Manuel Rodriguez ‘Manolete’ had entered his thirty-first year on July 4th, 1947. His birthplace was Cordoba, a hundred and twenty kilometres down the Guadalquivir from Linares. Since 1939 he had been at the height of his profession; lean, hawk-nosed, and saturnine, he was dubbed ‘The Monster’, and the national idolatry he commanded was greater even than that accorded to Belmonte. The gossips said that the incessant strain of having to be always at his best had lately been driving him to the bottle; Camara, his agent and friend, had confessed that he often seemed a somnambulist, so badly was he weakened by late hours and deep drinking.

On July 16th, fighting unpaid in a charity corrida at Madrid, he had been gored by a Bohorquez bull and, although swaying on his feet, completed the faena and kill before consenting to be carried to the infirmary, where the bull’s ears were brought to him. His convalescence took three weeks and meant the cancellation of six contracts. On August 4th, still groggy, he reappeared at Vitoria, cutting an ear. He fought again in the same town on the 5th, and travelled during the next ten days to Valdepenas, San Sebastian, Huesca, and Gijon; in all four placed he seemed ominously shaky. On the 16th he returned to San Sebastian on the same programme as Luis Miguel, his most serious rival among the younger men, and cut both ears of his first bull. As the cheers died, he was asked by a radio commentator in the callejon to say a few words. He responded laconically: “They ask of me more than I can give. I would say only one thing, and that is that I wish it were October and the season were ended.” He failed in the second bull, and the crowd jeered. That evening he dined with his mother, and then departed for Toledo, where he had a spectacular success on the 17th.

A few days later he gave an interview to a journalist in which he said he had decided to retire at the end of the year. “I am out of temper,” he said. “The public expects more of me every time I appear. It is impossible.” Before a hostile audience in Gijon on the 24th he was lamentably bad, and two days later, at Santander, he heard only mild applause. Meanwhile, the posters were already up in Jaen and Cordoba and the villages of the Guadalsuivir valley, announcing the cartels for the feria at Linares. Two corridas had been organized, in the first of which, fixed for the 28th, Gitanillo de Triana, Manolete, and Luis Miguel would meet six Miura bulls.

On the evening of Wednesday the 27th, Manolete left Madrid by car, accompanied by Camara, a bullfight journalist named Bellon, and Guillermo, his chauffeur-cum-sword-handler. They arrived in Linares soon after dawn next day, having driven all night, and Manolete went straight to his room to rest. At eleven he rose; the hubbub of a town en fête welled up from the streets. He breakfasted lightly on fruit, and received handshakes from a few friends. The fight was timed to begin at five-thirty: around four he put on the suit of lights and, after a few minutes of prayer, rose and faced Camara.

“How are the bulls, Pepe?”

“Fine. Not too big, not too little.”

At five-fifteen he was driven to the bullring, looking as bleak and impassive as always.

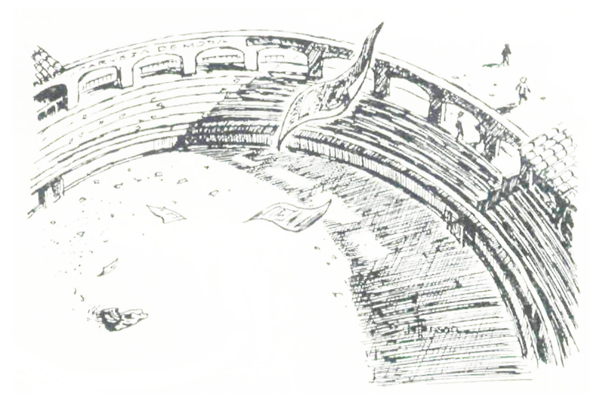

The Plaza de Toros at Linares, officially classified as a second-category ring, holds ten thousand spectators. It was full to overflowing. The three matadors were greeted with an ovation, to acknowledge which Manolete led them out, montera in hand, to the middle of the circle. Gitanillo, a once-brilliant gypsy, two years Manolete’s senior and for many years his friend, took the first Miura. It lacked power, but was frank with the capes, and Gitanillo received scattered applause. The second, Manolete’s, showed even less caste; he gave it a few derechazos in a dangerous terrain and then, seeing that its will was ebbing rapidly, resorted to flashy and meaningless adornos which dismayed the purists in the crowd. He killed with a pinchazo and a forward estocada; “the bull,” says Francisco Narbona in his book Manolete, “deserved no better”; and the audience gently applauded.

Luis Miguel, eager to outdo the maestro, was lucky in a fine third bull. He put in two pairs of sticks himself and brought off a neat faena based on two series of naturals; though he killed less than well, the crowd insisted that an ear be awarded. A slight misunderstanding followed, of a kind all too common in country rings; Luis Miguel’s head peon presented him with both ears and the tail. This over-enthusiasm brought noisy protests, and Luis Miguel had to be content with a single trophy. With the fourth bull Gitanillo was uncertain and took no risks. Then came the fifth.