitt’s childhood was spent in the small farming village of her birth, New Providence, Iowa, where at the age of nine she began to write poetry. Taking a bachelor’s degree with honors in English at Grinnell College and a Phi Beta Kappa key as well, Clampitt began graduate study at Columbia University, but left to work for the Oxford University Press. In 1951 she spent five months in Europe, returning to work as a reference librarian for the National Audubon Society (1952–1959), freelance editor and researcher (1960–1977), and editor at E. P. Dutton (1977–1982). Since 1982 she has been a full-time poet, with occasional semesters as a college teacher.

Her first two books of poetry, Multitudes, Multitudes (1974) and The Isthmus (1981), both printed by small presses, attracted little attention. Though her first major book of poetry, The Kingfisher (1983), was published less than ten years ago, this poet from the American heartland has become a major voice in contemporary American poetry, respected not only here but in England, where Faber & Faber has followed Knopf in publishing each collection. With each of the books that followed (What the Light Was Like, 1985; Archaic Figure, 1987; Westward, 1990), she has fulfilled the promise Edmund White and others discerned in The Kingfisher. Critics laud her for “a brilliant aural imagination” (Joel Connaroe), for an erudition that is impressive, for a linguistic elegance that energizes her verse. Yet what may be most impressive is her passionate articulation of the pain experienced by those victimized and marginalized, whether the nineteenth-century American feminist Margaret Fuller, the Victorian novelist George Eliot, or an anonymous Greenwich Village neighbor.

Today she publishes regularly in the most respected journals and magazines. Few contemporary poets—male or female—occupy such a distinguished place in American letters. She was recently awarded a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Fellowship, the latest in a series of awards that have included a Lila Wallace Readers Digest Writer’s Award, a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, an American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters Award, and a Rockefeller Foundation Residency at the Villa Serbelloni in Bellagio.

Clampitt’s writing extends beyond her own poetry. She has translated cantos from Dante’s Inferno as one of a number of contemporary poets participating in a project designed by Daniel Halpern. She has published a number of essays and reviews, many of them gathered in Predecessors Et Cetera. She is presently at work revising a play on Dorothy Wordsworth and her circle, tentatively titled “A Guilty Thing Surprised.”

Clampitt has devoted considerable time to teaching in recent years. She has held appointments as writer in residence at the College of William and Mary and at Amherst College; in December 1991 she was Elizabeth Drew Distinguished Professor of English at Smith College where, during the spring term of 1993, she will be the first writer to serve as the Conkling Distinguished Writer-in-Residence. When not holding appointments elsewhere, Clampitt lives in New York City with annual summer holidays taken on the coast of Maine.

The series of conversations that comprise this interview took place in Boston during the November of 1991 when Clampitt participated in a reading at Boston University and during her appointment at Smith the following month.

INTERVIEWER

You are a product of a place very different from where you now spend most of your time, from where we are right now. You were born and brought up in Iowa, a child of the prairie. How do you see your early experiences in America’s heartland? Did you really mean it when you once spoke of yourself as “a misfit from the Midwest”?

AMY CLAMPITT

I was in the middle, and I didn’t want to be there. I was conscious of that from as early as I can remember. My own sense was that nothing authentic was there, that everything was derived from somewhere else, and I wanted to get near to where things were derived from. It has something to do with the geographical nature of the region, its being a hollow, a depression. It isn’t like Europe, with its mountain barriers and raised places where you can get up and look out, all those edges and coastlines. For some reason I thought it would be more interesting, and that one would be closer to real things, if one was at the edge.

INTERVIEWER

Your poem “Imago” gives us a glimpse of you as a child, “the shirker propped above her book in a farmhouse parlor . . . eyeing at a distance the lit pavilions that seduced her.” What was home like?

CLAMPITT

That image goes back to the first house I remember, a farmhouse parlor I can picture vividly; I used to lie on the rug, propped on my elbows, and read there. One of the books I read was an old copy of Hans Christian Andersen with strange, very nineteenth-century engravings. It was so old that the outer covers were gone. There was some kind of awful fascination about those stories; they’re not cheerful, they’re a glimpse into the adult world, and I think I was entranced by them for that reason. I think the happiest times in my childhood were spent in solitude—reading such stories. Socially, I was a misfit. I didn’t know the right things to say to anybody. I had no confidence that I could prevail in anybody’s mind as having anything to say.

What I most enjoyed was the order of the seasons and especially the arrival of spring, which, when you are small, comes from a great distance. In the late summer there would be the threshing season, which totally vanished once the combine came in. In those days the grain had to be cut and tied into bundles, and the bundles put into shocks to keep the rain off, and then the day came when the entire community would be involved in bringing in the grain and feeding it into the threshing machine and taking away the threshed grain and stacking the straw. This is something I’ve written about. The boys in the family would be out bringing water to the men in the fields, the girls involved in the kitchen, cooking a huge meal at noon for all the crew; and this was something you looked forward to. Then at the end of the season there would be what they called the “settling up,” when the balances were arrived at—so and so contributed so much labor and so on, and that would take place at somebody’s house, and there’d be ice cream for everyone, games of hide-and-seek in the shrubbery outside, that sort of thing. Those are the pleasantest memories. I have some winter memories, too, of riding in a sleigh, of an evening of bobsledding on a steep hill; the whole community turned out. There were a lot of relatives, a lot of cousins, and at Christmas there would usually be a huge family gathering—pleasant in a way, yet I remember being miserable. I couldn’t deal with all the people who sounded so sure of themselves when I didn’t feel sure of anything.

INTERVIEWER

What texts, other than Hans Christian Andersen, became important to you now that you think back?

CLAMPITT

Strange things. Oscar Wilde’s The Birthday of the Infanta. I read many books at my grandfather’s house. My grandfather was the great solace. He didn’t have a lot of formal education, but he had a feeling for words and a sense of the past, a sense of being involved in something larger than his own immediate concerns. He subscribed to the Book-of-the-Month Club, and so I remember for instance reading Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter and Willa Cather’s Shadows on the Rock, with the Knopf borzoi on the title page. I remember reading The Bonney Family by the Iowa novelist Ruth Suckow. The books I read were not all great classics. I did read the sonnets of Shakespeare quite early. I discovered Keats when his poetry was assigned to me by a teacher in high school. Swinburne and Edna St. Vincent Millay were my favorites before Keats was, actually. I can’t give you a list. I met somebody lately who kept a list of everything she read from the time she was twelve. Now that would be an interesting exercise.

INTERVIEWER

If I’m correct, your earliest ambition was to be not a writer, but a painter. Does that take us back to those illustrations in Andersen or to some other place?

CLAMPITT

I vaguely remember my mother subscribed to some art magazines. I have a clear picture of what I thought a painting was—it was of a Madonna and child. When I was eight or nine, I thought that’s what I wanted to do, paint old masters.

INTERVIEWER

What sorts of things did you write when you first started? Were they modeled upon what you read, or were they just sheer invention?

CLAMPITT

I remember writing a poem in which the word beautiful appeared. What it was about, I have no idea. I think I knew that I had misspelled beautiful. I don’t think it was modeled on anything particular. Later when I started writing poetry, mostly I wrote sonnets. They would have been modeled on Shakespeare, I suppose. I also tried to write stories. I had a notion even before I went to college that a career as a writer of fiction was possible. When I graduated from college in 1941, it was really ridiculous to admit to being a poet. Poets were looked upon as figures of fun . . . a kind of threat, really, to the way other people lived. Edna St. Vincent Millay, whom I admired, was a ridiculous figure in a way. So in those days I thought it would be all right to be a novelist, publish something, and make a little money. Being a poet was too much to take on.

INTERVIEWER

Philip Larkin comes to mind because he always maintained that he would much rather have been a novelist than a poet. He wrote two novels and had them published, but the third one never really got finished. You wrote a couple of novels, didn’t you?

CLAMPITT

I wrote three novels. I can hardly remember them. I don’t have any wish even to think about them now. I didn’t know how to write a novel. For quite a while, I was really so caught up in just living from day to day that all I wrote were fragments. They had to do with memories of my childhood.

INTERVIEWER

How valuable were your days at Grinnell?

CLAMPITT

In some ways those four years were a kind of wandering, lost and not knowing what to do with myself. I knew how to get good grades, I could write papers and all that, but I can’t say I really learned how to think. The greatest excitement came from a course I took my senior year in the history of art. That for some reason made history real to me in a way that nothing else did. I couldn’t envision large public events; I couldn’t think the way historians think about armies and troop movements, but to see the buildings that had been left behind was tremendously thrilling.