Issue 44, Fall 1968

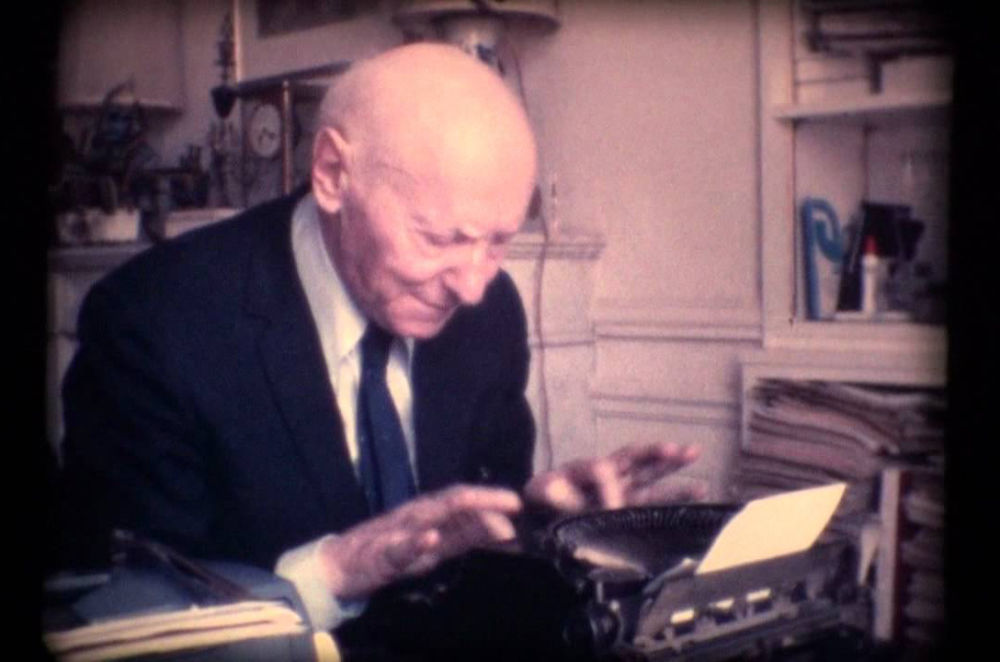

Video still of Isaac Bashevis Singer, by Tetsuo Kogawa, 1977.

Video still of Isaac Bashevis Singer, by Tetsuo Kogawa, 1977.

Isaac Bashevis Singer lives with his second wife in a large, sunny five-room apartment in an Upper Broadway apartment house. In addition to hundreds of books and a large television set, it is furnished with the kind of pseudo-Victorian furniture typical of the comfortable homes of Brooklyn and the Bronx in the 1930s.

Singer works at a small, cluttered desk in the living room. He writes every day, but without special hours—in between interviews, visits, and phone calls. His name is still listed in the Manhattan telephone directory, and hardly a day goes by without his receiving several calls from strangers who have read something he has written and want to talk to him about it. Until recently, he would invite anyone who called for lunch, or at least coffee.

Singer writes his stories and novels in lined notebooks, in longhand, in Yiddish. Most of what he writes still appears first in the Jewish Daily Forward, America’s largest Yiddish-language daily, published in New York City. Getting translators to put his work into English has always been a major problem. He insists on working very closely with his translators, going over each word with them many times.

Singer always wears dark suits, white shirts, and dark ties. His voice is high but pleasant, and never raised. He is of medium height, thin, and has an unnaturally pale complexion. For many years he has followed a strict vegetarian diet.

The first impression Singer gives is that he is a fragile, weak man who would find it an effort to walk a block. Actually, he walks fifty to sixty blocks a day, a trip that invariably includes a stop to feed pigeons from a brown paper bag. He loves birds and has two pet parakeets who fly about his apartment uncaged.

INTERVIEWER

Many writers when they start out have other writers they use as models.

ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER

Well, my model was my brother, I. J. Singer, who wrote The Brothers Ashkenazi. I couldn’t have had a better model than my brother. I saw him struggle with my parents and I saw how he began to write and how he slowly developed and began to publish. So naturally he was an influence. Not only this, but in the later years before I began to publish, my brother gave me a number of rules about writing which seem to me sacred. Not that these rules cannot be broken once in a while, but it’s good to remember them. One of his rules was that while facts never become obsolete or stale, commentaries always do. When a writer tries to explain too much, to psychologize, he’s already out of time when he begins. Imagine Homer explaining the deeds of his heroes according to the old Greek philosophy, or the psychology of his time. Why, nobody would read Homer! Fortunately, Homer just gave us the images and the facts, and because of this the Iliad and the Odyssey are fresh in our time. And I think this is true about all writing. Once a writer tries to explain what the hero’s motives are from a psychological point of view, he has already lost. This doesn’t mean that I am against the psychological novel. There are some masters who have done it well. But I don’t think it is a good thing for a writer, especially a young writer, to imitate them. Dostoyevsky, for example. If you can call him a writer of the psychological school; I’m not sure I do. He had his digressions and he tried to explain things in his own way, but even with him his basic power is in giving the facts.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think of psychoanalysis and writing? Many writers have been psychoanalyzed and feel this has helped them to understand not only themselves but the characters they write about.

SINGER

If the writer is psychoanalyzed in a doctor’s office, that is his business. But if he tries to put the psychoanalysis into the writing, it’s just terrible. The best example is the one who wrote Point Counter Point. What was his name?

INTERVIEWER

Aldous Huxley.

SINGER

Aldous Huxley. He tried to write a novel according to Freudian psychoanalysis. And I think he failed in a bad way. This particular novel is now so old and so stale that even in school it cannot be read anymore. So, I think that when a writer sits down and he psychoanalyzes, he’s ruining his work.

INTERVIEWER

You once told me that the first piece of fiction you ever read was the Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

SINGER

Well, I read these things when I was a boy of ten or eleven, and to me they looked so sublime, so wonderful, that even today I don’t dare to read Sherlock Holmes again because I am afraid that I may be disappointed.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think A. Conan Doyle influenced you in any way?

SINGER

Well, I don’t think that the stories of Sherlock Holmes had any real influence on me. But I will say one thing—from my childhood I have always loved tension in a story. I liked that a story should be a story. That there should be a beginning and an end, and there should be some feeling of what will happen at the end. And to this rule I keep today. I think that storytelling has become in this age almost a forgotten art. But I try my best not to suffer from this kind of amnesia. To me a story is still a story where the reader listens and wants to know what happens. If the reader knows everything from the very beginning, even if the description is good, I think the story is not a story.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think about the Nobel Prize for literature going to S. Y. Agnon and Nelly Sachs?

SINGER

About Nelly Sachs, I know nothing, but I know Agnon. Since I began to read. And I think he’s a good writer. I wouldn’t call him a genius, but where do you get so many geniuses nowadays? He’s a solid writer of the old school, a school which loses a lot in translation. But as far as Hebrew is concerned, his style is just wonderful. Every work of his is associated with the Talmud and the Bible and the Midrash. Everything he writes has many levels, especially to those who know Hebrew. In translation, all of these other levels disappear and there is only the pure writing, but then that is also good.

INTERVIEWER

The prize committee said that they were giving the Nobel Prize to two Jewish writers who reflected the voice of Israel. That leads me to wonder how you would define a Jewish writer as opposed to a writer who happens to be Jewish?

SINGER

To me there are only Yiddish writers, Hebrew writers, English writers, Spanish writers. The whole idea of a Jewish writer, or a Catholic writer, is kind of far-fetched to me. But if you forced me to admit that there is such a thing as a Jewish writer, I would say that he would have to be a man really immersed in Jewishness, who knows Hebrew, Yiddish, the Talmud, the Midrash, the Hasidic literature, the Cabbala, and so forth. And then if in addition he writes about Jews and Jewish life, perhaps then we can call him a Jewish writer, whatever language he writes in. Of course, we can also call him just a writer.

INTERVIEWER

You write in Yiddish, which is a language very few people can read today. Your books have been translated into fifty-eight different languages, but you have said you are bothered by the fact that most of your readers, the vast majority of your readers, have to read you in translation, whether it’s English or French. That very few writers can read you in Yiddish. Do you feel that a lot is lost in translation?

SINGER

The fact that I don’t have as many readers in Yiddish as I would have liked to have bothers me. It’s not good that a language is going downhill instead of up. I would like Yiddish to bloom and flower just as the Yiddishists say it does bloom and flower. But as far as translation is concerned, naturally every writer loses in translation, particularly poets and humorists. Also writers whose writing is tightly connected to folklore are heavy losers. In my own case, I think I am a heavy loser. But then lately I have assisted in the translating of my works, and knowing the problem, I take care that I don’t lose too much. The problem is that it’s very hard to find a perfect equivalent for an idiom in another language. But then it’s also a fact that we all learned our literature through translation. Most people have studied the Bible only in translation, have read Homer in translation, and all the classics. Translation, although it does do damage to an author, it cannot kill him: if he’s really good, he will come out even in translation. And I have seen it in my own case. Also, translation helps me in a way. Because I go through my writings again and again while I edit the translation and work with the translator, and while I am doing this I see all the defects of my writing. Translation has helped me avoid pitfalls which I might not have avoided if I had written the work in Yiddish and published it and not been forced because of the translation to read it again.

INTERVIEWER

Is it true that for five years you stopped writing entirely because you felt there was nobody to write for?

SINGER

It is true that when I came to this country I stopped writing for a number of years. I don’t know exactly if it was because I thought there were no readers. There were many readers. Coming from one country to another, immigrating, is a kind of a crisis. I had a feeling that my language was so lost. My images were not anymore. Things—I saw thousands of objects for which I had no name in Yiddish in Poland. Take such a thing as the subway—we didn’t have a subway in Poland. And we didn’t have a name for it in Yiddish. Suddenly I had to do with a subway and with a shuttle train and a local, and my feeling was that I lost my language and also my feeling about the things which surrounded me. Then, of course, there was the trouble of making a living and adjusting myself to the new surroundings … all of this worked so that for a number of years I couldn’t write.