Issue 46, Spring 1969

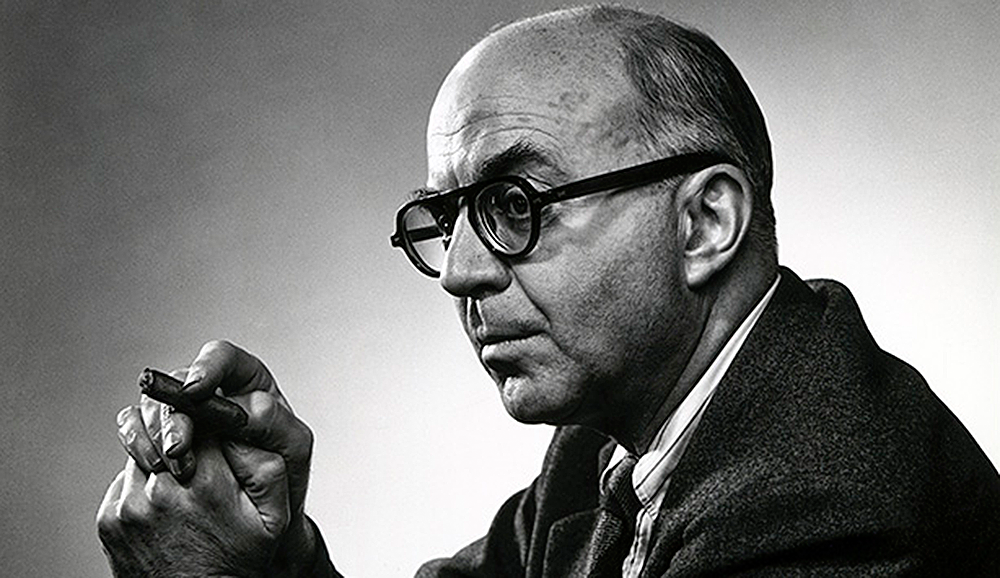

John Dos Passos.

John Dos Passos.

Shortly after John Dos Passos had completed the three volumes of U.S.A. in 1936, Jean-Paul Sartre observed that he was “the greatest writer of our time.” In 1939, a New Masses reviewer attacked his novel, Adventures of a Young Man, as “Trotskyist agitprop.” Neither statement set a pattern for later estimates of Dos Passos, although they suggested the extremes with which his earlier novels (Three Soldiers, Manhattan Transfer, and U.S.A.) and then his later ones (District of Columbia, Midcentury) have been accepted. Dos Passos has also run to extremes in his experiences: from the New Masses to the National Review, from the Norton-Harjes Ambulance Service to an assignment for Life in the Pacific Theater, from Versailles to Nuremberg, from incessant travel to the quiet of his grandfather’s farm.

Despite all these contradictions and despite even the autobiographical thread in his work, he has been a writer of unusual detachment. He is still asked, as he was in the twenties: “Are you for us or against us?” He has also been unusually industrious, having published eighteen books since U.S.A. He works too hard and too steadily to spare much time for answering questions about himself.

Dos Passos was interviewed in 1968 on his farm, Spence’s Point, on the Northern Neck of Virginia, a sandy, piney strip of land between the Rappahannock and the Potomac. The state highway in from U.S. 301 passes turnoffs to the birthplaces of Washington and Monroe. The windy, overcast June day didn’t hold enough threat of a storm to keep the writer, his strikingly handsome wife, and the interviewer from swimming in the Potomac before proceeding to anything else. He spoke easily about what he was doing currently or was soon about to do but turned talk away from what he had done years before by short, muffled answers, a nod or chuckle, and a quick switch back to fishing in the Andes and flying down the Amazon from Iquitos. The interview took place in a small parlor of the late eighteenth-century house.

He is a tall man, conspicuously fit. He is round-faced, bald, wears steel-rimmed glasses, and is much younger than he appears to be in recent photographs. Characteristically, his head is pitched forward at a slight angle in an attitude of perpetual attention. He speaks a little nervously and huskily, with a trace of the cultivated accent his schoolmates once thought “foreign.” Although it seemed that nothing could ruffle his natural courtesy, he was uncomfortable about what he called “enforced conversation.” The tape recorder had something to do with this, but it was more obvious that he simply did not enjoy talking about himself. Hesitations aside, he was completely willing to say exactly what he thought about individuals and events.

INTERVIEWER

Is this the same farm where you spent your summers as a boy?

JOHN DOS PASSOS

This is a different part of the same farm. When my father was alive, we had a house down at the other end, a section that has been sold, which is now part of a little development called Sandy Point, that string of cottages you saw along the shore. We’ve been here for more than ten years now, but I don’t get to spend as much time here as I would like to because I still have a good deal of unfinished traveling.

INTERVIEWER

Has this polarity between Spence’s Point and your traveling had any particular effect on your writing?

DOS PASSOS

I don’t know. Of course anything that happens to you has some bearing upon what you write.

INTERVIEWER

Perhaps it once led you to write that the novelist was a truffle dog going ahead of the social historian?

DOS PASSOS

I don’t know how true that is. It’s the hardest thing in the world to talk about your own work. You stumble along, and often the truffle dog doesn’t get to eat the truffle … he just picks it up.

INTERVIEWER

Have you become the social historian at the expense of the artist?

DOS PASSOS

There’s just no way that I can tell. I have to do what I’m interested in at the time, and I don’t think there’s anything necessarily inartistic about being the historian. I have great admiration for good history. All of my work has some certain historical connotation. Take Three Soldiers. I was trying to record something that was going on. I always felt that it might not be any good as a novel, but that it would at least be useful to add to the record. I had that idea when I began writing—with One Man’s Initiation—and I’ve had it right along.

INTERVIEWER

Always, then, you have been observing for the record?

DOS PASSOS

Very much, I think.

INTERVIEWER

It must have been difficult to remain simply an objective observer.

DOS PASSOS

Possibly, but I think I’ve tended to come back to center. I’m often carried away by emotions and enthusiasms for various ideas at one time or another, but I think the desire to observe, to put down what you see as accurately as possible, is still paramount. I think the critics never understand that because they always go on the basis that if a man writes about Mormonism he must be a Mormon, that if he writes about Communism he must be Communist, which is not necessarily true. I’ve usually been on the fence in partisan matters. I’ve often been partisan for particular people, usually people who seem to be getting a raw deal, but that’s a facet I share with many others.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve said that when you began observing you were a “half-baked young man” out of Harvard. Have you had any recent thoughts about that education?

DOS PASSOS

I got quite a little out of being at Harvard, although I was kicking all of the time I was there, complaining about the “ethercone” atmosphere I described in camera eye. I probably wouldn’t have stayed if it hadn’t been for my father, who was anxious for me to go through. At that time, the last of the old New Englanders were still at Harvard. They were really liberal-minded people, pretty thoroughly independent in their ideas, and they all had a sort of basic Protestant ethic behind them. They really knew what was what. I didn’t agree with them then, but looking back on them now, I think more highly of them than I once did. But that essentially valid cast of mind was very much damaged by the strange pro-Allied and anti-German delusion that swept through them. You couldn’t talk to people about it. When the war started in the summer of my sophomore year, I was curious to see it, even though theoretically I disapproved of war as a human activity. I was anxious to see what it was like. Like Charley Anderson in 42nd Parallel, I wanted to go over before everything “went belly-up.” When I got out of college in the summer of 1916, I was anxious to get started in architecture, but at the same time I was so restless that I had already managed to sign myself up in the volunteer ambulance service. My father was determined to put that off, so we kind of compromised on a Spanish expedition, and I went to Madrid to study architecture. Then my father died in January of 1917, and I went ahead into the ambulance service. I suppose that World War I then became my university.