Issue 30, Summer-Fall 1963

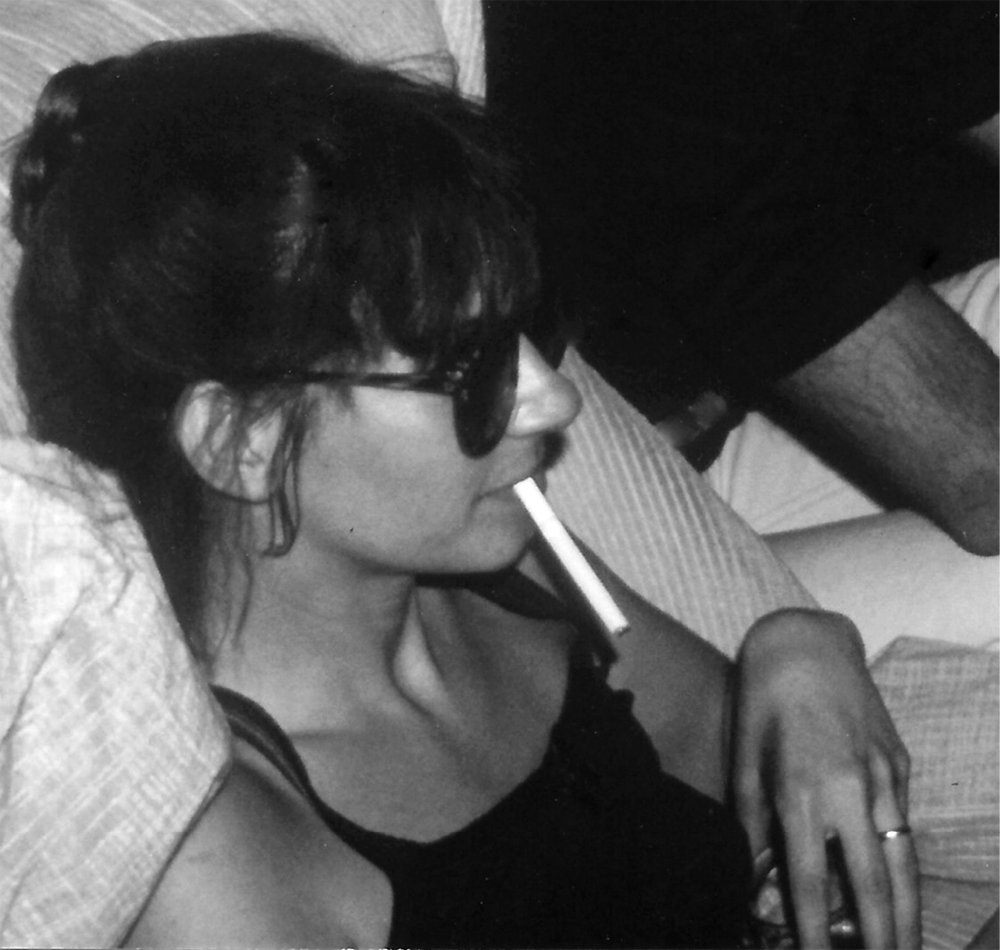

Evelyn Waugh, photograph by Carl Van Vechten.

Evelyn Waugh, photograph by Carl Van Vechten.

The interview which follows is the result of two meetings on successive days at the Hyde Park Hotel, London, during April 1962.

I had written to Mr. Waugh earlier asking permission to interview him, and in this letter I had promised that I should not bring a tape recorder with me. I imagined, from what he had written in the early part of The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, that he was particularly averse to them.

We met in the hall of the hotel at three in the afternoon. Mr. Waugh was dressed in a dark-blue suit with a heavy overcoat and a black homburg hat. Apart from a neatlytied, small, brown-paper parcel, he was unencumbered. After we had shaken hands and he had explained that the interview would take place in his own room, the first thing he said was, “Where is your machine?”

I explained that I hadn't brought one.

“Have you sold it?” he continued as we got into the lift. I was somewhat nonplussed. In fact, I had at one time owned a tape recorder, and I had indeed sold it three years earlier, before going to live abroad. None of this seemed very relevant. As we ascended slowly, Mr. Waugh continued his cross-questioning about the machine. How much had I bought it for? How much had I sold it for? Whom did I sell it to?

“Do you have shorthand, then?” he asked as we left the lift.

I explained that I did not.

“Then it was very foolhardy of you to sell your machine, wasn't it?”

He showed me into a comfortable, soberly furnished room, with a fine view over the trees across Hyde Park. As he moved about the room he repeated twice under his breath, “The horrors of London life! The horrors of London life!”

“I hope you won't mind if I go to bed,” he said, going into the bathroom. From there he gave me a number of comments and directions:

“Go and look out of the window. This is the only hotel with a civilized view left in London . . .. Do you see a brown-paper parcel? Open it, please.”

I did so.

“What do you find?”

“A box of cigars.”

“Do you smoke?”

“Yes. I am smoking a cigarette now.”

“I think cigarettes are rather squalid in the bedroom. Wouldn't you rather smoke a cigar?”

He reentered, wearing a pair of white pajamas and metal-rimmed spectacles. He took a cigar, lit it, and got into bed.

I sat down in an armchair at the foot of the bed, juggling notebook, pen, and enormous cigar between hands and knees.

“I shan't be able to hear you there. Bring up that chair.” He indicated one by the window, so I rearranged my paraphernalia as we talked of mutual friends. Quite soon he said, “When is the inquisition to begin?”

I had prepared a number of lengthy questions—the reader will no doubt detect the shadows of them in what follows—but I soon discovered that they did not, as I had hoped, elicit long or ruminative replies. Perhaps what was most striking about Mr. Waugh's conversation was his command of language: his spoken sentences were as graceful, precise, and rounded as his written sentences. He never faltered, nor once gave the impression of searching for a word. The answers he gave to my questions came without hesitation or qualification, and any attempt I made to induce him to expand a reply generally resulted in a rephrasing of what he had said before.

I am well aware that the result on the following pages is unlike the majority of Paris Review interviews; first it is very much shorter, and secondly, it is not “an interview in depth.” Personally, I believe that Mr. Waugh did not lend himself, either as a writer or as a man, to the form of delicate psychological probing and self-analysis which are characteristic of many of the other interviews. He would consider impertinent an attempt publicly to relate his life and his art, as was demonstrated conclusively when he appeared on an English television program, “Face to Face,” some time ago and parried all such probing with brief, flat, and, wherever possible, monosyllabic replies.

However, I should like to do something to dismiss the mythical image of Evelyn Waugh as an ogre of arrogance and reaction. Although he carefully avoided taking part in the marketplace of literary life, of conferences, prize giving, and reputation building, he was, nonetheless, both well informed and decided in his opinions about his contemporaries and juniors. Throughout the three hours I spent with him he was consistently helpful, attentive, and courteous, allowing himself only minor flights of ironic exasperation if he considered my questions irrelevant or ill-phrased.

INTERVIEWER

Were there attempts at other novels before Decline and Fall?

EVELYN WAUGH

I wrote my first piece of fiction at seven: The Curse of the Horse Race. It was vivid and full of action. Then, let's see, there was The World to Come, written in the meter of Hiawatha. When I was at school I wrote a five-thousand-word novel about modern school life. It was intolerably bad.

INTERVIEWER

Did you write a novel at Oxford?

WAUGH

No. I did sketches and that sort of thing for the Cherwell and for a paper Harold Acton edited—Broom, it was called. The Isis was the official undergraduate magazine: it was boring and hearty, written for beer drinkers and rugger players. The Cherwell was a little more frivolous.

INTERVIEWER

Did you write your life of Rossetti at that time?

WAUGH

No. I came down from Oxford without a degree, wanting to be a painter. My father settled my debts and I tried to become a painter. I failed as I had neither the talent nor the application—I didn't have the moral qualities.

INTERVIEWER

Then what?

WAUGH

I became a prep-school master. It was very jolly and I enjoyed it very much. I taught at two private schools for a period of nearly two years and during this I started an Oxford novel which was of no interest. After I had been expelled from the second school for drunkenness I returned penniless to my father. I went to see my friend Anthony Powell, who was working with Duckworth, the publishers, at the time, and said, “I'm starving.” (This wasn't true: my father fed me.) The director of the firm agreed to pay me fifty pounds for a brief life of Rossetti. I was delighted, as fifty pounds was quite a lot then. I dashed off and dashed it off. The result was hurried and bad. I haven't let them reprint it again. Then I wrote Decline and Fall. It was in a sense based on my experiences as a schoolmaster, yet I had a much nicer time than the hero.

INTERVIEWER

Did Vile Bodies follow on immediately?

WAUGH

I went through a form of marriage and traveled about Europe for some months with this consort. I wrote accounts of these travels which were bundled together into books and paid for the journeys, but left nothing over. I was in the middle of Vile Bodies when she left me. It was a bad book, I think, not so carefully constructed as the first. Separate scenes tended to go on for too long—the conversation in the train between those two women, the film shows of the dotty father.

INTERVIEWER

I think most of your readers would group these two novels closely together. I don't think that most of us would recognize that the second was the more weakly constructed.

WAUGH (briskly)

It was. It was secondhand, too. I cribbed much of the scene at the customs from Firbank. I popularized a fashionable language, like the beatnik writers today, and the book caught on.

INTERVIEWER

Have you found that the inspiration or starting point of each of your novels has been different? Do you sometimes start with a character, sometimes with an event or circumstance? Did you, for example, think of the ramifications of an aristocratic divorce as the center of A Handful of Dust, or was it the character of Tony and his ultimate fate which you started from?

WAUGH

I wrote a story called The Man Who Liked Dickens, which is identical to the final part of the book. About two years after I had written it, I became interested in the circumstances which might have produced this character; in his delirium there were hints of what he might have been like in his former life, so I followed them up.

INTERVIEWER

Did you return again and again to the story in the intervening two years?

WAUGH

I wasn't haunted by it, if that's what you mean. Just curious. You can find the original story in a collection got together by Alfred Hitchcock.

INTERVIEWER

Did you write these early novels with ease or—

WAUGH (cutting in)

Six weeks’ work.

INTERVIEWER

Including revisions?

WAUGH

Yes.

INTERVIEWER

Do you write with the same speed and ease today?

WAUGH

I've got slower as I grow older. Men at Arms took a year. One's memory gets so much worse. I used to be able to hold the whole of a book in my head. Now if I take a walk whilst I am writing, I have to hurry back and make a correction, before I forget it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you mean you worked a bit every day over a year, or that you worked in concentrated periods?

WAUGH

Concentrated periods. Two thousand words is a good day's work.

INTERVIEWER

E. M. Forster has spoken of “flat characters” and “round characters”; if you recognize this distinction, would you agree that you created no “round” characters until A Handful of Dust?

WAUGH

All fictional characters are flat. A writer can give an illusion of depth by giving an apparently stereoscopic view of a character—seeing him from two vantage points; all a writer can do is give more or less information about a character, not information of a different order.

INTERVIEWER

Then do you make no radical distinction between characters as differently conceived as Mr. Prendergast and Sebastian Flyte?

WAUGH

Yes, I do. There are the protagonists and there are characters who are furniture. One gives only one aspect of the furniture. Sebastian Flyte was a protagonist.

INTERVIEWER

Would you say, then, that Charles Ryder was the character about whom you gave the most information?

WAUGH

No, Guy Crouchback. [A little restlessly] But look, I think that your questions are dealing too much with the creation of character and not enough with the technique of writing. I regard writing not as investigation of character, but as an exercise in the use of language, and with this I am obsessed. I have no technical psychological interest. It is drama, speech, and events that interest me.

INTERVIEWER

Does this mean that you continually refine and experiment?

WAUGH

Experiment? God forbid! Look at the results of experiment in the case of a writer like Joyce. He started off writing very well, then you can watch him going mad with vanity. He ends up a lunatic.

INTERVIEWER

I gather from what you said earlier that you don't find the act of writing difficult.

WAUGH

I don't find it easy. You see, there are always words going round in my head: Some people think in pictures, some in ideas. I think entirely in words. By the time I come to stick my pen in my inkpot these words have reached a stage of order which is fairly presentable.

INTERVIEWER

Perhaps that explains why Gilbert Pinfold was haunted by voices—by disembodied words.

WAUGH

Yes, that's true—the word made manifest.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say something about the direct influences on your style? Were any of the nineteenth-century writers an influence on you? Samuel Butler, for example?

WAUGH

They were the basis of my education, and as such of course I was affected by reading them. P. G. Wodehouse affected my style directly. Then there was a little book by E. M. Forster called Pharos and Pharillon—sketches of the history of Alexandria. I think that Hemingway made real discoveries about the use of language in his first novel, The Sun Also Rises. I admired the way he made drunk people talk.

INTERVIEWER

What about Ronald Firbank?

WAUGH

I enjoyed him very much when I was young. I can't read him now.

INTERVIEWER

Why?

WAUGH

I think there would be something wrong with an elderly man who could enjoy Firbank.

INTERVIEWER

Whom do you read for pleasure?

WAUGH

Anthony Powell. Ronald Knox, both for pleasure and moral edification. Erle Stanley Gardner.

INTERVIEWER

And Raymond Chandler!

WAUGH

No. I'm bored by all those slugs of whiskey. I don't care for all the violence either.

INTERVIEWER

But isn't there a lot of violence in Gardner?

WAUGH

Not of the extraneous lubricious sort you find in other American crime writers.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think of other American writers, of Scott Fitzgerald or William Faulkner, for example?

WAUGH

I enjoyed the first part of Tender Is the Night. I find Faulkner intolerably bad.

INTERVIEWER

It is evident that you reverence the authority of established institutions—the Catholic Church and the army. Would you agree that on one level both Brideshead Revisited and the army trilogy were celebrations of this reverence?

WAUGH

No, certainly not. I reverence the Catholic Church because it is true, not because it is established or an institution. Men at Arms was a kind of uncelebration, a history of Guy Crouchback's disillusion with the army. Guy has old-fashioned ideas of honor and illusions of chivalry; we see these being used up and destroyed by his encounters with the realities of army life.

INTERVIEWER

Would you say that there was any direct moral to the army trilogy?

WAUGH

Yes, I imply that there is a moral purpose, a chance of salvation, in every human life. Do you know the old Protestant hymn which goes: “Once to every man and nation / Comes the moment to decide”? Guy is offered this chance by making himself responsible for the upbringing of Trimmer's child, to see that he is not brought up by his dissolute mother. He is essentially an unselfish character.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say something about the conception of the trilogy? Did you carry out a plan which you had made at the start?

WAUGH

It changed a lot in the writing. Originally I had intended the second volume, Officers and Gentlemen, to be two volumes. Then I decided to lump them together and finish it off. There's a very bad transitional passage on board the troop ship. The third volume really arose from the fact that Ludovic needed explaining. As it turned out, each volume had a common form because there was an irrelevant ludricrous figure in each to make the running.

INTERVIEWER

Even if, as you say, the whole conception of the trilogy was not clearly worked out before you started to write, were there not some things which you saw from the beginning?

WAUGH

Yes, both the sword in the Italian church and the sword of Stalingrad were, as you put it, there from the beginning.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say something about the germination of Brideshead Revisited?

WAUGH

It is very much a child of its time. Had it not been written when it was, at a very bad time in the war when there was nothing to eat, it would have been a different book. The fact that it is rich in evocative description—in gluttonous writing—is a direct result of the privations and austerity of the times.

INTERVIEWER

Have you found any professional criticism of your work illuminating or helpful? Edmund Wilson, for example?

WAUGH

Is he an American?

INTERVIEWER

Yes.

WAUGH

I don't think what they have to say is of much interest, do you? I think the general state of reviewing in England is contemptible—both slovenly and ostentatious. I used to have a rule when I reviewed books as a young man never to give an unfavorable notice to a book I hadn't read. I find even this simple rule is flagrantly broken now. Naturally I abhor the Cambridge movement of criticism, with its horror of elegance and its members mutually encouraging uncouth writing. Otherwise, I am pleased if my friends like my books.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think it just to describe you as a reactionary?

WAUGH

An artist must be a reactionary. He has to stand out against the tenor of the age and not go flopping along; he must offer some little opposition. Even the great Victorian artists were all anti-Victorian, despite the pressures to conform.

INTERVIEWER

But what about Dickens? Although he preached social reform he also sought a public image.

WAUGH

Oh, that's quite different. He liked adulation and he liked showing off. But he was still deeply antagonistic to Victorianism.

INTERVIEWER

Is there any particular historical period, other than this one, in which you would like to have lived?

WAUGH

The seventeenth century. I think it was the time of the greatest drama and romance. I think I might have been happy in the thirteenth century, too.

INTERVIEWER

Despite the great variety of the characters you have created in your novels, it is very noticeable that you have never given a sympathetic or even a full-scale portrait of a working-class character. Is there any reason for this?

WAUGH

I don't know them, and I'm not interested in them. No writer before the middle of the nineteenth century wrote about the working classes other than as grotesques or as pastoral decorations. Then when they were given the vote certain writers started to suck up to them.

INTERVIEWER

What about Pistol . . . or much later, Moll Flanders and—

WAUGH

Ah, the criminal classes. That's rather different. They have always had a certain fascination.

INTERVIEWER

May I ask you what you are writing at the moment?

WAUGH

An autobiography.

INTERVIEWER

Will it be conventional in form?

WAUGH

Extremely.

INTERVIEWER

Are there any books which you would like to have written and have found impossible?

WAUGH

I have done all I could. I have done my best.