Issue 42, Winter-Spring 1968

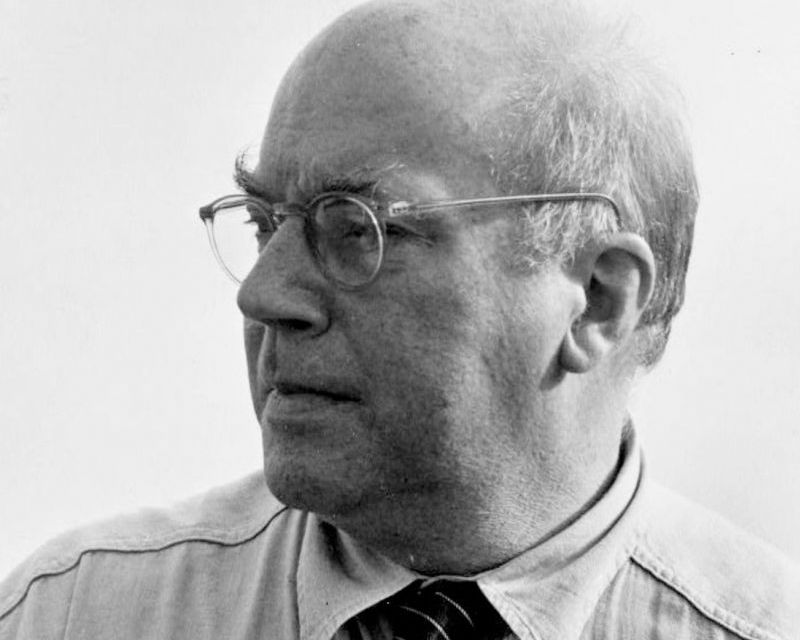

Conrad Aiken.

Conrad Aiken.

The interview took place in two sessions of about an hour each in September 1963, at Mr. Aiken’s house in Brewster, Massachusetts. The house, called Forty-one Doors, dates largely from the eighteenth century; a typical old Cape Cod farmhouse, the rooms are small but many, opening in all directions off what must originally have been the most important room, the kitchen. The house is far enough from the center of town to be reasonably quiet even at the height of the summer, and it is close enough to the north Cape shore for easy trips to watch the gulls along the edges of relatively unspoiled inlets.

Mr. Aiken dresses typically in a tweed sports coat, a wool or denim shirt, and a heavy wool tie. A fringe of sparse white hair gives him a curiously friarly appearance, belied by his irreverence and love of bawdy puns.

He answered the questions about his own work seriously and carefully but did not appear to enjoy them; not that he seemed to find them too pressing or impertinent, rather as if answering them was simply hard work. He enjoyed far more telling anecdotes about himself and his friends and chuckled frequently in recalling these stories.

By the end of each hour Mr. Aiken, who had been seriously ill the previous winter, was visibly tired; but once the tape recorder was stilled and the martinis mixed and poured into silver cups—old sculling or tennis trophies retrieved from some pawn or antique shop—he quickly revived. He was glad to be interviewed, but more glad still when it was over.

Later, shortly before the interview went to press, a dozen or so follow-up questions were sent to him at the Cape; the answers to these are spliced into the original interview. “You may find you will need to do a bit of dovetailing here and there,” he wrote; “the old mens isn’t quite, may never be, as sana as before, if indeed it ever was.” But there was no real problem; his mind and memory remain clear and precise despite the physical frailties that age has brought.

INTERVIEWER

In Ushant you say that you decided to be a poet when you were very young—about six years old, I think.

CONRAD AIKEN

Later than that. I think it was around nine.

INTERVIEWER

I was wondering how this resolve to be a poet grew and strengthened?

AIKEN

Well, I think Ushant describes it pretty well, with that epigraph from Tom Brown’s School Days: “I’m the poet of White Horse Vale, sir, with Liberal notions under my cap!” For some reason those lines stuck in my head, and I’ve never forgotten them. This image became something I had to be.

INTERVIEWER

While you were at Harvard, were you constantly aware that you were going to be a poet; training yourself in most everything you studied and did?

AIKEN

Yes. I compelled myself all through to write an exercise in verse, in a different form, every day of the year. I turned out my page every day, of some sort—I mean I didn’t give a damn about the meaning, I just wanted to master the form—all the way from free verse, Walt Whitman, to the most elaborate of villanelles and ballad forms. Very good training. I’ve always told everybody who has ever come to me that I thought that was the first thing to do. And to study all the vowel effects and all the consonant effects and the variation in vowel sounds. For example, I gave Malcolm Lowry an exercise to do at Cuernavaca, of writing ten lines of blank verse with the caesura changing one step in each line. Going forward, you see, and then reversing on itself.

INTERVIEWER

How did Lowry take to these exercises?

AIKEN

Superbly. I still have a group of them sent to me at his rented house in Cuernavaca, sent to me by hand from the bar with a request for money, and in the form of a letter—and unfortunately not used in his collected letters; very fine, and very funny. As an example of his attention to vowel sounds, one line still haunts me: “Airplane or aeroplane, or just plain plane.” Couldn’t be better.

INTERVIEWER

What early readings were important to you? I gather that Poe was.

AIKEN

Oh, Poe, yes. I was reading Poe when I was in Savannah, when I was ten, and scaring myself to death. Scaring my brothers and sisters to death, too. So I was already soaked in him, especially the stories.

INTERVIEWER

I see you listed occasionally as a Southern writer. Does this make any sense to you?

AIKEN

Not at all. I’m not in the least Southern; I’m entirely New England. Of course, the Savannah ambiente made a profound impression on me. It was a beautiful city and so wholly different from New England that going from South to North every year, as we did in the summers, provided an extraordinary counterpoint of experience, of sensuous adventure. The change was so violent, from Savannah to New Bedford or Savannah to Cambridge, that it was extraordinarily useful. But no, I never was connected with any of the Southern writers.

INTERVIEWER

In what way was the change from Savannah to New England “useful” to you?

AIKEN

Shock treatment, I suppose: the milieu so wholly different, and the social customs, and the mere transplantation; as well as having to change one’s accent twice a year—all this quite apart from the astonishing change of landscape. From swamps and Spanish moss to New England rocks.

INTERVIEWER

What else at Harvard was important to your development as a poet, besides the daily practice you described?

AIKEN

I’m afraid I wasn’t much of a student, but my casual reading was enormous. I did have some admirable courses, especially two years of English 5 with Dean Briggs, who was a great teacher, I think, and that was the best composition course I ever had anywhere.

INTERVIEWER

How did Briggs go about teaching writing?

AIKEN

He simply let us write, more or less, what we wanted to. Then discussion (after his reading aloud of a chosen specimen) and his own marvelous comments: He had genius, and emanated it. Then, at the end of class, we had ten minutes in which to write a short critique of the piece that had been read. This was so helpful to me that I took the course for two years.

INTERVIEWER

Was Copeland still teaching then? What did you think of him?

AIKEN

Brilliant reader, not a profound teacher. Vain. At the end of the year he asked me, Aiken, do you think this course has benefited you? I was taken aback and replied, Well, it has made me write often. He replied, Aiken, you’re a very dry young man.