Issue 217, Summer 2016

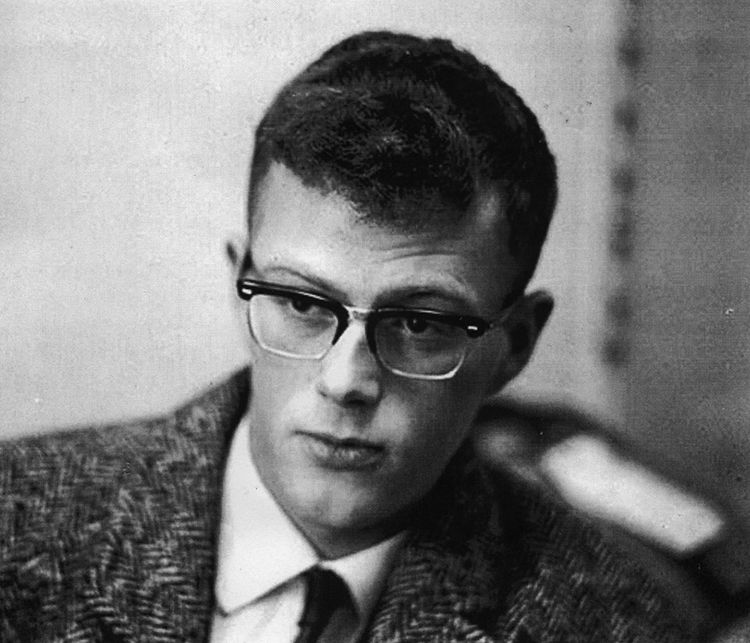

Dag Solstad in 1965.

Dag Solstad in 1965.

Since he published his first book of stories in 1965, Dag Solstad has been to Scandinavian literature what Philip Roth has been to American letters or Günter Grass to German writing: an unavoidable voice. Over the years, his stature has only grown. When he published a novel dealing with the war in Afghanistan, in 2006, it was reviewed by none other than Norway’s foreign minister. When he published a novel based on his family history, in 2013, it provoked a major critical debate on the borders between fiction and nonfiction.

Solstad started his career as a journalist for a local newspaper, before joining the Maoist Arbeidernes Kommunistparti (marxist-leninistene) (AKP) in 1970. Combining political perspectives with existentialist concerns, Solstad has written eighteen novels as well as stories, plays, essays, and nonfiction, including the official history of one of Norway’s largest industrial companies and five books about the World Cup.

In Scandinavia, Solstad’s unique style—long meandering sentences, bursting with imaginative digressions and rife with a peculiar dry humor—has served as inspiration for generations of writers. “His language,” writes Karl Ove Knausgaard in My Struggle, “sparkles with its new old-fashioned elegance, and radiates a unique luster, inimitable and full of élan.” In recent years, he has gathered a following abroad, including Peter Handke; Haruki Murakami, who has translated Solstad into Japanese; and Lydia Davis, who taught herself Norwegian by reading his four-hundred-page novel Telemark.

Our interview took place in two sessions last year and was conducted in Norwegian. The first was at his summer residence on Veierland, an idyllic island famed as a getaway for writers and artists since the painter Edvard Munch spent summers there in the 1880s. Our second conversation took place in Solstad’s home in Oslo, a large, bright, book-filled apartment with high ceilings in an elegant nineteenth-century town house. Solstad has an eye for how social change manifests itself in everyday activities; he began our second session by directing my gaze to a scene outside his window. “Look,” he said, pointing to a road worker eating his lunch inside his truck: in his sturdy, greasy overalls, the man precision-picked a beautifully decorated plate of sushi.

Once known as a highly uncooperative interviewee—he famously snubbed a journalist with one-word answers for the length of a TV interview—Solstad has, in later years, opened up, saying he has no remaining fears of what people may think of him. At seventy-four, his presence is a friendly and welcoming one. Serving tea and cookies, he frequently paused to reflect on questions and just as frequently laughed at his own answers.

—Ane Farsethås

INTERVIEWER

What made you want to write?

SOLSTAD

Oh, reading Knut Hamsun at sixteen. I doubt I would have become a writer if I hadn’t. I think that has been my goal—to write books that could do what Knut Hamsun’s books did to me. I was introduced to Hamsun by a schoolmate, a boy from a working-class family who quit before graduation. I never saw him again, but I’ve remained thankful for his recommendation.

Once I started, I read everything in one go. I went to the library several times a week to borrow more books, and I cleverly wrapped them in the paper we used for schoolbooks so it would look like I was doing my homework, studying like hell!

INTERVIEWER

What in Hamsun appealed to you?

SOLSTAD

The stories about unrequited love—Pan and Victoria. I can admit that now. Today, like any grown-up, I prefer Hunger and Mysteries, the modernist novels. But as a young man, that kind of desperate romanticism was something I could really identify with. And his wonderful prose, of course. I was actually quite good at imitating it. I wrote some editorials in the school paper that were very good—but pure Hamsun. In hindsight, it is obvious that many writers have been overly influenced by Hamsun. His work is not always well structured, his ideas not always well thought through, and yet as time went on, his style became a sort of literary ideal. He is one of those writers who sits there, pondering his sentences, his sounds and rhythms, and then actually nails it, in one lucky shot. It’s like football—a good team is always lucky. A good writer is always lucky. Very lucky.

INTERVIEWER

Have you been lucky?

SOLSTAD

Oh yes. For example, some passages I’ve written have made me doubt—Can I publish this, can I live with this being out there? And I’ve thought, I really can’t, but I’ll keep it anyhow. Generally it has worked out well. That’s luck, because I could just as easily have deleted those passages. I have deleted a lot.

INTERVIEWER

Your writing gives the opposite impression—that you don’t edit much.

SOLSTAD

It may look that way, but I have actually been very concerned with what to keep or not. I have also, for almost every single book, toyed with the idea of writing a diary on how that book came to be. I’ve always wanted to record the process, but it’s nearly impossible to be a hundred percent immersed in a book and have the distance necessary for that at the same time. But in one of my novels, Armand V. Fotnoter til en uutgravd roman, I included some reflections on how that book came about. It describes how sometimes you have this feeling that the novel already exists and that your job is to excavate until you uncover that which is, on some level, already written.

INTERVIEWER

Have you always felt that way, that you are excavating something already there?

SOLSTAD

Oh no. When I started writing, at twenty-three, I began with short stories. A novel just seemed too daunting—I didn’t know where to begin. I couldn’t start a novel of four hundred pages and then realize at page 250 that it was hopeless. I have too much common sense, so I went for something smaller. I moved to a remote village in the north of Norway to work as a teacher. I told people I would earn money to continue my university studies, but in reality I had decided I would write.

INTERVIEWER

Who were your early influences, besides Hamsun?

SOLSTAD

My first two books of stories were certainly influenced by Kafka, The Castle and The Trial. I tried reading Dostoyevsky, but I didn’t get him until I was in my late twenties. All the writers I have learned from, except Hamsun, I found after I became an adult, after I became a free human being, freed from the prison house of childhood.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve said that you do not see childhood as a literary subject.

SOLSTAD

And I have written almost nothing about childhood. There simply is nothing you can do about it. It is too determined, the positions are too fixed. I prefer placing my characters in situations where they have a reasonable chance of escape.