Issue 169, Spring 2004

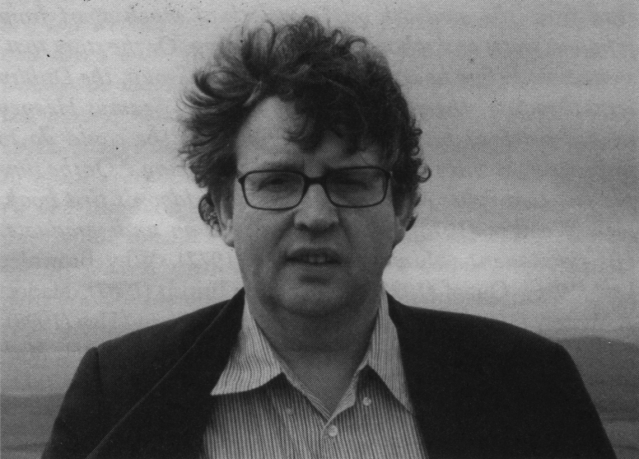

Paul Muldoon was born in County Armagh, in Northern Ireland, in 1951. He is the eldest of three children. His mother was a primary schoolteacher and his father held many jobs, including mushroom cultivator. Muldoon attended Queen’s University from 1969 to 1973, and remained in Belfast until 1986, working as a radio and television producer for the BBC. He has lived in the United States since 1987 and is presently Howard G. B. Clark ’21 Professor in the Humanities at Princeton University. Additionally, in 1999 he was elected to the five-year term of Professor of Poetry at the University of Oxford.

Muldoon has been called a precocious talent. When he is profiled in newspapers, one of three anecdotes invariably makes the lead: The story that as a child he made a project of The Junior World Encyclopedia, which he calls “a terrific read from the aardvark on,” for lack of much apart from religious tracts and school primers at home. Or the story that, some time before he was asked to join the Group, the Dublin critical society, the young poet approached Seamus Heaney with a batch of his work, wondering what he could do to improve it. Heaney famously replied, “Nothing.” Or the simple fact that Faber and Faber published Muldoon’s first book, New Weather (1973), while he was still an undergraduate. His subsequent volumes are Mules (1977), Why Brownlee Left (1980), Quoof (1983), Meeting the British (1987), Madoc: A Mystery (1990), The Annals of Chile (1994), and Hay (1998). These books are collected in Poems 1968–1998 (2001). Muldoon’s most recent volume is Moy Sand and Gravel (2002), for which he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry. As well as translating the work of contemporary Irish poets, Muldoon has published several books for children and collaborated with the composer Daron Hagen on several operas.

The perceived difficulty of Muldoon’s work is considered to have culminated in Madoc: A Mystery and The Annals of Chile, the first books he published after his move to the United States, and through which, to a greater or lesser extent, he dramatizes that relocation. In the book-length poem “Madoc,” Muldoon supposes that Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey took up their (actual) fancy of founding a Pantisocratic community in North America. Each short section of the poem is named for a philosopher; in fits and starts—by puns, the rare diagram, and the odd snippet of coherent narrative—the reader becomes aware of a Western adventure taking shape. Some have suggested the two protagonists stand for Muldoon and Heaney, embarking on careers inside the American Academy. The work prompted John Banville, writing in The New York Review of Books, to remark of Muldoon, for whom he otherwise expressed admiration, “I cannot help feeling that this time he has gone too far.” In “The Annals of Chile” Muldoon develops further the long-form pseudo-autobiography, imagining the life his father might have led, and the life of the son he might have fathered, had Muldoon Sr. left Ireland for Argentina as a young man, a notion he had toyed with. Muldoon once said that he hoped readers would “be moved by it, both to tears and laughter.” Indeed the poetry, riddled with etymological puns, obscure references, shaggy dogs, and half-truths, can seem on the surface to mock everything, even while it calls up intense feeling. (When Muldoon cheerfully points out which poems of his one might consider doggerel—“As,” for example—he frees up his readers’ critical faculties for a whole other feast of delights. On the other hand, this can reinforce the suspicion that, elsewhere, we’re missing the point.)

Some readers have taken Muldoon’s playfulness as an affront to scholarship, and certainly some take it as an affront to their own intelligence. But to these complaints Muldoon justifiably counters that his kind of literary gaming requires of readers what contemporary film requires of its audience—a familiarity with the medium’s history and tricks that we can take more or less for granted.

This interview was begun at Muldoon’s office at Princeton, in a modern building that houses several other arts faculties. Muldoon keeps a tidy desk facing bookcases on three walls, and the door in the corner of the U; pushed up against the shelves are a dozen wooden chairs to accommodate student workshops. The complete OED is shelved in a cabinet beside the desk. On top of the cabinet stand a photograph of the novelist Jean Korelitz, Muldoon’s wife of fifteen years, and a bronze bust of the poet himself, looking jaunty and almost anonymous under a Princeton baseball cap. In a narrow space on one wall hangs a pale blue page in a beat-up frame: an application of incorporation of the Irish National Theater Society, signed by William Butler Yeats. Other hangings include a handwritten poem by Seamus Heaney addressed to Muldoon; an antique map of County Armagh and a drawing of the town of Oxford; a poster-sized blowup of the cover of Madoc: A Mystery; editions of Muldoon’s poems that have appeared on subway cars in Dublin, London, and New York; and both a photo and a cartoon of Heaney and Muldoon together. We sat in front of the desk in a couple of low-slung armchairs next to a sunburst Fender Stratocaster set on a guitar stand. There were frequent distractions. The radiator. A student with copies of — to autograph. Inquiries delivered by e-mail, phone, and in person as to the weather. (The end-of-term Muldoon-Korelitz garden party was scheduled for the following afternoon. Eventually it was put off a day—without complete confidence: “It’s in the hands of the gods. And we know what they’re like.”)

At four o’clock we left the office for Muldoon’s home, once a tavern (“The Black Horse” of the poems). Stopping on the way to pick up groceries, his four-year-old son, Asher, from school, and so on, Muldoon punctuated our conversation with high-pitched horse’s whinnies. Home is an airy clapboard house built high on a bank of the Raritan Canal, surrounded on all sides by greenery. The rooms are low ceilinged, dark, and breezy, decorated with wooden furniture and secondhand genre paintings and portraits. We resumed our conversation first in one room, then another, then another, as the Korelitz-Muldoons (last of all, but not least, Dorothy, ten, and five or six dogs and cats) tumbled around in anticipation of a housebound Saturday. In conversation, Muldoon’s keen focus is diffused with an improvisatory brio. Talking can be a pleasure.

INTERVIEWER

To begin at the beginning, what do you remember of your childhood in Armagh?

PAUL MULDOON

Armagh was a peasant society that really had not changed for a long time. I remember vividly a neighbor plowing with horses, people planting turnips with a turnip barrow. There were tramps, gentlemen of the road. One of them was called Paddy Patch, and there was one called Forty Coats, because he wore so many layers. Layers are the secret, you know.

I’m still very conscious of coming from a society where storytelling was much prized and praised. I was reminded the other day that the Celts had a god of eloquence by the name of Ogmios. Ogmios was still lurking in the back of the minds of my neighbors. They loved poems, songs, good stories. And still do.

My earliest memories are of a place called Eglish, where my father ran a tiny little shop, a subterranean place with a bench. I remember running towards the shop and expecting the door to be solid, but going through it and then falling into the shop. In “The Right Arm” I write about the various items for sale there, including a dreadful confection called clove rock kept in a glass jar.

INTERVIEWER

At the end of “The Right Arm” you say you’re still waiting for that jar to break. Are your childhood memories still vivid?

MULDOON

Absolutely. I do feel very much that I can be in that moment, almost at will. It takes almost nothing to get me back there, certainly to the house I was brought up in, after the age of four, near a village called the Moy. The room I had there was a bedroom-cum-workroom looking on to a little backyard with a house, that my father had built, used mostly for pigs.

INTERVIEWER

Lots of pigs?

MULDOON

A litter—twelve or fifteen. I’m a great fan of the pig, I have to say. I used to go out there on a cold winter morning and the pigs were being fed, and it was quite appetizing, to see them eating their porridge.

INTERVIEWER

Did you eat any of them?

MULDOON

No, those were sold at the market, but I have a memory of a pig killer coming to the house we’d lived in before—“Ned Skinner” is based somewhat on that experience. That day certainly we ate our own pigs, or parts of them. There were always various animals lurking around—turkeys, chickens, dogs, cats, hamsters, tortoises.

INTERVIEWER

Hedgehogs?

MULDOON

The hedgehog wasn’t a pet, of course—I’m not sure if some of the others were pets, either. The hedgehog used to come round to the back door, for maybe a year, for its bedtime saucer of milk. The hedgehog was the inspiration, as it were, for one of the first poems I wrote.

INTERVIEWER

It appeared in your first book, New Weather. How about even earlier work, juvenilia?

MULDOON

I’m not sure where juvenilia begins and ends; I may not be out of that phase. I may not want to be out of it. The earlier poems were written very much in the style of T. S. Eliot. I managed to get myself out of that somehow, miraculously. Partly there was no future in it. I don’t mean in terms of eternity, just that no one is going to do anything of interest if he or she is writing sub-Eliot.

INTERVIEWER

How did it feel to discover your own voice?

MULDOON

I don’t know if I’ve ever found a voice. In fact, I’m rather skeptical of that idea having any currency. Each poem demands its own particular voice. It’s not as if one size fits all. Certainly not the kinds of poem I’m interested in writing. But I suppose in “Hedgehog” something of its own—not my own—might have happened.