Issue 138, Spring 1996

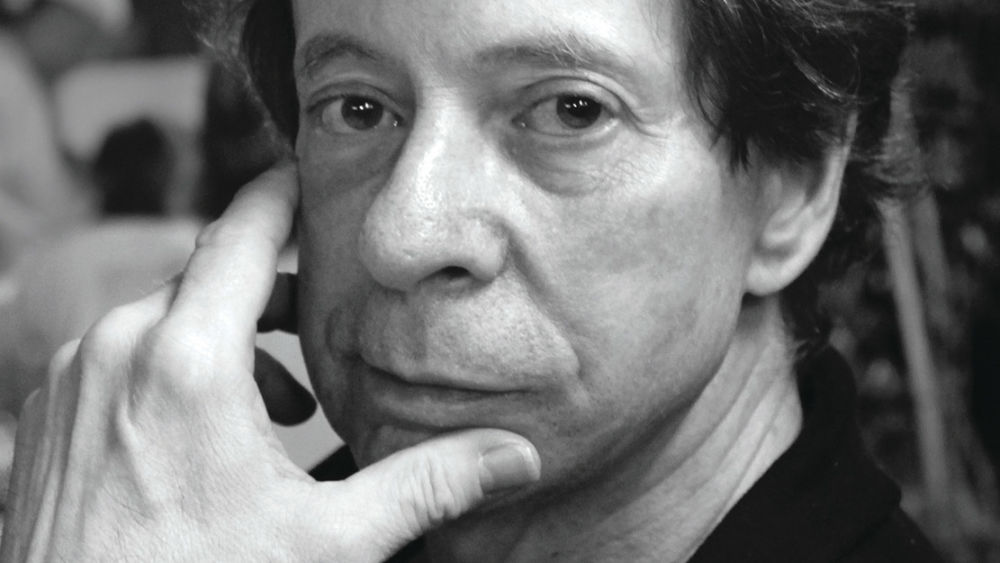

Lorraine Adams/Courtesy of Henry Holt & Co.

Lorraine Adams/Courtesy of Henry Holt & Co.

Richard Price has proven that there can indeed be a third act in the career of an American writer. After a distinguished debut as a novelist, with The Wanderers, and a subsequent literary faltering that led to his recasting himself as a screenwriter of studio-produced movies, Price returned in recent years to fiction with Clockers, a monumental work that is both a murder mystery and a descendant of literary naturalism.

In fact, at the time of this interview, as Price was finishing a spate of screenplays, script-doctoring assignments, and embarking on a new novel, this member of the first generation of writers who grew up as much with television as with books seemed poised to shuttle back and forth between the composition of capacious and highly regarded novels and what is often seen by writers as the devouring maw of the motion-picture industry.

Price’s fiction has always been cinematic. The Wanderers, a novel about an eponymous gang he wrote while in the Columbia University writing program, was an evocation and exaggeration of his childhood in the Bronx housing projects and was made into a film soon after publication. That novel was followed in quick, almost annual, succession by Bloodbrothers, also adapted for the screen, Ladies’ Man, and The Breaks, this last harkening back to his college experience at Cornell.

While contending with a cocaine addiction, having produced two unfinished novels and feeling that he had cannibalized his own life as a subject matter, Price accepted a screenwriting assignment that, though never made into a film, became a kind of calling card. Since then his prolific screen credits include The Color of Money (a 1986 sequel to Robert Rossen’s 1961 film The Hustler that was directed by Martin Scorsese), “Life Lessons,” Martin Scorsese’s half-hour segment for New York Stories (1989), Sea of Love (1989, a quasi-adaptation of his novel Ladies’ Man), Night and the City (a 1992 remake of the Jules Dassin film), Kiss of Death (a remake of the 1947 noir), Mad Dog and Glory, and the forthcoming Ransom.

In researching his movies and finding that worlds beyond his own experience could feed his imagination, Price discovered that “talent travels” and determined to return to the novel. After immersing himself in the diverse lives of Jersey City housing projects, a nightmare version of the terrain of his childhood, he wrote Clockers, which takes its name from lower-echelon crack dealers. In many ways that novel is an answer to the challenge Tom Wolfe laid down in his essay “The Billion-Footed Beast” for writers to enlarge the scope of the novel through engagement in the larger social issues. Clockers was widely recognized as a dispatch from the asphalt combat zone of the American underclass, but Price, having stalled earlier as a novelist, seems prouder of its artfulness.

On meeting Price, one is struck first by his extreme verbal intensity. His earlier career ambition to be a labor lawyer is easy to imagine. Although one might not notice, even after a number of meetings, that Price’s right hand is imperfect—a result of complications during his birth—his physical self-consciousness is apparent and he goes to some effort in managing new acquaintances to avoid shaking hands.

The first two sessions of this interview were conducted in the summer of 1993 at a loft on lower Broadway in New York where Price lived with his wife, Judy Hudson, a talented painter, and their two daughters, a home he would soon be moving from. We conversed in the kitchen area of the open central space. The walls were hung with paintings by Hudson and her contemporaries—Bachelor, Linhares, Taafe.

Price has since moved to a new home, where the third session of this interview took place. He now lives in a brownstone near Gramercy Park, which still bears many effects from a previous owner, a member of FDR’s brain trust, who decorated it with Art Deco details, including a bathroom featuring huge double bathtubs and a deep-sea motif. In the living room hangs one of the better examples of Julian Schnabel’s work—a gift for Price’s consulting on the script of that artist’s forthcoming biopic of Jean Michel Basquiat.

The whole suggests a place decorated with the grace and tasteful eye of downtown artists into whose lives a great deal of money has recently flowed. During the interview, signs of the couple’s young daughters were in evidence; twice they buzzed on an intercom to demand, not without charm, the family’s video-account rental number. Friends of the couple had remarked that Judy Hudson was the secret to Price; attractive, accessible and funny, she seemed surprisingly uncomplicated for an artist.

Price’s office, the first he has had in the place he lives, is dominated at one end by a large desk where he writes, at the other by a fireplace blocked with the poster of the movie Clockers. A large Chinese box. A many-drawered chest, like an old typesetter’s case. A Jonathan Borofsky print. A Phillip Guston print. A Sugimoto photo of a theater screen, with a proscenium decorated by Botticelli’s Venus on a Half Shell. Leaning against a wall is an Oscar-nomination certificate for his screenplay of The Color of Money. Price says, “You’re supposed to hang that in the bathroom where everyone who comes to your home will be forced to stare at it and see how, since you keep it there, you don’t take it very seriously.”

One senses that the writer is proud of the domesticity he has achieved, but that he is not particularly attached to the material objects of the world he and his family have created. At the center of the room is a coffee table surrounded by a couch and chairs—on its surface as if arranged for inspection, are three stacks of Day-Glo orange notebooks, the startling color of a traffic cop’s safety vest. Placed before the notebooks, front and center, is a typescript, shy of a hundred pages. As Price sits down to talk, he glances intently for a moment at the novel in progress perhaps to reassure himself that it is still there.

INTERVIEWER

What started you writing?

RICHARD PRICE

Well, my grandfather wrote poetry. He came from Russia. He worked in a factory, but he had also worked in Yiddish theater on the Lower East Side of New York as a stagehand. He read all the great Russian novelists and he yearned to say something. He would sit in his living-room chair and make declarations in this heavy European accent like, When the black man finally realizes what was done to him in this country . . . I don’t wanna be here. Or, If the bride isn’t a virgin, at some point in the marriage there’s gonna be a fight, things will be said . . . and there’s gonna be no way to fix the words.

I mean I didn’t even know what a virgin was but I felt awed by the tone of finality, of pronouncement. He wrote little stories, prose poems in Yiddish; my father translated them into English and they’d be published in a YMHA journal in Brooklyn. I remember a story about a dying wife, a husband’s bedside vigil, a glittering candle. The candle finally goes out the minute the wife draws her last breath. He was kind of like the O. Henry Miller of Minsk. I was seven, eight years old and I was fascinated by the idea of seeing my grandfather’s name and work on a printed page. Later, in college, I always went for the writing classes. I’d get up at these open readings at coffeehouses, read these long beat/hippy things and get a good reaction from people. It was like being high. Back then, I would take a story, break it up arbitrarily, and call it a poem. I had no idea where to break anything. Rhythm, meter, I didn’t know any of this stuff. I just had a way with words and I also had a very strong visceral reaction to the applause that I would get.

INTERVIEWER

Were books an influence?

PRICE

The books that made me want to be a writer were books like Hubert Selby’s Last Exit to Brooklyn, where I recognized people who were somewhat meaner and more desperate than the people I grew up with, but who were much closer to my own experience than anything I’d ever read before. I mean, I didn’t have a red pony. I didn’t grow up in nineteenth-century London. With Last Exit to Brooklyn, I realized that my own life and world were valid grounds for literature, and that if I wrote about the things that I knew it was honorable—that old corny thing: I searched the world over for treasures, not realizing there were diamonds in my own backyard.

INTERVIEWER

How old were you when you read Last Exit?

PRICE

I was sixteen or seventeen. I was a major screwup in school, but I always read. Libraries. Paperbacks. I read City of Night and all the Evergreen and Grove Press stuff. I read a lot of horror stuff. I read Steinbeck. Although my experience wasn’t Okie, rural, there was something in the simplicity of his prose that was very seductive. It made me feel that I didn’t have to construct sentences like a nineteenth-century Englishman to be a writer.

INTERVIEWER

You intended to go to law school, but you ended up a writer . . .

PRICE

I always wanted to be a writer, but coming from a working-class background it was hard to feel I had that right. If you’re the first generation of your family to go to college, the pressure on graduation is to go for financial security. The whole point of going to college is to get a job. You have it drilled into your head—job, money, security. Wanting to be an artist doesn’t jibe with any of those three. If you go back to these people who have “slaved and sacrificed” to send you to school, who are the authority figures in your life, and you tell them that you want to be a writer, a dancer, a poet, a singer, an actor, and to do so you’re going to wait tables, drive a cab, sort mail, with your Cornell University degree, they look at you like you’re slitting their throats. They just don’t have it in their life experience to be supportive of a choice like that.

Because I came from that kind of background, it was a scary decision not to go to law school. Maybe one reason The Wanderers got the attention it did was that nobody coming from my background with such an intimate knowledge of white housing-project life was writing about it. The smartest minds of my generation in the projects became doctors, lawyers, engineers, businessmen; they went the route that would fulfill the economic mandate.

INTERVIEWER

Had you ever met a writer before you decided to be one?

PRICE

At Cornell the class of 1958 or 1959 was amazing—with Richard Farina, Ronald Sukenick, Thomas Pynchon, Joanna Russ, Steve Katz, all of whom are working writers now in various degrees of acclaim or obscurity. When I was at Cornell from 1967 to 1971 two or three of them came back to teach. It was the first time I sat in a room with a teacher who wasn’t as old as my father. Here was a guy wearing a vest over a T-shirt. He had boots on, and his hair was longer than mine. A novelist! I couldn’t take my eyes off him. I felt, Ah, to be a writer! I could be like this teacher and have that long, gray hair . . . boots up on the table and cursing in class! It made me dizzy just to look at the guy. I don’t remember a thing he said to me, except that he usually made encouraging noises: You’re good. You’re okay, keep writing, blah, blah . . . He gave us this reading list that ranged from Céline to Walter Abish to Mallarmé and Rimbaud, names I’d never even heard of. The books looked so groovy, so cool, and so hip. I bought every one of them. I walked around with Alfred Jarry and Henri Michaux under my arm, but I didn’t understand what they were trying to do, to say. I had no context for any of them. The only one I could get through on the list was Henry Miller. One writing teacher gave us his own novel and, frankly, I couldn’t understand that either.

INTERVIEWER

What kinds of things did you write for him?

PRICE

I had a talent for making ten-page word soufflés that were sort of tasty. In the late sixties anything went. Everybody was an artist in the late sixties. Sort of like punk music in the seventies.