Issue 243, Spring 2023

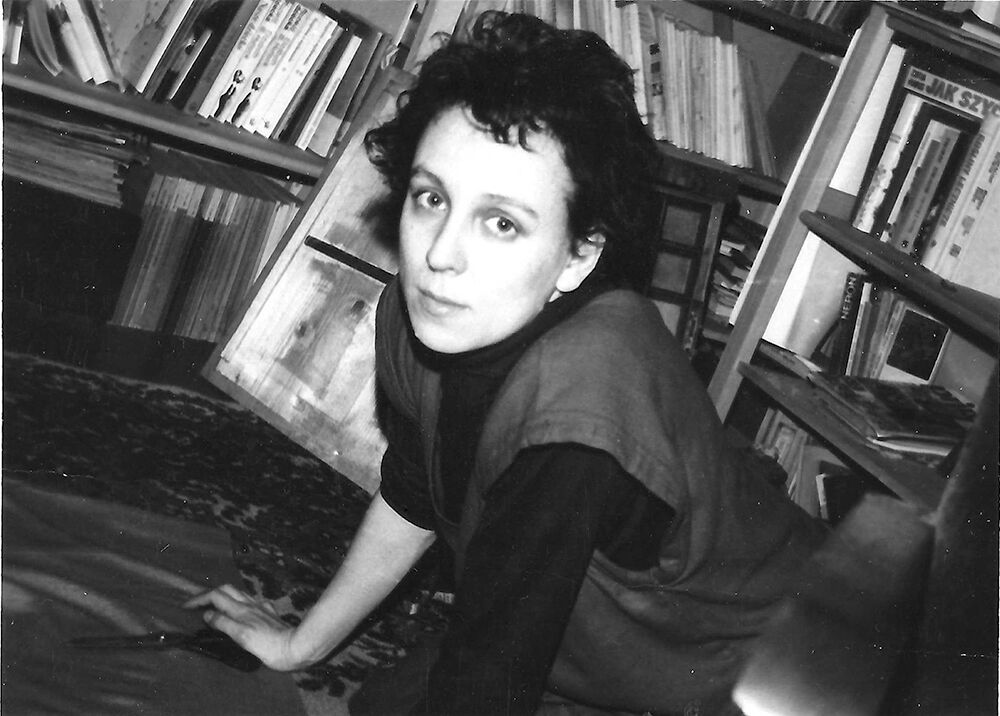

In her bookstore in Wałbrzych in the late eighties. Courtesy of Olga Tokarczuk.

Olga Tokarczuk is young for a Nobel Prize winner. She received the award four years ago, at fifty-seven, for “a narrative imagination that with encyclopedic passion represents the crossing of boundaries as a form of life.” Her painstakingly researched novels recover forgotten chapters of Eastern and Central Europe’s multilingual, multicultural history, drawing on Gnosticism, Kabbalah, Apocrypha, tarot, and pre-Christian paganism. Her insistence on tackling the long entwinement of Polish and Jewish cultures and the notion of gender as fluid—and as a social construct—has made her a controversial figure in her conservative home country of Poland. In 2019, the minister of culture, when asked for his thoughts on Tokarczuk’s work, said he’d never made it through any of her novels.

Tokarczuk was born in Sulechów, in western Poland. When she was nine, her family moved south to Silesia, a region that has, over the centuries, frequently changed national ownership, and that forms part of Europe’s sanatorium belt, which includes the Davos of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. Her father was a refugee from Ukraine who barely escaped the country’s midcentury eruption of interethnic violence; her mother came from southeastern Polish peasantry. Before committing to writing full-time, Tokarczuk worked as a psychotherapist and ran a small publishing house and a bookstore. She made her debut in 1993 with Podróż ludzi Księgi (Journey of the people of the Book), a parable-like novel set in early modern France and Spain. E. E. (1995), a narrative reckoning with Carl Jung and the psychoanalytic enterprise, was followed by Primeval and Other Times (1996, translation 2010), which became a national bestseller. House of Day, House of Night (1998, 2002), a lyrical, polyphonic ode to the real and legendary histories of Lower Silesia, won critical recognition across Europe.

The Anglophone world caught on to Tokarczuk belatedly, through the combined efforts of her translators and of her first English-language publishers, Granta Books, Northwestern University Press, and Twisted Spoon Press, as well as of her current British publisher, Fitzcarraldo Editions. Jennifer Croft’s 2017 translation of Flights (2007) won the Man Booker International Prize in 2018; Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead (2009, 2018), translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, was short-listed for the same award the following year. Her magnum opus, the nine-hundred-plus-page The Books of Jacob (2014)—which tells the story of Jacob Frank, an eighteenth-century Jewish mystic who declared himself the Messiah and established a surprisingly long-lived syncretic cult—was finally released in Croft’s English translation in 2021. Most of her numerous short stories and several of her novels, including Empuzjon (2022), a rewriting of The Magic Mountain, have yet to be translated.

To get to Krajanów, the tiny village in Lower Silesia where Tokarczuk has lived for three decades, I took a one-car train from the regional capital, Wrocław, known in German as Breslau, to Nowa Ruda, the next village over. Tokarczuk and her husband, Grzegorz, met me with their dog, Timi, and drove us home up a potholed mountain road. From the cavernous house’s kitchen windows, the trees stared back at me: Tokarczuk and her sister, Tatiana, who lives nearby, paint fresh blue eyes on their trunks every spring. In the library, opposite an iron plow hanging at a wild angle, I found a painting of Tokarczuk as a snake-haired Medusa holding a mirror. In real life, a nest of dreadlocks—some beaded, others dyed blue or green—towers over her head. Local superstition has it that this hairstyle, the kołtun (known since the late Middle Ages as plica polonica, the Polish plait), protects its wearer from maladies and curses.

Our conversations took place over four days and copious amounts of tea and coffee, as well as homemade herb-infused slivovitz. We took breaks to stew apples and watch Taiwanese horror films. One afternoon, we visited a roadside chapel dedicated to Wilgefortis, a bearded female folk saint whose legend Tokarczuk fictionalizes in House of Day, House of Night. Members of the church community had sanded off Wilgefortis’s troubling facial hair—still, a five-o’clock shadow lingers on the wooden jawline.

INTERVIEWER

Do you ever get lonely, living in such a remote place?

OLGA TOKARCZUK

Far from it. When we moved here, in 1993, I was feeling depleted after years of living in the city. We bought the house from a group of hippies who’d given up on trying to live out in the wild. It was completely dilapidated. There were only dirt roads, and it got snowed in on a regular basis. There were no neighbors around then. I was surrounded by a wilderness that has always threatened to overwhelm human habitation. To me, all this was a gift—I finished Primeval and Other Times here, and I wrote House of Day, House of Night, feeling I could hear whispers coming from the walls.

Many of the people in this area, myself included, feel that we’re living on the ruins of an alien civilization. It had always seemed to me that I heard the hum of water within the house, and no one believed me until we did renovations in our cellar. When we dug out the foundation, it turned out there was a stream running right underneath. That’s how the Germans used to construct homes on the slopes of mountains—they didn’t fight the water, they just let it flow right through the buildings. The people who have chosen to settle here since the war have tended to be eccentrics, oddballs—disparate people whom fate has brought to the region. At one point, I was neighbors with three different translators of William Blake—that obviously inspired Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead. This basin seems to attract them, as it does other mystically inclined people—lovers of Meister Eckhart and of Jakob Böhme.