Issue 43, Summer 1968

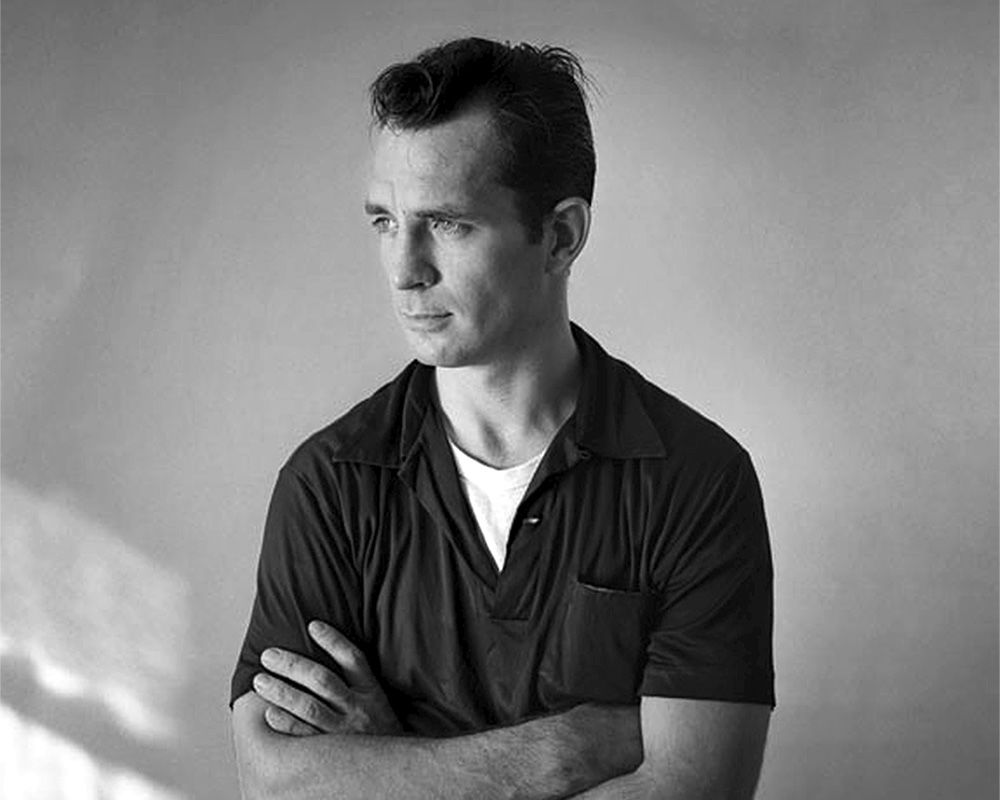

Jack Kerouac, ca. 1956. Photograph by Tom Palumbo

Jack Kerouac, ca. 1956. Photograph by Tom Palumbo

The Kerouacs have no telephone. Ted Berrigan had contacted Kerouac some months earlier and had persuaded him to do the interview. When he felt the time had come for their meeting to take place, he simply showed up at the Kerouacs’s house. Two friends, poets Aram Saroyan and Duncan McNaughton, accompanied him. Kerouac answered his ring; Berrigan quickly told him his name and the visit’s purpose. Kerouac welcomed the poets, but before he could show them in, his wife, a very determined woman, seized him from behind and told the group to leave at once.

“Jack and I began talking simultaneously, saying ‘Paris Review!’ ‘Interview!’ etc.,” Berrigan recalls, “while Duncan and Aram began to slink back toward the car. All seemed lost, but I kept talking in what I hoped was a civilized, reasonable, calming, and friendly tone of voice, and soon Mrs. Kerouac agreed to let us in for twenty minutes, on the condition that there be no drinking.

“Once inside, as it became evident that we actually were in pursuit of a serious purpose, Mrs. Kerouac became more friendly, and we were able to commence the interview. It seems that people still show up constantly at the Kerouacs’s looking for the author of On the Road, and stay for days, drinking all the liquor and diverting Jack from his serious occupations.

“As the evening progressed the atmosphere changed considerably, and Mrs. Kerouac, Stella, proved a gracious and charming hostess. The most amazing thing about Jack Kerouac is his magic voice, which sounds exactly like his works. It is capable of the most astounding and disconcerting changes in no time flat. It dictates everything, including this interview.

“After the interview, Kerouac, who had been sitting throughout the interview in a President Kennedy-type rocker, moved over to a big poppa chair and said, ‘So you boys are poets, hey? Well, let’s hear some of your poetry.’ We stayed for about an hour longer and Aram and I read some of our things. Finally, he gave each of us a signed broadside of a recent poem of his, and we left.”

INTERVIEWER

Could we put the footstool over here to put this on?

STELLA

Yes.

JACK KEROUAC

God, you’re so inadequate there, Berrigan.

INTERVIEWER

Well, I’m no tape-recorder man, Jack. I’m just a big talker, like you. OK, we’re off.

KEROUAC

Okay? [Whistles.] Okay?

INTERVIEWER

Actually I’d like to start ... The first book I ever read by you, oddly enough, since most people first read On the Road ... the first one I read was The Town and the City ...

KEROUAC

Gee!

INTERVIEWER

I checked it out of the library ...

KEROUAC

Gee! Did you read Doctor Sax? Tristessa?

INTERVIEWER

You better believe it. I even read Rimbaud. I have a copy of Visions of Cody that Ron Padgett bought in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

KEROUAC

Screw Ron Padgett! You know why? He started a little magazine called White Dove Review in Kansas City, was it? Tulsa? Oklahoma ... yes. He wrote, “Start our magazine off by sending us a great big poem.” So I sent him “The Thrashing Doves.” And then I sent him another one and he rejected the second one because his magazine was already started. That’s to show you how punks try to make their way by scratching down on a man’s back. Aw, he’s no poet. You know who’s a great poet? I know who the great poets are.

INTERVIEWER

Who?

KEROUAC

Let’s see, is it ... William Bissett of Vancouver. An Indian boy. Bill Bissett, or Bissonnette.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s talk about Jack Kerouac.

KEROUAC

He’s not better than Bill Bissett, but he’s very original.

INTERVIEWER

Why don’t we begin with editors. How do you ...

KEROUAC

OK. All my editors since Malcolm Cowley have had instructions to leave my prose exactly as I wrote it. In the days of Malcolm Cowley, with On the Road and The Dharma Bums, I had no power to stand by my style for better or for worse. When Malcolm Cowley made endless revisions and inserted thousands of needless commas like, say, “Cheyenne, Wyoming” (why not just say “Cheyenne Wyoming” and let it go at that, for instance), why, I spent five hundred dollars making the complete restitution of the Bums manuscript and got a bill from Viking Press called “Revisions.” Ha ho ho. And so you asked about how do I work with an editor ... well nowadays I am just grateful to him for his assistance in proofreading the manuscript and in discovering logical errors, such as dates, names of places. For instance, in my last book I wrote Firth of Forth then looked it up, on the suggestion of my editor, and found that I’d really sailed off the Firth of Clyde. Things like that. Or I spelled Aleister Crowley “Alisteir,” or he discovered little mistakes about the yardage in football games ... and so forth. By not revising what you’ve already written you simply give the reader the actual workings of your mind during the writing itself: you confess your thoughts about events in your own unchangeable way ... Well, look, did you ever hear a guy telling a long wild tale to a bunch of men in a bar and all are listening and smiling, did you ever hear that guy stop to revise himself, go back to a previous sentence to improve it, to defray its rhythmic thought impact. ... If he pauses to blow his nose, isn’t he planning his next sentence? And when he lets that next sentence loose, isn’t it once and for all the way he wanted to say it? Doesn’t he depart from the thought of that sentence and, as Shakespeare says, “forever holds his tongue” on the subject, since he’s passed over it like a part of a river that flows over a rock once and for all and never returns and can never flow any other way in time? Incidentally, as for my bug against periods, that was for the prose in October in the Railroad Earth, very experimental, intended to clack along all the way like a steam engine pulling a one-hundred-car freight with a talky caboose at the end, that was my way at the time and it still can be done if the thinking during the swift writing is confessional and pure and all excited with the life of it. And be sure of this, I spent my entire youth writing slowly with revisions and endless rehashing speculation and deleting and got so I was writing one sentence a day and the sentence had no FEELING. Goddamn it, FEELING is what I like in art, not CRAFTINESS and the hiding of feelings.