Issue 26, Summer-Fall 1961

Drawings by Olga Carlisle, 1961.

Drawings by Olga Carlisle, 1961.

I telephoned Ilya Ehrenburg on my second day in Moscow, hoping to call on him, and perhaps to obtain an interview. I was adding one more request to the many he receives each day. “Ilya Grigoryevich has to be ‘avaricious’ with his time,” his secretary said when I called. “He is so occupied … but I shall convey your request to him.” Later, just as I returned to the Metropole, chilled but dazzled from a first walk along the windswept quays of the frozen Moskva River, the secretary called back to say that Ehrenburg had agreed to see me briefly. A date was set for the following week. I had good luck: Ehrenburg was in Moscow for a session of the Supreme Soviet, although he was soon due in Stockholm.

Ehrenburg lives and has his office on Gorky Street, four or five blocks from the Red Square, right in the center of town. Gorky Street, once well known as the Tverskaya, is Moscow’s major thoroughfare. It is a wide, straight, commercial street where many of the city’s principal stores stay open late into the evening. Ehrenburg’s apartment is high up in a large modern building. Several other writers and artists live at the same address. The first floor of the building is occupied by a bookstore. On one side the store opens onto a tiny square where pigeons, seemingly undisturbed by the cold weather, surround a black bronze statue of Yuri Dolgoruki. They perch irreverently all over the modern oversized representation of the mythical founder of Moscow. In the middle of the small square he is riding a huge horse, his helmeted head bent. Across the square there is a café with a pink neon sign over the entrance—a good place to meet someone for lunch without getting involved in the slow service of the big Moscow hotels.

When I went to see Ehrenburg for the first time, there was a crowd of people both inside and around the bookstore, although it was quite late in the day. A book on Impressionism had gone on sale that week. The thick volume, with a Renoir lady holding a fan on the cover, was displayed in the store window.

Bookstores are numerous in Moscow but usually very informally run and overcrowded. The books are piled everywhere in seeming disorder and avid shoppers press against counters laden with volumes. I had seen classics sold from makeshift tables on the snowy sidewalks. Crowds of modestly dressed Muscovites would line up in the sub-zero weather to purchase newly published volumes still smelling of printer’s ink.

But the bookstore on Gorky Street was more elaborate. Large and well-lighted, it had displays of books against a background of brightly painted pegboard. Inside, the various counters were clearly marked—Education, Sciences, Art—and the store was provided with an adequate number of salespeople. A vast assortment of art postcards filled an entire corner of the store. Most of them were genre paintings out of Russian museums. There were many all-time favorites, familiar even to me despite my alien education: Shishkin’s Morning in a Pine Forest, and Princess Tarakanova perishing in her prison. (She was an unfortunate rival of Empress Elizabeth II, drowned in the Peter and Paul fortress by a spring flood of the Neva. She is shown in her dungeon cringing on her bed in terror as the waters rise around her.) But I also noticed several reproductions of Impressionist work. The Impressionists, no longer considered “decadent” by the authorities, are becoming increasingly popular in the Soviet Union. The magnificent French canvases from the Moscow and Leningrad museums are now proudly displayed. Groups of viewers gather in front of the brilliant Monets and Gauguins and stand there for a long time, looking sometimes in bewilderment but more often in rapture.

When I left the store, I realized that it was later than I had thought. It was already the time set for the appointment. The sun was setting on Moscow.

Number 8 Gorky Street is a compound of buildings rather than one house. The layout is typical of Moscow, with several doorways off an inner courtyard. The courtyard was unlit and deserted, with only a few small paths dug through the snow, leading to several unmarked doors. A wall topped by an old rusted grillwork enclosed one side of the courtyard. I had a glimpse of a panorama—invisible from Gorky Street, like so many views of Moscow which one finds by accident—at the end of an old alley, between high fences. There were snowy roofs, tall reddish brick walls and suddenly an old log house, a vestige of another age. All this in irregular clusters broken by white spaces, houses set at strange angles, a feeling of casualness special to Moscow.

As is customary in this city, there was no listing of tenants or apartments to be seen anywhere. If one happens to know the number of the apartment for which one is looking, chances of finding it are fair. Otherwise one has to turn to the women wrapped in shawls who doze, sitting in the darkness, near the elevator. These somber old women seem deliberately to forget the names of the tenants. They are, or pretend to be, deaf to one’s questions. They refuse either to be wakened from their slumber or interrupted in their knitting. Perhaps their withdrawal is a vestige of earlier, darker days when people wanted to preserve their anonymity as much as possible. Or was it my slight foreign accent that put them on their guard?

If one does not know the stairway number of a particular apartment the best thing to do is to go out and telephone. Otherwise the search may turn into a Kafkaesque dream—dark stairways, cold unkempt landings, wrong doors, broken bells, crawling ancient elevators which these melancholy women in their many-layered grey shawls unwillingly operate with a special key.

I searched for the right entrance, distressed at the thought of being late at Ehrenburg’s. He had the reputation of being one of the busiest of all the Muscovite writers. I had not allowed enough time for the usual search.

Taking a desperate guess, I selected at random one stairway entrance. To my relief, it turned out to be the right one, and soon a maid was letting me into Ehrenburg’s warm apartment. An irascible small dog inspected me and retired, after barking once or twice.

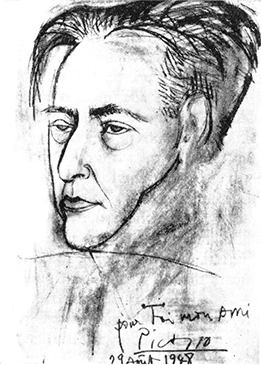

I found myself in an apartment whose decor was totally unlike the typical Moscow dwelling. It was simple, airy, and reminded me of the home of a well-to-do artistic Parisian intellectual. It was unencumbered, the furniture comfortable and inconspicuous. The drawings and paintings were mostly French. They bore friendly inscriptions to Ehrenburg from the artists. There were many black-and-whites by Picasso which gave the place an overall luminosity. Here and there a Chagall, a Léger, added a note of vibrant color, matched by the brightly patterned scatter rugs and the cushions on the sofa which were covered with handwoven folk materials—purple, deep blue, yellow. The pictures covered the walls of the living room and continued on into a hall and an adjoining room seen through a half-open door.

Mme. Ehrenburg, Lyubov Mikhaïlovna, greeted me. She is statuesque, dark-haired, and still beautiful, and was dressed with an understated elegance which is rare in Moscow. She is affable but reserved, and slow in her movements. She received me with friendliness. Years before, she had met my father in Berlin and remembered him as a handsome poet with black hair. Known for her painting, Mme. Ehrenburg once studied with the Russian “constructivist” Rodchenko. The two small canvases which she later showed at my insistence were painted not too long ago in an Expressionist manner and were quite charming. Sensing my interest, she led me around the place most readily. She took a few additional works out of a closet, several Léger lithographs from the series “Les Constructeurs.”