Issue 205, Summer 2013

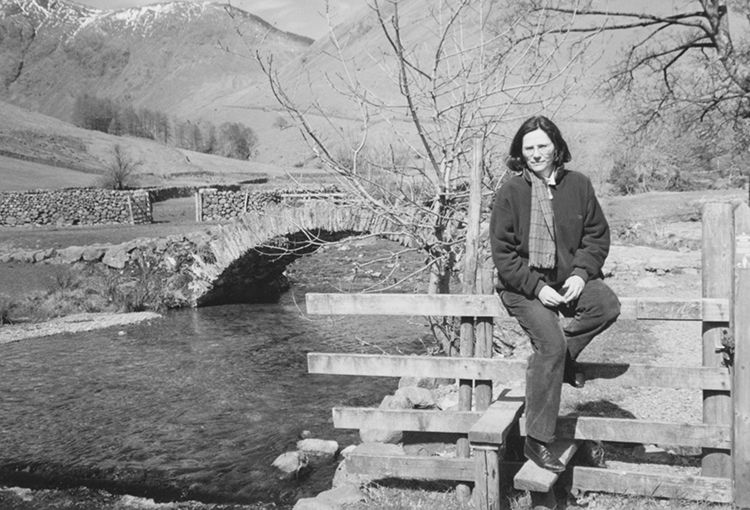

In the Lake District, 1994.

In the Lake District, 1994.

The first time a publisher approached Hermione Lee with the idea of writing a biography of Virginia Woolf, she said no. “I thought it was ridiculous,” Lee recalls. Then a second publisher suggested the same thing. “At that point, I thought, Clearly, people feel it’s the right time to have a new biography of Virginia Woolf, and clearly, more than one person thinks I should be the one to do it.” Lee wouldn’t, though, do it in a traditional, linear way. Instead of a fact—a name, a place, a birthday—she opened Virginia Woolf (1996) with a question that Woolf herself asked: “My God, how does one write a Biography?”

Although Lee did keep chronology in view, she approached her subject by theme, topic, and scene. The result was an original and sensitive account of a complex life. The same is true of each of Lee’s biographies: Willa Cather (1989) is a hybrid of biography and literary essay; Edith Wharton (2007) considers Wharton not only as an American author but as a European one, drawing on a wealth of social, psychological, material, and historical detail. In all three books, Lee weaves masterly discussions of her subjects’ work into the stories of their lives.

Apart from her biographies, Lee has written book-length monographs on Woolf, Elizabeth Bowen, and Philip Roth. She has also written short books about life-writing, as well as countless reviews, essays, and introductions. From 1982 to 1986, she hosted a television show about books, Book Four, on British television’s Channel 4, and she is a frequent contributor to BBC Radio. After Lee graduated from Oxford, she taught at the College of William & Mary, the University of Liverpool, and, for twenty years, the University of York. In 1998, she was appointed to the Goldsmiths’ Chair of English Literature and Fellow of New College at the University of Oxford. In 2008, she was elected president of Wolfson College at Oxford.

Our sessions took place early last spring. It was a busy time for Lee, who had just returned from Brussels, where she had given a talk about Isaiah Berlin’s 1945 encounter with Anna Akhmatova. The following week, Lee traveled to New York and then to Los Angeles to deliver lectures on Edith Wharton. Then she was headed to Yorkshire, where she and her husband, the literary scholar and editor John Barnard, spend part of the year, to finish her life of Penelope Fitzgerald.

We met in Oxford, at a house hidden from view by a high hedge, on a quiet street at the edge of town. The house had an immaculate, rather grand foyer and a kitchen that seemed designed with caterers in mind. Lee was quick to point out that the place is not hers: it comes with her job. “I don’t garden here because”—her voice dropped to an anxious whisper—“I might worry the gardeners.” Her office upstairs, though, revealed her own distinctive taste for elegance and order. Framed photographs of Woolf hung on the wall; a raft of paper clips stood on her nineteenth-century partners desk. The only thing that appeared out of place was an odd pile of boxes and papers covered by a faded, crocheted blanket. It was the Fitzgerald family archive. Lee’s biography of Penelope Fitzgerald will be published later this year.

—Louisa Thomas

INTERVIEWER

Virginia Woolf wrote a lot about how difficult it is to know anyone, even— or especially—oneself. When she was working on a memoir, she wrote, “I see myself as a fish in a stream; deflected; held in place; but cannot describe the stream.” How did you find the nerve to write her biography?

LEE

What makes her such an alarming prospect is also what makes her a very inviting subject for biography. She herself is deeply interested in the genre. In that memoir, “Sketch of the Past,” and in her fiction and essays and diaries, she keeps returning to the question, How do you tell the life story of a person? I think that’s her prime interest. And because of her own interest in the complexity of the adventure of writing a life, and because of all the material in her gigantic archive, you are privy to how she thinks of herself as well as to how other people think of her and how she’s presenting herself. She’s not one of those difficult subjects for a biography, where you have hardly any information—like Shakespeare or Jesus. And she’s not the kind of resistant subject, such as Willa Cather, who is like a wall of steel, preventing anyone who tries to come near her. The challenge with Woolf is that she has been so mythologized, so written about, so appropriated—and is herself so complex and multifaceted.

INTERVIEWER

Is fear a useful emotion for a biographer?

LEE

It can be, when it’s not disabling. You would have to be an idiot to take on board writing the life of Virginia Woolf or Edith Wharton without any apprehension. The fear has to be channeled somehow into the energy of the work. While you’re doing it, I think you have to feel that she is yours and you alone understand her. But in order to arrive at that feeling you have to deal with, and master, your apprehension. I had a conversation with the biographer Richard Holmes, ages ago, when I said I always felt rather daunted by the task. I always had voices at the back of my head saying, She doesn’t know what she’s doing. She can’t do this. He said, “You know what I do? I get to my desk every morning and I hear these little voices saying, ‘He doesn’t know what he’s doing!’ and I raise my arm and I just sweep, I sweep them off the desk.” I had a vision of these little jabbering gremlins, like the germs in those advertisements for lavatory cleaners, being swept off and away. No more fear!

INTERVIEWER

What’s gained in learning about the life of an author?

LEE

You learn how that person works in all senses of the word works. You learn something historical. You learn how a book evolves and how it emerges from the muddle and the mess and the complexity and the contradictions of a person’s life. You learn about all the things that human beings are interested in.

But when you read the biography of a writer you love, you also do lose something, there’s no doubt. When I first read Katherine Mansfield, as a child, I had no idea she was a New Zealander. It just seemed to be a magic country—I knew nothing about it. And that was part of the spell. When I was a child, about eight years old, I went to stay with a family and I picked up a copy of The Waves that happened to be at my bedside. It was the first book by Virginia Woolf I ever looked at. I read the pages at the beginning, where the children are speaking in single phrases. I just thought, This is my language, even though I had only read two pages and didn’t know what was going on. So I think that primal, childlike reading, where you know nothing, is very important. And reading biography interferes with that.

INTERVIEWER

You wrote about that experience. You called it a “secret language.” Secret is a word you use often when you write about women.

LEE

In the 1980s, I edited two anthologies of stories by women called The Secret Self. The title was taken from a line of Katherine Mansfield’s—“One tries to go deep—to speak to the secret self we all have.”

INTERVIEWER

Cather uses it when she’s writing about Katherine Mansfield.

LEE

She does. I’m very interested in that idea of secrets. Edith Wharton says, in a story, that a woman’s life is like a great house full of rooms, and you never get to the secret room. I’m fascinated by these no-go areas, these secret places of reserve. At the same time, I’m extremely inquisitive and curious. Perhaps that’s temperamentally why I’ve been attracted to biography. I want to penetrate those secret places, find out everything, and be completely ruthless. It’s paradoxical—I wouldn’t want it done to me, yet I’m very keen to do it to other people. And the thing that attracts me to these people is their secret self.

INTERVIEWER

To what extent are you conscious of being a woman writer, or writing about women subjects?

LEE

I haven’t written only about women. Thirty years ago, in 1982, I wrote a short book on Philip Roth, whom I also interviewed for The Paris Review. I’ve written about Kipling and Trollope, Ford Madox Ford, William Trevor, Alain-Fournier, John McGahern. Still, it’s true that my books have been mainly about women. There is a form of feminism in that, though I don’t set out to write feminist biography. My subjects do have things in common, but those things aren’t essentially to do with their being women. Looking back, I see I’m attracted by subjects who are individualistic, who don’t like joining movements, who have carved out their own ways, who have remarkable minds, and whose marriages or partnerships, when they work well, work as forms of companionship. All my subjects up to now have been childless, but now I’m writing about the English novelist Penelope Fitzgerald, whose three children were very important to her. I’m not saying there is anything autobiographical about my choice of subjects. I’m saying only that these are the kinds of figures who interest me. If they have a feminist agenda, as Woolf did, it’s a very complicated one. Beyond that I can’t go. I certainly can’t say to you, I have set out to be a woman writer writing about women writers.