Issue 202, Fall 2012

Photo courtesy of Farrar, Straus & Giroux

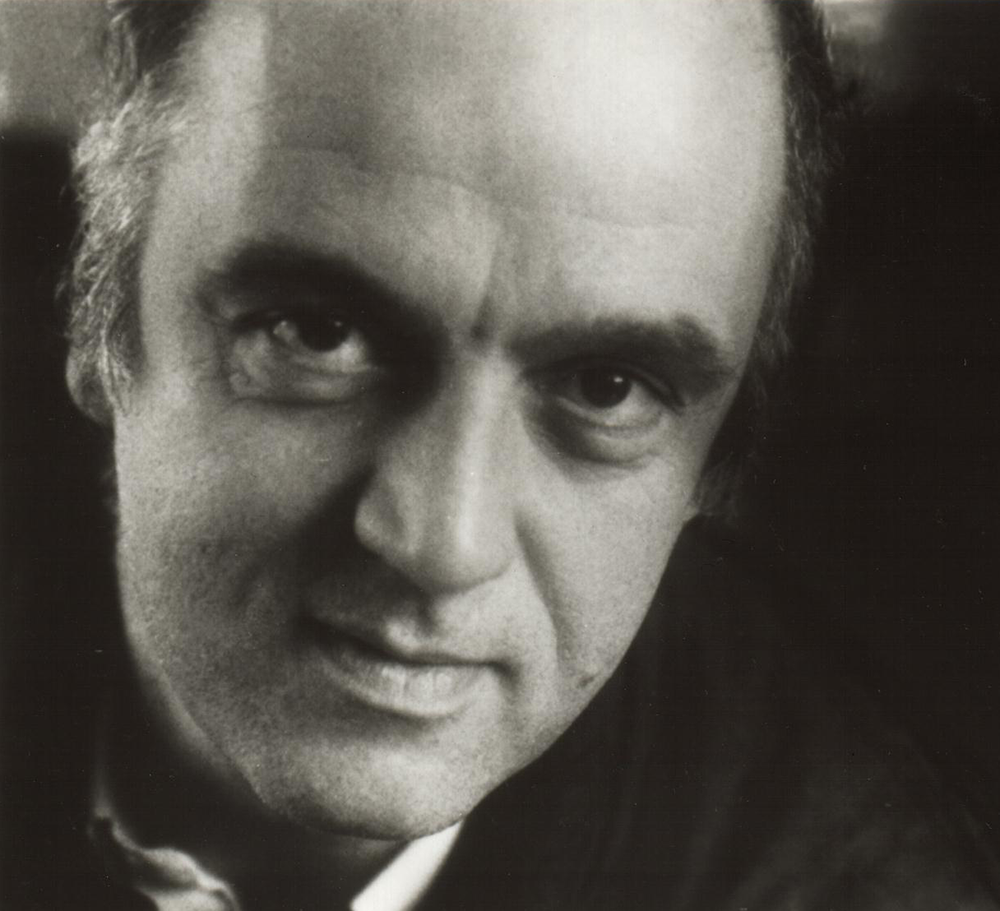

James Fenton has been a war reporter, an opera librettist, a prawn farmer, a theater critic, and Oxford Professor of Poetry. He has written books on Indochina, art history, and gardening, among other things. These disparate subjects go into his poetry, which is small in bulk but translates a remarkable range of experience.

Fenton was born in Lincoln, in northern England, in 1949. He attended the Chorister School, Durham, where he sang in the choir. He went on to read psychology, philosophy, and physiology at Magdalen College, Oxford. In 1968, he won the university’s Newdigate Prize with a sequence of sonnets and haikus on the opening of Japan. The theme was set by the prize committee, but the history of Western imperialism in Asia became one of Fenton’s abiding interests (as did questions of poetic form). Five years later, having joined the Trotskyite International Socialists, Fenton used the prize money from another poetry award to go to Cambodia. He found work as a journalist, moved to Vietnam, and reported the fall of Saigon with evident satisfaction, famously riding the first North Vietnamese tank into the compound of the presidential palace.

Fenton’s first two collections of mature work, The Memory of War (1982) and Children in Exile (1983), include many poems that look back on his time in Southeast Asia. Written at a remove of several years, they are more sorrowful than angry, dealing primarily with the aftermath of war and Fenton’s own second thoughts about it. The grim subject matter is conveyed in verses of formal elegance, even virtuosity. But war wasn’t Fenton’s only interest. The collections also include love poems, nonsense verse, and ballads. Reviewing these volumes in The New York Review of Books, Seamus Heaney contrasted them with the brooding, apocalyptic poetry of Ted Hughes and wrote that Fenton’s verse “reestablished the borders of a civil kingdom of letters where history and literature and the intimate affections would be allowed their say.”

Fenton served as Oxford Professor of Poetry from 1994 to 1999. His lectures on modern English, Irish, and American poets were published as The Strength of Poetry (2001). During the same period, he began writing art criticism for The New York Review of Books, much of which is collected in Leonardo’s Nephew (1998). He has also written a short book on gardening, A Garden from a Hundred Packets of Seed (2001); a primer on English poetry, with especial attention to metrics, An Introduction to English Poetry (2002); and a history of the Royal Academy, School of Genius (2006).

Our conversation occurred in two parts. The first was a live interview at the New York Public Library this past spring. Fenton has the reputation of an accomplished reader, and during our conversation I asked him to recite aloud a pair of his own poems. Fenton’s voice is deep, his enunciation quick and deliberate, and his physical presence is imposing when he wants it to be. This gravitas is helped by the fact of his head, which has been evoked many times: Ian Parker, in a New Yorker profile, described it as “a boulder of a bald head.” Fenton’s friend Redmond O’Hanlon called it “an owl’s egg.” “Ah, that head!” Christopher Hitchens once rhapsodized. “It certainly did have the most domed and sapient appearance.” The readings also provided an object lesson, for Fenton is an outspoken believer in poetry as performance. It is, he once told me, an art of “the lips and the limbs.”

The second part of the interview was conducted in Fenton’s new home in Harlem. This is one of the more romantic residences in New York City, an enormous nineteenth-century town house originally built for John Dwight, founder of Arm & Hammer. After World War II, a group of African American Jews converted the structure into a synagogue, etching Stars of David into the windows and filling the second-floor dining room with pews and a bimah. Today, it is both a ruin and a construction site. Fenton and his partner, Darryl Pinckney, live on a single floor—or, rather, camp out, storing their clothes in portable closets and showering at their respective gyms. Their plan is to restore as much of the original ornamentation as possible. Fenton’s previous house, a large farmstead outside Oxford, was famous for its sumptuous gardens. In Harlem, the flora is more discrete. Before our talk, he showed me where he had been scraping a wall that morning. Behind several layers of plaster, there was a vivid patch of blood-red, with hand-painted flowers in yellow and white.

INTERVIEWER

Recently you’ve been working on a playscript for the Royal Shakespeare Company. Can you say what it is?

FENTON

It’s my version of an old Chinese play, the first Chinese play to be translated in the West, called The Orphan of Zhao. There are a few eighteenth-century versions, including one by Voltaire. But it hasn’t been done for some time since. The idea of the RSC is to put it on as an example of the kind of thing that was going on in the theater in Shakespeare’s day, but well away from the Shakespeare tradition. The earliest version is what they call a set of arias, a series of texts sung by the actors. The music doesn’t survive, nor does the actual dialogue of the play. All we have are these monologues in which a character steps forth and explains what his predicament is.

INTERVIEWER

What’s the play about?

FENTON

It’s about destruction. The setting is the emperor’s court. There’s a high official who wants to eliminate one of the ministers and to destroy his whole clan as well. Not just the family, also the servants. A doctor is asked to save this minister’s newborn son. To do so, the doctor must sacrifice his own son, which indeed he does. The newborn grows up in the court of the official who has ordered his execution. When I was telling this story to someone the other day they said, to my surprise and delight, “It’s Argentina.” And it really is a story about someone adopted by the very people who killed his parents.

INTERVIEWER

The RSC is advertising it as the Chinese Hamlet.

FENTON

Well, it is a revenge play. The orphan character grows up not knowing who he is, not knowing that his stepfather destroyed his whole clan. But once he does know, he moves very quickly. He’s not like Hamlet in that respect.

INTERVIEWER

What drew you to the play?

FENTON

Most of my projects with the RSC have ended in tears. I spent quite a lot of my life doing a version of Don Quixote for the RSC and nothing happened with it. I was drawn to this one by the man who’s directing Zhao—Greg Doran, now artistic director of the RSC, whose previous productions I’ve admired—and by the fact that it was already scheduled. We did a public reading of the play over spring break in Ann Arbor, where the RSC has a residency. I presented what I had done, which was half the play, and it seemed—strangely enough—to work.

INTERVIEWER

How have you handled the language of the play?

FENTON

The language is very formal, not conversational, and I haven’t tried to loosen it up. When a character comes onstage, he says who he is. If he’s a main character, he says what’s on his mind. The dialogue follows from that. This way of presenting the characters is, of course, completely unlike realist drama. But it is dramatic. And the way it’s played is not formal—the actors play it for the emotions. In Ann Arbor, we had people in tears. Me, first of all.

INTERVIEWER

I wonder if you might read something aloud, one of the songs, perhaps “The Song of the General”? Would you set it up before you start?

FENTON

I should say that the songs are my own invention, they’re not in the Chinese. The first thing I did was to write a song that would kick off the story, then one to begin act 2, and then one to finish. “The Song of the General” is sung by a man named Wei Jiang, one of the good guys. He’s gone into a kind of self-imposed exile, because the court is so corrupt. He spends eighteen years on the border, and now a message comes to him that the emperor is dying. The general has a month to get from the edge of the kingdom back to the court, so he’s got to decide what to do. [Recites “The Song of the General,” see page 63.]

INTERVIEWER

It makes me think of all those laments by border guards one finds in classical Chinese poetry—Pound’s version of “Song of the Bowmen of Shu,” for example. When English readers think of classical Chinese poetry, most of us do think of the idiom Pound created in the translations in Cathay. It’s a spare, elegiac language—imagism, in a word. But your song doesn’t sound Poundian to me. Who were you hearing when you wrote it?

FENTON

I was hearing a three-beat line. I was thinking, There will be a composer, and he’s got to be able to do something with this. The line goes, da da dum dum dum, da da dum dum dum. If the composer can’t do that, there’s something wrong with him. All the rest was instinctive. At Ann Arbor there was a sinologist who came to the rehearsed reading, and I asked him afterward whether he thought what I had done was in a plausible idiom. And he said, It’s very like a lot of things in The Book of Songs. At which point I thought, I must reread The Book of Songs. So I have been, in Arthur Waley’s translation, and was thrilled to find that I must have remembered something of it from a long time ago.

I’m not very attracted to the scholarly, moon-over-the-mountains poetry. I’m more interested in the rich vein of “this is the military life” or “a catastrophe has passed across this land”—that kind of thing. There’s an incredibly old song mentioned in the introduction to The Book of Songs about somebody named Duke Mu, who has died and been buried. Each stanza begins, “Kio sings the oriole,” and then the oriole lights upon a certain kind of tree, which varies in each stanza. There’s also a different person in each stanza, and each one contains the line “Tu Fu”—or whatever his particular name happens to be—“shuddered when he entered the corridor of the duke’s tomb.” It goes on like this for several stanzas, each with a different name and the oriole landing in a different tree. The reason I find this poem so exciting is that it refers to an ancient custom from the time before the Xi’an tombs—so, right at the beginning of Chinese history—of people being strangled and put in the tomb with the dead ruler.

But I also suddenly remembered a song from my childhood that used to be sung at children’s parties. It went, “Wallflowers, wallflowers, growing up on high / We are only maidens and we shall surely die, / Excepting one, and her name is Anne.” Or, “And his name is John.” Then you go, “And O for shame, and fie for shame, / And turn your face to the wall again.” I can still hear my mother singing this song. There was a dance that went with it. Everyone went around in a circle and then somebody got caught and that was the one who survived. All the others died. Very strange thing to do at a children’s party. And clearly a very old piece of folklore. Then it occurred to me that Duke Mu’s song would have had music and a dance that went with it, too. We don’t have the dance, of course. Nor do we have the music. Chinese musical notation doesn’t go back that far. These are the earliest forms of literature, probably, in the world.