Issue 245, Fall 2023

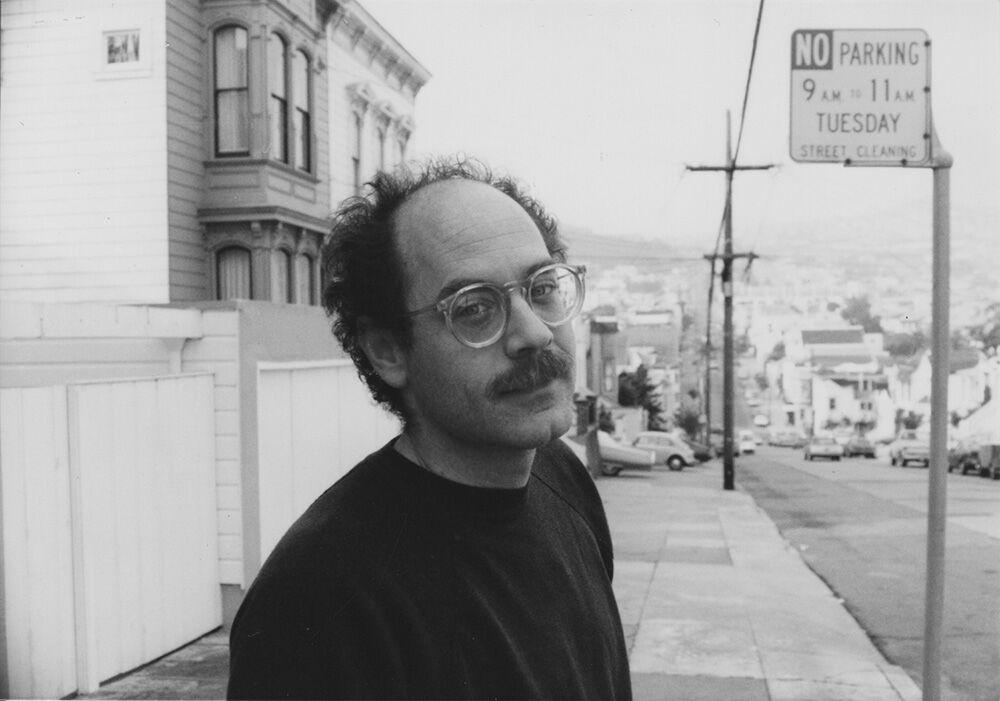

On Clipper Street in San Francisco, 1982. Courtesy of Robert Glück.

Robert Glück’s best-known work, Margery Kempe (1994), is an entirely original novel that juxtaposes apparently autobiographical episodes from the life of “Bob,” a man who has an all-consuming passion for his younger lover, L., with the travails of the titular mystic as she pursues a very hot, very psychedelic, and not particularly saintly romance with the only son of God. The book’s republication in 2020, by NYRB Classics, confirms the old chestnut that great writing will find its readers.

Glück was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1947. When he was ten or eleven, his father, a traveling salesman, moved the family to Los Angeles. In 1964, Glück began college at UCLA, and during a junior year abroad in Edinburgh, he explored his interests in medieval and Renaissance painting and discovered a talent for ceramics at the College of Art. On returning to the U.S., he transferred north to the University of California, Berkeley, where, against the backdrop of the anti–Vietnam War protests, he read Chaucer and Frank O’Hara. For much of his adult life he was involved with Enola Gay, a group of gay male activists who staged actions opposing the development of nuclear weapons, for which Glück, at one point, spent two weeks in prison. He did not participate in all their demonstrations. “When they were going to bury a crystal at the beach to stop war, for instance, I told them, ‘I’ll join the ritual when there’s human sacrifice,’ ” he said, making easy reference, as he often does, to the writings of Georges Bataille.

In the late seventies, Glück spearheaded the New Narrative movement. At a San Francisco bookstore, Small Press Traffic, he led free community workshops, attracting a social scene that soon included Steve Abbott, Kathy Acker, Mike Amnasan, Dodie Bellamy, Dennis Cooper, Sam D’Allesandro, Camille Roy, and Gail Scott. Their writings, which embraced gossip and a profusion of sensory detail, and which sought to capture the American experience of being queer, or female, or decentered in other ways, stood in contrast to the more impersonal formalism of the era’s Language poetry.

Glück has little faith in the notion of the writer as solitary genius. In 1981 he and his New Narrative cofounder, Bruce Boone, self-published La Fontaine, a series of experimental cotranslations of the French writer Jean de La Fontaine. He has invited collaboration ever since. Jack the Modernist (1985), his first novel, incorporates real conversations and anecdotes, while Margery Kempe’s startling descriptions of sexual sensation borrow from remarks he solicited from friends. His novel About Ed, to be published this fall, is a portrait of—and a kind of posthumous collaboration with—the artist Ed Aulerich-Sugai, his longtime friend and his partner between 1970 and 1978, who died of AIDS-related complications in ’94. Glück is also the author of many essays, collected in Communal Nude (2016); two books of poetry; and two story collections. The first of these, Elements (1982, originally titled Elements of a Coffee Service), shows the influence of his cohort’s readings of Roland Barthes and Walter Benjamin, and the second, Denny Smith (2003), is at times reminiscent of the work of Frederick Barthelme or Lydia Davis, a friend of Glück’s.

Glück, who has worked as a professor of creative writing and as the director of the Poetry Center at San Francisco State University, lives in Noe Valley with his husband, Francesc Xavier Permanyer Bel, an engineer. Our conversations began in spring 2022 and continued over the next year. While we spoke, I would occasionally put my phone on speaker so that I could quietly entertain my two-year-old, and sometimes, on hearing him interject, Glück—who became a father at forty-six—would make small talk. “Oh, you like tomatoes? I’m a tomato man myself.”

One evening this past March, I met Glück at the Poetry Project in New York City. Wearing his favored gold-rimmed spectacles and a simple black vest over a blue button-down, he read from I, Boombox (2023), a long poem fashioned from his misreadings of various sources—“Start a genital uprising”—to an audience of rapt twentysomethings. His powerful smile develops in several stages: glimmer to sunbeam to parting of the heavens.

INTERVIEWER

I’m sorry to be late. I ran into someone I’d bonded with during lockdown because both of us got divorced after we were cheated on by our spouses. He was right in the middle of it, and he was doing that thing where you just tell every single person you see.

ROBERT GLÜCK

Like the ancient mariner—that’s his story to tell.

INTERVIEWER

You just can’t stop.

GLÜCK

I’ve been there. Well, obviously I have. When people would ask me—and sometimes they did—to write about them, I’d reply, “First, break my heart.”

INTERVIEWER

What is it about heartbreak, do you think?

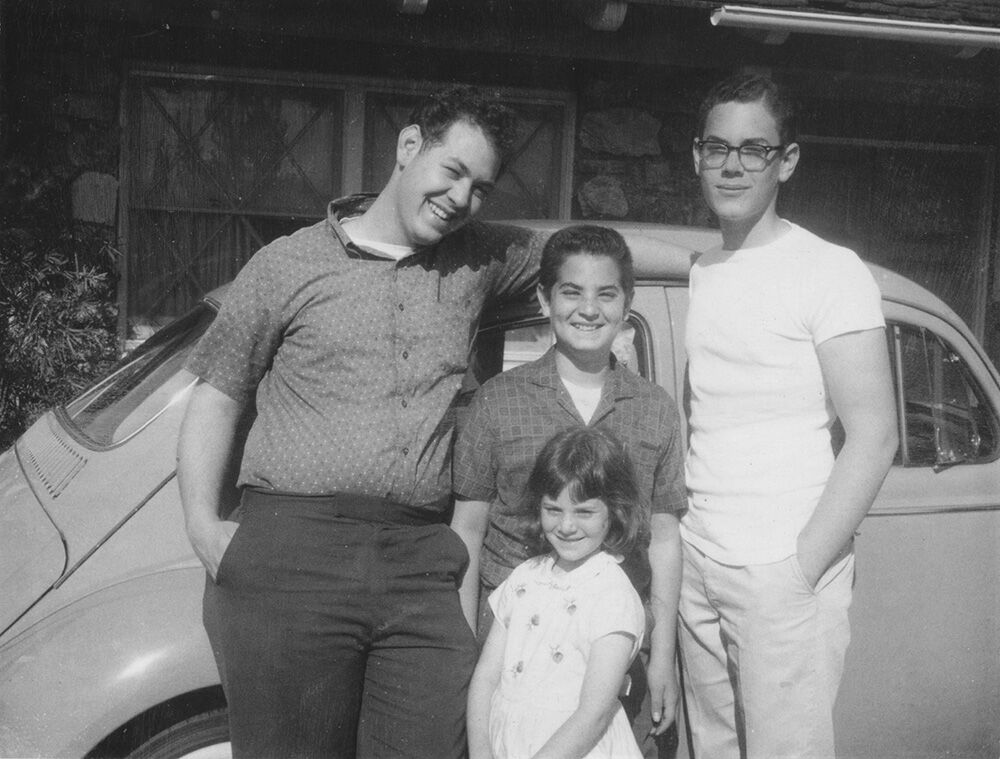

At right, with his siblings in Los Angeles, ca. 1960. Courtesy of Robert Glück.

GLÜCK

I think, in my writing, I want to display a self that disintegrates. I can prop that up with theory, but something must compel me in the first place. I suppose that’s when the world can enter. Goodbye, defenses. Somewhere, I’ve described my aesthetic as “a meticulous account of lightning striking.”

INTERVIEWER

Two ingredients often come together in your novels—a beloved person and a beloved literary corpus. How did you start writing that way?

GLÜCK

Golly. I think about the workshops I ran at Small Press Traffic in the seventies and eighties, how reading became a part of writing. We were reading our lives and living our fictions. Most of my education was simply the books that Bruce Boone handed me. We were drawn to the Frankfurt School—to Walter Benjamin, for a melancholy that reads like autobiography. Even his densest work has a strain of feeling going through it. Roland Barthes, too—we absorbed Mythologies, those tasty essays, and A Lover’s Discourse and other books, and we adapted his lofty style to our needs. In the workshops, I would bring xeroxes of work by poets and fiction writers along with Kristeva, Foucault. When Steve Abbott discovered Georges Bataille, all of us in the New Narrative group began reading him. We started with an early work, Story of the Eye, and a late one, Death and Sensuality, now called Eroticism. In Jack the Modernist, I wanted to refract a romance through Bataille’s excesses—or let’s say he gave me access to my own experience.

I came across an early manuscript of Jack just last week, and by chance I turned to the bathhouse scene. That’s the point in the book where I went furthest into sex. I even borrowed language from Bataille, although people are watching a sex act instead of the Mass or a human sacrifice. I was writing this in ’81 or ’82, ten minutes before HIV, when sex was still at the center of gay life. By the time the book came out, in ’85, death had become the center. Anyway, in this draft, at the most intense moment—I’m getting blown and fucked at the same time—I had included my salary. My thinking was that most people will tell you anything about their sex life, but nobody will tell you their salary. If I’m exposing myself, why don’t I really do it? I showed it to my friends, and every single one of them said, “You have to take that out. It destroys the mood, and besides, your income is going to change.” So I deleted it. But my salary stayed the same for years. What changed was all the sex I was describing.