Issue 120, Fall 1991

Donald Hall was born in New Haven and raised in Hamden, Connecticut, but spent summers, holidays, and school vacations on a farm owned by his maternal grandparents in Wilmot, New Hampshire. He took his bachelor’s degree at Harvard, then studied at Oxford for two years, earning an additional bachelor’s in 1953. After holding fellowships at Stanford and at Harvard, Hall moved to Ann Arbor, where he was professor of English at the University of Michigan for seventeen years. His first book of poems, Exiles and Marriages (1955), was followed by The Dark Houses (1958), A Roof of Tiger Lilies (1964), The Alligator Bride: New and Selected Poems (1969), The Yellow Room (1971), The Town of Hill (1975), Kicking the Leaves (1978), The Happy Man (1986), The One Day (1988), and Old and New Poems (1990).

He is also the author of several books of prose, some written for students, some for children, and some for sports fans. They include biographies of Henry Moore and Dock Ellis, a reminiscence called Remembering Poets (about Frost, Pound, Thomas, and Eliot), and four collections of literary essays: Goatfoot Milktongue Twinbird (1978), To Keep Moving (1980), The Weather for Poetry (1982), and Poetry and Ambition (1988). Two of the anthologies he has compiled have become classics: New Poets of England and America (with Robert Pack and Louis Simpson) and Contemporary American Poetry. Among other honors, he has received the Lamont Poetry Selection Award (for Exiles and Marriages) and two Guggenheim Foundation Fellowships (1963, 1972). His children’s book, Ox-Cart Man (1980), illustrated by Barbara Cooney, won the Caldecott Award. He was the first poetry editor of The Paris Review, from 1953 to 1961, as well as the first person to interview a poet for this magazine.

In 1975, after the death of his grandmother, Hall gave up his tenured professorship at Michigan and moved with his wife Jane Kenyon to the old family farm in New Hampshire. Since then he has supported himself through freelance writing. Sixteen years later, he continues to feel that he never made a better decision. It was at Eagle Pond Farm that the first two sittings of this interview were conducted in the summers of 1983 and 1988. A third session was held on the stage of the YM-YWHA in New York.

Donald Hall likes to get to work early, and so both interview sessions at the farm began at about six a.m. Interviewer and interviewee sat in easy chairs with the tape recorder on a coffee table between them.

INTERVIEWER

I would like to begin by asking how you started. How did you become a writer? What was the first thing that you ever wrote and when?

DONALD HALL

Everything important always begins from something trivial. When I was about twelve I loved horror movies. I used to go down to New Haven from my suburb and watch films like Frankenstein, The Wolf Man, The Wolf Man Meets Abbott and Costello. So the boy next door said, Well, if you like that stuff, you’ve got to read Edgar Allan Poe. I had never heard of Edgar Allan Poe, but when I read him I fell in love. I wanted to grow up and be Edgar Allan Poe. The first poem that I wrote doesn’t really sound like Poe, but it’s morbid enough. Of course I have friends who say it’s the best thing I ever did: “Have you ever thought / Of the nearness of death to you? / It reeks through each corner, / It shrieks through the night, / It follows you through the day / Until that moment when, / In monotones loud, / Death calls your name. / Then, then, comes the end of all.” The end of Hall, maybe. That started me writing poems and stories. For a couple of years I wrote them in a desultory fashion because I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to be a great actor or a great poet.

Then when I was fourteen I had a conversation at a Boy Scout meeting with a fellow who seemed ancient to me; he was sixteen. I was bragging and told him that I had written a poem during study hall at high school that day. He asked—I can see him standing there—You write poems? and I said, Yes, do you? and he said, in the most solemn voice imaginable, It is my profession. He had just quit high school to devote himself to writing poetry full time! I thought that was the coolest thing I’d ever heard. It was like that scene in Bonnie and Clyde where Clyde says, We rob banks. Poetry is like robbing banks. It turned out that my friend knew some eighteen-year-old Yale freshmen, sophisticated about literature, and so at the age of fourteen I hung around Yale students who talked about T. S. Eliot. I saved up my allowance and bought the little blue, cloth-covered collected Eliot for two dollars and fifty cents and I was off. I decided that I would be a poet for the rest of my life and started by working at poems for an hour or two every day after school. I never stopped.

INTERVIEWER

What about at your high school? I believe you attended Exeter—was anyone there helpful to you?

HALL

After a couple of years of public high school, I went to Exeter—an insane conglomeration of adolescent males in the wilderness, all of whom claimed to hate poetry. There was support from the faculty—I dedicated A Roof of Tiger Lilies to one teacher and his wife, Leonard and Mary Stevens—but of course there was also discouragement. One English teacher made it his announced purpose to rid me of the habit of writing poetry. This was in an English Special, for the brightest students, and he spent a fifty minute class reading aloud some poetry I’d handed him, making sarcastic comments. For the first ten minutes, the other students laughed—but then they shut up. They may not have liked poetry but they were shocked by what he did. When I came back to Exeter ten years later to read my poems, after publishing my first book, the other teachers asked my old teacher-enemy to introduce me and my mind filled up with possibilities for revenge. I did nothing of course, but another ten years after that apparently my unconscious mind did exact its revenge—and because I didn’t intend it, I could enjoy revenge without guilt. I wrote an essay for The New York Times Book Review that offered a bizarre interpretation of Wordsworth’s poem about daffodils. At the end, I said that if anyone felt that my interpretation hurt their enjoyment of the poem, they’d never really admired the poem anyway, but just some picture postcard of Wordsworth’s countryside that a teacher handed around in a classroom. When I wrote it, I thought I made the teacher and his classroom up, but a few days after the piece appeared, I received the postcard in an envelope from my enemy-teacher at Exeter together with a note: I suppose your fingerprints are still on it.

INTERVIEWER

Was there anyone else when you were young who encouraged you to be a writer?

HALL

Not really. My parents were willing to let me follow my nose, do what I wanted to do, and they supported my interest by buying the books that I wanted for birthdays and Christmas, almost always poetry books. When I was sixteen years old I published in some little magazines and my parents paid for me to go to Bread Loaf.

I remember the first time I saw Robert Frost. It was opening night and Theodore Morrison, the director, was giving an introductory talk. I felt excited and exalted. Nobody was anywhere near me in age; the next youngest contributor was probably in her mid-twenties. As I was sitting there, I looked out the big French windows and saw Frost approaching. He was coming up a hill and as he walked toward the windows first his head appeared and then his shoulders as if he were rising out of the ground. Later, I talked with him a couple of times and I heard him read. He ran the poetry workshop in the afternoon on a couple of occasions, though not when my poems were read, thank God; he could be nasty. I sat with him one time on the porch as he talked with two women and me. He delivered his characteristic monologue—witty, sharp, acerb on the subject of his friends. He wasn’t hideously unkind, the way he looks in Thomson’s biography, but also he was not Mortimer Snerd; he was not the farmer miraculously gifted with rhyme, the way he seemed if you read about him in Time or Life. He was a sophisticated fellow, you might say.

We played softball. This was in 1945, and Frost was born in 1874, so he was seventy-one years old. He played a vigorous game of softball but he was also something of a spoiled brat. His team had to win and it was well known that the pitcher should serve Frost a fat pitch. I remember him hitting a double. He fought hard for his team to win and he was willing to change the rules. He had to win at everything. Including poetry.

INTERVIEWER

What was the last occasion on which you saw him?

HALL

The last time I saw him was in Vermont, within seven or eight months of his death. He visited Ann Arbor that spring and invited me to call on him in the summer. We talked about writing, about literature—though of course mostly he monologued. He was deaf, but even when he was younger he tended to make long speeches. Anyway, after we had been talking for hours, my daughter Philippa, who was three years old, asked him if he had a TV. He looked down at her and smiled and said, You’ve seen me on TV?

Also we talked about a man—another poet I knew—who was writing a book about Frost. Frost hadn’t read his poetry and he asked me, Is he any good? I told him what I thought. Then, as we were driving away, I looked into the rearview mirror and saw the old man, eighty-eight, running after the car—literally running. I stopped and he came up to the window and asked me please, when I saw my friend again, not to mention that Frost had asked me if his poetry was any good, because he didn’t want my friend to know that he had not read his poetry. Frost was a political animal in the literary world. So are many of the best poets I run into and it doesn’t seem to hurt their poetry.

INTERVIEWER

Our meeting is an occasion of sorts since you are the original interviewer of poets for The Paris Review. Whom did you interview?

HALL

T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Marianne Moore. I had already known Eliot for a number of years. At the time of the interview, he was returning from a winter vacation in someplace like the Bahamas and we did the interview in New York. He looked tan and lean and wonderful, which surprised me. I had not seen him then for two or three years, and in the meantime he had married Valerie Fletcher. What a change in the man! When I first met him in 1950, he looked like a corpse. He was pale and bent over; he moved stiffly and slowly and coughed a continual, hacking cough. This ancient character was full of kindness and generosity, but he looked ready for the grave, as he did the next several times I saw him. Then, when I met him for the interview after his happy second marriage, he looked twenty years younger. He was happy; he giggled; he held hands with his young wife whenever they were together. Oh, he was an entirely different person, lighter and more forthcoming. Pound I interviewed in the spring of 1960. I was apprehensive, driving to see him in Rome, because I was afraid of what I’d run into. I had loved his poetry from early on but his politics revolted me, as they did everybody. The Paris Review had scheduled an interview with him once before when he was at St. Elizabeth’s, but he canceled at the last minute because he determined that The Paris Review was part of the “pinko usury fringe.” That’s the sort of thing I expected, but that’s not what I found. He was staying with a friend in Rome and I drove down from England with my family. After I had knocked on the door and he swung it open and made sure it was me, he said, Mr. Hall, you’ve come all the way from England—and you find me in fragments! He spoke with a melody that made him sound like W. C. Fields. There’s the famous story—this didn’t happen to me but I love it—of a young American poet who was wandering around in Venice, not long before Pound died, and recognized the house where Pound was living with Olga Rudge. Impulsively, he knocked on the door. Maybe he expected the butler to answer, but the door swung open and it was Ezra Pound. In surprise and confusion the young poet said, How are you, Mr. Pound? Pound looked at him and, as he swung the door shut, said, Senile.

The Pound I interviewed in 1960 had not yet entered the silence, but the silence was beginning to enter him. There were enormous pauses in the middle of his sentences, times when he lost his thread; he would begin to answer, then qualify it, then qualify the qualification, as though he were composing a Henry James sentence. Often he could not find his way back out again and he would be overcome with despair. He had depended all his life on quickness of wit and sharpness of mind. It was his pride. Now he was talking with me for a Paris Review interview, which he took seriously indeed, and he found himself almost incapable. Sometimes after ten minutes of pause, fatigue, and despair, he would heave a sigh, sit up, and continue the sentence where he had broken it off. He was already depressed, the depression that later deepened and opened that chasm of silence. But then and there in 1960 I had a wonderful time with him. He was mild, soft, affectionate, sane. One time he and I went across the street to have a cup of coffee at a café where I had had coffee earlier. The waiter recognized us both, though he had never before seen us together, and thought he made a connection. He spoke a sentence in Italian that I didn’t understand, but the last word was figlio. Pound looked at me and looked at the waiter and said, Si.

INTERVIEWER

In the interview with him, your questions are challenging yet he seems, not evasive exactly, but as though he just did not quite understand what he had done.

HALL

Oh, no, he never really understood. He insisted that there could be no treason without treasonable intent. I’m certain that he had no treasonable intent, but if treason is giving aid and comfort to the enemy in time of war, well . . . he broadcast from Rome to American troops suggesting that they stop fighting. Of course he thought he was aiding and comforting the real America. He wasn’t in touch with contemporary America, not for decades. All the time he was at St. Elizabeth’s he was in an asylum for the insane, and his visitors were mostly cranks of the right wing. The news he heard was filtered. I think you can chart his political changes right from the end of the First World War and find that they correlate with the growth of paranoia and monomania that connected economics—finally, Jewish bankers—with a plot to control the world. He started out cranky and moved from cranky to crazy.

INTERVIEWER

In Remembering Poets, just as now, the one poet you interviewed that you don’t talk about is Marianne Moore.

HALL

Back then, I thought I didn’t have enough to say—or enough that other writers hadn’t already said. Lately, I’ve come up with some notions about her that I may write up for a new edition of that book. I had lunch with her twice in Brooklyn. The first time she took me up the hill to the little Viennese restaurant where she took everybody. Like everybody else I fought with her for the check and lost. She was tiny and frail and modest, but oh so powerful. I think she must have been a weight lifter in another life—or maybe a middle linebacker. Whenever you’re in the presence of extreme modesty or diffidence, always look for great degrees of reticent power or a hugely strong ego. Marianne Moore as editor of the Dial was made of steel. To wrestle with her over a check was to be pinned to the mat.

Another time when I came to visit, her teeth were being repaired so she made lunch at her apartment. She thought she looked dreadful and wouldn’t go outside the house without a complete set of teeth. Lunch was extraordinary! On a tray she placed three tiny paper cups and a plate. One of the cups contained about two teaspoons of V-8 juice. Another had about eight raisins in it, and the other five and a half Spanish peanuts. On the plate was a mound of Fritos, and when she passed them to me she said, I like Fritos. They’re so good for you, you know. She was eating health foods at the time, and I’m quite sure she wasn’t being ironic. She entertained some notion that Fritos were a health food. What else did she serve? Half a cupcake for dessert, maybe? She prepared a magnificent small cafeteria for birds.

INTERVIEWER

Marianne Moore went to school and she wrote poetry, but she did not study creative writing in school. Do you think the institution of the creative writing program has helped the cause of poetry?

HALL

Well, not really, no. I’ve said some nasty things about these programs. The Creative Writing Industry invites us to use poetry to achieve other ends—a job, a promotion, a bibliography, money, notoriety. I loathe the trivialization of poetry that happens in creative writing classes. Teachers set exercises to stimulate subject matter: Write a poem about an imaginary landscape with real people in it. Write about a place your parents lived in before you were born. We have enough terrible poetry around without encouraging more of it. Workshops make workshop-poems. Also, workshops encourage a kind of local competition, being better than the poet who sits next to you—in place of the useful competition of trying to be better than Dante. Also, they encourage a groupishness, an old-boy and -girl network that often endures for decades.

The good thing about workshops is that they provide a place where young poets can gather and argue—the artificial café. We’re a big country without a literary capital. Young poets from different isolated areas all over the country can gather with others of their kind.

And I suppose that workshops have contributed to all the attention that poetry’s been getting in the last decades. Newspaper people and essayists always whine about how we don’t read poetry the way we used to—in the twenties, for example. Bullshit! Just compare the numbers of books of poems sold then and now. Even in the fifties, a book of poems published by some eminent poet was printed in an edition of a thousand hardback copies. If it sold out everyone was cheerful. In 1923 Harmonium didn’t sell out—Stevens was remaindered, for heaven’s sake! A book of poetry today by a poet who’s been around will be published in an edition of five to seven thousand copies and often reprinted.

But it’s not the Creative Writing Industry itself that sells books; it’s the poetry readings. Practically nobody in the twenties and thirties and forties did readings. Vachel Lindsay, early, then Carl Sandburg, then Robert Frost—nobody else. If you look at biographies of Stevens and Williams and Moore, you see that they read their poems once every two years if they were lucky. Poetry readings started to grow when Dylan Thomas came over in the late forties and fifties. By this time there are three million poetry readings a year in the United States. Oh, no one knows how many there are. Sometimes I think I do three million a year.

In the sixties when the poetry reading boom got going people went to their state universities and heard poets read. When they went back to their towns they got the community college to bring poets in or they set up their own series through an arts group. Readings have proliferated enormously and spread sideways from universities to community colleges, prep schools, and arts associations. I used to think, Well, this is nice while it lasts but it’ll go away. It hasn’t gone away. There are more than ever.

INTERVIEWER

We were talking about your Paris Review interviews. You also edited poetry for the Paris Review for nine years at the beginning of the magazine. Why did you want to edit?

HALL

At that time I was a fierce advocate of the contemporary, with huge dislikes and admirations, and I wanted to impose my taste. That’s why I did the Advocate at Harvard, why I did The Paris Review, why I did anthologies. When I was at Oxford, besides choosing poetry for The Paris Review, I edited a mimeographed sheet for the Poetry Society; another magazine called New Poems; the poetry in the weekly, Isis; and Fantasy Poets, a pamphlet series that was started by a surrealist painter who did printing on the side. Michael Shanks edited the first four Fantasy pamphlets—including mine—and when Shanks went down to London, I chose the second bunch, which included Geoffrey Hill and Thom Gunn.

Oxford was a good time, though I felt rather elderly at Oxford. At Harvard I was a year younger than John Ashbery even, but at Oxford I was older than everybody. I’d been through college, while most of them were just out of boarding school. I had fun being dogmatic and bossy. Over at Cambridge, where there hadn’t been any poets for years, Thom Gunn turned up writing those wonderful early poems. When we heard him on the BBC, we invited him over to Oxford. My greatest time as an editor was with Geoffrey Hill. Just before the end of my first year at Oxford, he published a poem in Isis—a poem he’s never reprinted. Meeting him, I asked him casually if he’d submit a manuscript to the Fantasy series. Then I came back to the States for the summer; I was here in New Hampshire when Geoffrey’s manuscript arrived. I couldn’t believe my eyes: “Genesis,” “God’s Little Mountain,” “Holy Thursday.” Extraordinary! In the middle of the night I woke up dreaming about it; I turned on the light and read it again.

I accepted the manuscript for the pamphlet series. Later I put “Genesis” in the second issue of The Paris Review. Geoffrey was twenty years old.

INTERVIEWER

I believe you were known for a period in the sixties as James Dickey’s editor or even as his discoverer.

HALL

Oh, I was not his discoverer, but I did publish him early. When I was editing for The Paris Review I got poems from an address in Atlanta—long, garrulous poems with good touches. After a while I started writing notes, maybe “sorry” on a printed slip, then “thank you,” then a letter saying “I don’t like the middle part.” Finally he sent a poem I liked and I took it. We began to correspond and I discovered that he was in advertising. He sent me a fifteen-second radio ad for Coca-Cola, saying, This is my latest work.

When I was on the poetry board at Wesleyan, he sent us a book, I think at Robert Bly’s urging. But we took two other books ahead of him—we could only do two every season—and one of them was going to be James Wright’s third book, which he was calling “Amenities of Stone.” These two books crowded James Dickey out, which was a pity because it was Drowning with Others—his best work, I still think. Maybe two months later, my phone rang one morning at about seven a.m. It was Willard Lockwood, director of the Wesleyan University Press, saying that Jim Wright had withdrawn his book. Wesleyan was about to go to press; there was no time for the committee to meet again. Would it be all right to substitute the runner-up book, which was James Dickey’s? I called Dickey in Atlanta, then and there, seven-thirty in the morning, and asked, Has your book been taken by another publisher? Can we still have it? He said to go right ahead. So Wesleyan published James Dickey because James Wright withdrew his book.

INTERVIEWER

Did you get to know James Dickey?

HALL

I think I first met him out at Reed College when he was teaching there for a semester. Poetry got him out of advertising and for a while he traveled from school to school, one year here and another year there. I’m not sure which year he spent at Reed—early sixties—but we had a good visit out there. Carolyn Kizer came down from Seattle. Jim and I drove around in his MG, talking. He was friendly, and flattering about my work, but I began to notice—because of things he said about other people—that loyalty might not be his strong point. So I asked him straight out, Don’t you think loyalty’s a great quality? He knew what I was up to; he said, No, I think it’s a terrible quality. I think it’s the worst quality there is.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s move away from editing other people to editing yourself. Could you talk about how you work? I gather that you revise a lot.

HALL

First drafts of anything are difficult for me. I prefer revising, rewriting. I’m not the kind of writer like Richard Wilbur or Thomas Mann who finishes one segment before going on to another. Wilbur finishes the first line before he starts the second. I lack the ability to judge myself except over many drafts and usually over years. Revising, I go through a whole manuscript over and over and over. Some short prose pieces I’ve rewritten fifteen or twenty times; poems get up to two hundred fifty or three hundred drafts. I don’t recommend it, but for me it seems necessary. And I do more drafts as I get older.

Or maybe I just like it. Even with prose, I love the late stage in rewriting. I play with sentences, revise their organization, work with the rhythms, work with punctuation as though I were handling line breaks in poetry. In poetry I play with punctuation, line breaks, internal sounds, interconnections among images. I tinker with little things, and it’s my greatest pleasure in writing.

INTERVIEWER

Do you generally have several things going at once?

HALL

I’m not good at working on one thing straight through. When I work more than an hour on one project, I get irritated. Or sometimes I get too high. I spend my day working on many different things, never so long as an hour. When I get stuck, I put it down. Maybe I go haul some wood or have a drink of water; then I come back and pick up something else—an essay I’m working on, a book that’s due in six months . . . I work on poems usually in one block of time for an hour or two hours—recently sometimes three hours; things have been hotting up—almost always on several poems.

It isn’t just alternating projects; I switch around among genres and I work in many: children’s books, magazine pieces, short stories, textbooks. Obviously I care about poetry the most. But I love working with various kinds of prose also, even something as mundane as headnotes for an anthology. After all, I am working with the same material—language, syntax, rhythms and vowels—as if I were a sculptor who worked at carving in stone all morning and then in the afternoon built drywalls or fieldstone houses.

There’s pleasure in doing the same thing in different forms. When I heard the story of the oxcart man from my cousin Paul Fenton, I started work on a poem. It’s a wonderful story, passed on orally for generations until I stole it out of the air: A farmer fills up his oxcart in October with everything that the farm has produced in a year that he doesn’t need—honey, wool, deerskin—and walks by his ox to Portsmouth market where he sells everything in the cart. Then he sells the cart, then the ox, and walks home to start everything over again.

The best stories come out of the air. I worked on that oxcart man poem, brief as it is, for about two years. Just as I was finishing it, I suddenly thought that I could make a children’s book out of the same story. The children’s book took me a couple of hours to write—hours not years—and the wage was somewhat better. When the book won the Caldecott, we were able to tear off the dingy old bathroom and put a new bathroom into an old bedroom and add a new bedroom; over the new bathroom I have a plaque: Caldecott Room.

Later I used the same oxcart story as part of an essay and as a song that Bill Bolcom set for Joan Morris to sing. Now I’ve used it again, here in an interview! Every time I tell the story it’s different. The form makes it different, also the audience, and therefore the tone, therefore the diction—which makes the whole process fascinating. In working on a play I used material from all over the place: from one prose book in particular, from other essays, from fiction, from poems. When I put these things into bodily action and into dialogue on a stage—material that I had already used up, you might have thought—they take on new life, thanks to the collision with a different genre.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned sculpture a few minutes ago. What is it about Henry Moore that so fascinates you?

HALL

I had admired his work for a long time before I had the chance to interview him for Horizon. When I was an undergraduate I pinned a Penguin Print of Henry Moore’s sculpture on my wall. When I first got to England in 1951 I saw his sculpture at the Festival of Britain. It was 1959 when I met him and interviewed him; three years later I came back and hung around him for a whole year—watching, listening—to do a New Yorker profile, which later became a book. Of all the older artists I’ve known, he’s made the most difference for my own writing. He helped me get past a childish form of ambition: the mere striving to be foremost. He wasn’t interested in being the best sculptor in England or even the best sculptor of his generation. He wanted to be as good as Michelangelo or Donatello. He was in his early sixties when I met him first—my age now—and oh, he loved to work! At the same time he was a gentle, humorous, gregarious man. He got up early every morning—and he got on with it. I think of a story from the time when he and Irina were first married. They were going off into the country for a holiday, and Irina tried to lift one of the suitcases that Henry had brought but she couldn’t get it off the ground. He’d packed a piece of alabaster. I am sure that they paid lots of attention to each other, but from time to time Henry went outside and tap-tapped with chisel and mallet.

I loved hearing him talk about sculpture, and everything he said about sculpture I turned to poetry. He quoted Rodin quoting a craftsman: never think of a surface except as the extension of a volume. I did a lot with that one.

INTERVIEWER

Did you envy him for the physicality of his materials?

HALL

The physical activity of the painter and the sculptor keeps them in touch with the nature of their art more than writing does for writers. Handwriting or typing or word processing—they’re not like sticking your hands into clay.

Yet a poem has a body, just as sculpture and painting have bodies. When you write a poem, you’re not hammering out the sounds with a chisel or spreading them with a brush, but you’ve got to feel them in your mouth. The act of writing a poem is a bodily act as well as a mental and imaginative act, and the act of reading a poem—even silently—must be bodily before it’s intellectual. In talking or writing about poetry, too often people never get to the work of art. Instead they talk about some statement they abstract from the work of art, a paraphrase of it. Everybody derides paraphrase and everybody does it. It’s the fallacy of content—the philosophical heresy.

INTERVIEWER

You were talking about writing prose. Tell us more about the relationship between your poetry and your prose.

HALL

When I was young I wrote prose but I didn’t take it seriously; it was terrible. I began to write real prose when I wrote String Too Short to Be Saved, mostly in 1959 and 1960; with that book I learned how to write descriptive and narrative reminiscence. Over the years, I’ve learned how to write other prose—to write for five-year-olds, stories for picture books; to write articles or reviews about poetry; to write prose for popular magazines, some of it objective or biographical, like my profile of Henry Moore; and to write about sports. Also I’ve written short stories, combining narrative prose with some of the shapeliness of poems. Writing prose for a living—freelance writing—does another thing I like: it opens doors. Sir Kenneth Clark had me to lunch at his castle in Kent—because I was writing about Moore for The New Yorker. By sports writing, I made the major leagues, talking with Pete Rose and sitting up half the night with Willie Crawford. I’ve listened to the free association of Kevin McHale of the Boston Celtics.

INTERVIEWER

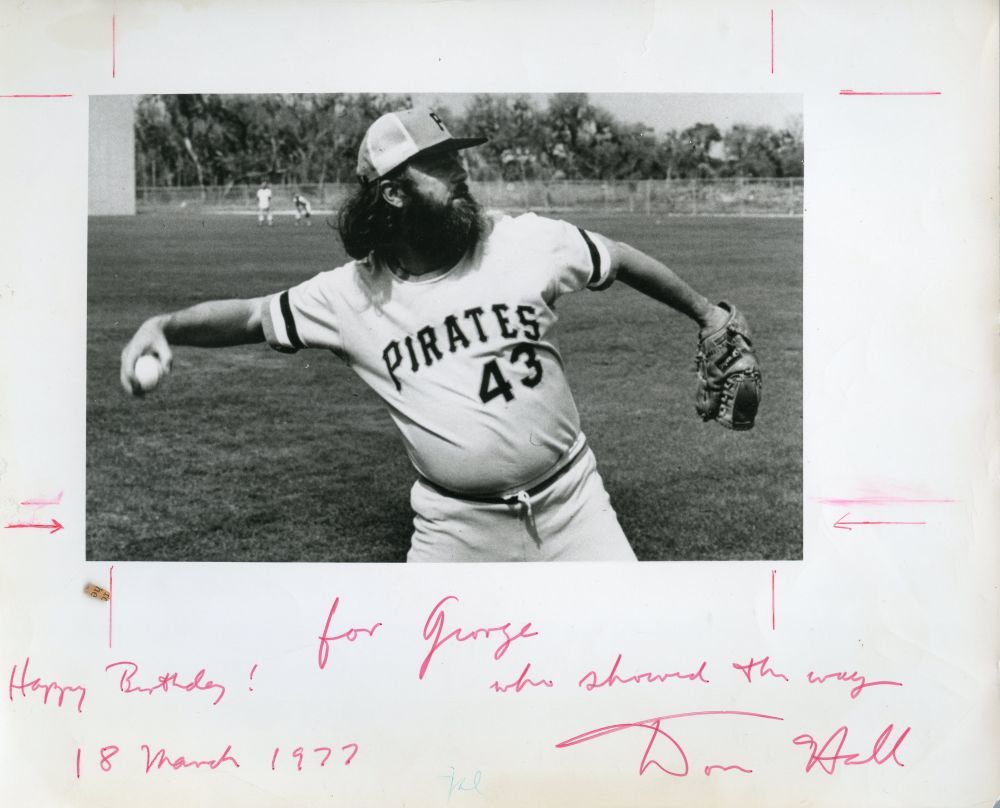

How did the baseball players accept you? As I remember, when you tried out for the Pirates you were bearded and, shall we say, a touch overweight?

HALL

I was bearded and weighed about two hundred fifty pounds when I tried out for second base with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Willie Randolph and Rennie Stennett both beat me out. (I was cut for not being able to bend over, which wasn’t fair; Richie Hebner made the team at third base and he couldn’t bend over either.) The players had nicknames for me, like Abraham and Poet, and they treated me like a mascot. When I took batting practice, the whole team stopped whatever it was doing to watch—the comedy act of the decade. The players looked at me as some sort of respite from their ordinary chores; they were curious, and they were kind enough as they teased me. Mostly, athletes are quick-witted and funny, with maybe a ten-second attention span.

Back to the question: there are several relationships between my prose and my poetry. Prose is mostly the breadwinner. Poetry supplies bread through the poetry reading, but prose makes the steady income. I get paid for an essay once when it comes out in a magazine, then again when I collect it in a book. But also, I think that prose takes some of the pressure off my poetry. Maybe I am able to be more patient with my poetry—taking years and years to finish poems—because I continue to finish and publish short prose pieces.

Prose is tentative and exploratory and not so intense; in prose I can dwell on something longer, not just pick out the one thing to notice or say. Poetry is the top of the mountain. I like the foothills just fine—as long as I keep access to the top of the mountain.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever learned from critics?

HALL

Sure. When I was young, critics helped teach me to read poems. Then critics or poets-being-critics have—in person and by letter—led me to discard poems or to rip them up and start over again. I seek their abrasiveness out. I’ve even been helped by book reviews, mostly by some general dissatisfaction with my work. But if a book review is a personal attack—someone obviously hates you—it doesn’t do any good. You just walk up and down feeling the burden of this death ray aimed at you. The critics who help have been annoyed with my work and make it clear why without actually wanting to kill me. They give me new occasions for scrutiny, for crossing out.

INTERVIEWER

Another subject. You’re notorious for answering letters. Is your heavy correspondence related to your art? Doesn’t it get in the way?

HALL

Sometimes I wonder, Do I write a letter because it’s easier than writing a poem? I don’t think so. Letters take less time than parties or lunches. How do people in New York get anything done? My letters are my society. I carry on a dense correspondence with poets of my generation and younger. Letters are my café, my club, my city. I am fond of my neighbors up here, but for the most part they keep as busy as I do. We meet in church, we meet at the store, we gossip a little. We don’t stand around in a living room and chat—like the parties I used to go to in Ann Arbor. I write letters instead, and mostly I write about the work of writing. There are poets with whom I regularly exchange poems, soliciting criticism. I don’t think that either Robert Bly or I has ever published a poem without talking it over with the other. Also, I work out ideas in letters, things that will later be parts of essays. I dictate; it takes too much time to type and no one can read my handwriting.

INTERVIEWER

Let me ask a typical Paris Review question: Do you write your poems in long hand? On a typewriter? Or a word processor? Do you use a pen? A pencil?

HALL

For thirty or thirty-five years, I’ve written in longhand—pencil, ballpoint, felt tip, fountain pen; the magic moves around. I used to work at poetry on a typewriter, but I tended to race on, to be glib, not to pause enough. Thirty years ago I gave up the keyboard, began writing in long hand, and hired other people to type for me. At the moment four typists help me out, and one right down the road has a word processor. It’s marvelous because I can tinker without worrying about the time and labor of retyping. I make little changes in ongoing poems every day and start with clean copies every morning.

I dictate letters but nothing else. It irritates me that Henry James was able to dictate The Ambassadors but I can’t dictate the first draft of a book review.

INTERVIEWER

Were you ever part of a group of poets? Did you visit Robert Bly’s farm in the early sixties in Madison, Minnesota?

HALL

There wasn’t anything I would call a group. I did get out to the Blys’ a couple of times. The summer of 1961 I was there for two weeks along with the Simpsons. Jim Wright came out from Minneapolis for the two weekends. We four males spent hours together looking at each other’s poetry. Of course we had some notions in common and we learned from each other, so maybe we were a group. I remember how one poem of mine got changed then, “In the Kitchen of the Old House.” I’d been fiddling with it for two years. It began with an imagined dream—which just didn’t go—and I said in frustration something like, I remember when this started. I was sitting in the kitchen of this old house late at night, thinking about . . . Three voices interrupted me: Write it down! Write it down! This poem needed a way in.

We worked together and we played competitive games like badminton and swimming, but poetry was the most competitive game. We were friendly and fought like hell. Louis was the best swimmer and Robert always won the foolhardiness prize. There was a big town swimming pool in Madison where we went every day, and Robert would climb to the highest diving platform and jump off, making faces and noises and gyrating his body all the way down. I won at badminton.

Robert and I—he was Bob then and I feel stiff saying Robert—met at Harvard in February of 1948 when I tried out for the Advocate. He had joined the previous fall when he first got to Harvard, but I waited until my second term. After school was out that summer, he came down to Connecticut and stayed at my house for a day or two. I was nervous having my poet friend there, afraid of confrontation between Robert and my father. At lunch Robert said, Well, Mr. Hall, what do you think of having a poet for a son? As I feared, my father didn’t know what to say; poetry was embarrassing, somehow. So I said, Too bad your father doesn’t have the same problem, and my father laughed and laughed, off the hook.

Robert and I have written thousands of letters back and forth, and we’ve visited whenever we could. You know these people who hate Robert and write about how clever he has been at his literary politicking? They don’t know anything about it. For years and years he was a solitary. I remember a time before I moved to Ann Arbor when Robert came back from Norway and stopped to visit while I lived outside Boston. He was talking about going back to the Madison farm and starting a magazine. He had discovered modernism in Norway and wanted to tell everybody—but also he wanted to remain independent. Knowing literary people would only make it harder for him, so he did not want to know anybody besides me. Then he said, I don’t want to know James Wright. How can I write about James Wright if I know James Wright? He wasn’t being nasty about Jim; he brought up Jim’s name because Jim had just taken a job at the University of Minnesota—three or four hours away from Madison. They didn’t get to know each other until a couple of years later when Jim wrote him an anguished letter. Jim read Robert’s attacks on fifties poetry in The Fifties and decided that everything Robert said was right and everything Jim was doing was wrong. Jim was always deciding that he was wrong.

Robert wanted solitude and independence. He was going to lecture everybody, as he always has done and still does, but from a distance. If he wanted eminence, he wanted a lonely eminence. He came out of his isolation, I think, at that conference in Texas when he took the floor away from the professors. Do you know about that?

INTERVIEWER

No. This is something I haven’t heard about.

HALL

It was a moment. The National Council of Teachers of English invited young poets, as they called us, to a conference in Houston in 1966. They brought Robert Graves over to lecture, and they brought in Richard Eberhart, calling him dean of the younger poets. Dick was fifty-two; that made him dean. Most of the young poets were forty or close to it. There was W. S. Merwin, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, Gary Snyder, Carolyn Kizer, Robert, I . . . And also: Reed Whittemore, Josephine Miles, William Stafford, May Swenson. Young poets! Several of us flew down from Chicago together. We stood in the aisle of a 707 singing “Yellow Submarine”—Bly, Snyder, Creeley, and I. We stayed up all night in somebody’s room at the Houston hotel talking about poetry. Creeley had an over-the-shoulder cassette recorder and every time Duncan spoke he turned it on and every time Duncan finished speaking he turned it off. We stayed up until six in the morning and Eberhart’s talk was at eight-thirty, so we didn’t get a whole lot of sleep.

We met in a huge hall filled with thousands of English teachers. Eberhart talked about how the Peace Corps sent him to Africa; he observed a tribe of primitive people and told us that civilization lacked spontaneity. Dick discovers Rousseau! Someone else got up, a respondent, and said something silly. Then Lawrance Perrine, who edited the textbook Sound and Sense, stood up as another respondent. He talked conservatively about poetic form, saying something in praise of villanelles—in 1966!— which made it sound as if all poems were really the same, as if nothing mattered, not what you said or how you said it. I’m unfair, but all of us were tired, some of us were hung over, and everything we heard sounded fatuous after the energizing talk of the night before. So Robert stood up in the front row—turning around to face these thousands of people, interrupting the program—and said: He’s wrong. We care about poetry. Poetry matters and one thing is better than something else . . . He went on; I can’t remember . . . Whatever Bly said, it was passionate. It woke everybody up, I’ll tell you. Thousands of teachers applauded mightily. As Robert sat down and the program was about to proceed, somebody in the audience said, Let’s hear from all the poets. So we took over, to hell with the program, and one by one each of us read a poem and talked. It was Vietnam time and a lot of us talked about politics. Robert gave the rest of us courage, and his platform life began at that moment: he found his public antinomian presence.

INTERVIEWER

Somehow one doesn’t think of Robert Bly as having graduated from Harvard—but there were many poets there at the time, weren’t there?

HALL

Robert went one year to St. Olaf in Minnesota and then transferred to Harvard. He and I overlapped for three years, becoming closest friends, always opposites. The two of us are Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. On the Advocate with us were Kenneth Koch and John Ashbery. Frank O’Hara was never on the Advocate, but he was a member of the first class I took in writing, taught by John Ciardi, who was a wonderful teacher. I remember John coming into class one day and saying something like, I just sold eight poems to The New Yorker, I bought my first car, and next election, I’ll probably vote Republican. John supported Henry Wallace in 1948, very progressive. Be wary of what you joke about. O’Hara was writing poems then, but I didn’t know it; I saw his short stories. Frank gave the best parties at Harvard: incongruous, outrageous bunches of people. I remember Maurice Bowra, visiting from Oxford, as he bounced and burbled on Frank’s sofa. Frank was in Eliot House, as I was, and his roommate was the artist Ted Gorey—Edward St. John Gorey. Frank was the funniest man I ever met, utterly quick-witted and sharp with his sarcasm. Once, in his presence, I made some sort of joshing reference, comparing him to Oscar Wilde. Being gay was relatively open, even light, in the Harvard of those years. One of Frank’s givens was that everybody was gay, either in or out of the closet. He answered me with a swoop of emphasis: You’re the type that would sue.

I admired Ashbery; we all admired John, although in general we were not a mutual admiration society. In general we were murderous. John was at that time reticent, shy, precocious. He had published in Poetry while he was still at Deerfield Academy. On the Advocate, we were terribly serious about the poems we published. We would stay up until two or three in the morning arguing about whether a poem was good enough to be in the magazine. One time we had a half-page gap and asked John to come up with a poem. After some prodding, he conceded that maybe he had a poem. He went back to his room to get it, and it took him forty minutes. We didn’t know it then, but of course—he later admitted—he went home and wrote the poem. In 1989 I told John this story—wondering if he remembered it as I did—and he even remembered the poem, which began, Fortunate Alphonse, the shy homosexual . . . He told me, with a sigh, Yes, I took longer then.

One night Bly came back from a dance at Radcliffe saying he had met a girl from Baltimore, a doctor’s daughter who knew all about modern poetry. Adrienne Rich! I met her and we dated, though we didn’t get to know each other until a couple of years later. She published her first book, which Auden chose for the Yale Series of Younger Poets, when we were seniors. My second year at Oxford, she won a Guggenheim (at the age of twenty-two) and chose to spend her time in Oxford—not studying, just in town. That’s when we became friends, and for several years we worked closely together. In 1954 and 1955 Adrienne and I were back in Cambridge at the same time. I baby-sat every morning while my wife went back to school, and one day a week Adrienne, pregnant with her first child, dropped by from eight in the morning until one o’clock. We talked poetry while I fed and bathed my son Andrew. Many years later, Adrienne and I were talking about those times—early marriages and casserole cookery—and we talked about the sex roles we played. Don, Adrienne told me, you taught me how to bathe a baby.

At Harvard, I also knew Peter Davison, L. E. Sissman, Kenward Elmslie. Bob Creeley left the term before I arrived. He was chicken farming in New Hampshire, but I met him and talked poetry with him at the Grolier Book Shop where you met everybody. Creeley and I got along famously, but a couple of years later I insulted him in a magazine piece and we were enemies for a while. A little while ago, Bob sent me a book that included a stick-figure account of his life and he put a check mark by one item: he had quit a publishing venture, on Majorca with Martin Seymour-Smith, because Seymour-Smith wanted to print my poems.

Richard Wilbur was older—he was born in 1921 and at that time seven years difference was something. While I was an undergraduate, he was a junior fellow, with a young family at home, so he had a room at Adams House to work in. He was such a generous man. I brought him poems to look at and he showed me what he was up to. I remember him working on Ceremony. Archibald MacLeish came to Harvard as Boylston Professor when I was a junior. Dick Eberhart lived in Cambridge. Frost lived there fall and spring, and when I was a junior fellow Robert Lowell came to Boston. Quite a bunch.

INTERVIEWER

Did you know Lowell?

HALL

A little. Lord Weary’s Castle was my favorite book of the time—which it still is—and I loved “Mother Marie Therese” and “Falling Asleep Over the Aeneid” from the next book. When the Life Studies poems started in magazines, a little later, it was totally shocking, but some were great. I can’t remember how we met. He and Elizabeth Hardwick came to dinner and we went to their place. There was a bunch that met for a workshop a few times at John Holmes’s house—Phil Booth and Lowell and me with Holmes. Lowell was gentle and soft-spoken—I never saw him when he was in trouble—but candid. These get-togethers were fine, but they never flew. Maybe I was too much in awe. For a while Lowell wrote me some of those postcards he was famous for. He wrote about an essay I did in which I said that every time I learned to make a new noise in poetry I found something new to say. He said he’d heard me say the same thing at a Harvard reading and that it helped him toward Life Studies. A few years later, out in Ann Arbor, he came to my house and we spent an evening together drinking and reading poems out loud. He read me most of Near the Ocean. I was surprised by how much he wanted my approval—but of course, like anybody, he wanted everybody’s. Then when he started doing self-imitations with the Notebook stuff, I was disappointed. Hell, I was furious—he let me down, as it were—and I attacked him in print. He quoted from one of my attacks in one of those little sonnets—and he rewrote my words a little, so that they sounded more pompous—but he didn’t say whom he quoted. We never saw each other after that.

INTERVIEWER

After your time at Oxford, you spent a year at Stanford studying with Yvor Winters, whose name is not generally associated with yours. What came out of that experience?

HALL

I learned more about poetry in a year, working with Winters, than I did in the rest of my education. Also, I was fond of him—we even stayed in his house during Christmas vacation while he went off to visit relatives—but one incident in the spring gave me pause. At a party at his house, he said to me, Would you get some more ice, son? When he called me son it was as if he breathed in my ear; I’d follow him anywhere. I thought, It’s good I’m getting out of here.

When I went to Stanford I had already spent years working in a conservative poetic. In those days, most of us worked in a rhymed iambic line. I did it—James Wright, Louis Simpson, Galway Kinnell, Adrienne Rich, Robert Bly, W. D. Snodgrass, W. S. Merwin. When I applied for the fellowship, my work didn’t depart greatly from the structure and metrics that Winters advocated. He thought I had some technical competence or I wouldn’t have had the fellowship. The best poem I wrote at Stanford was “My Son My Executioner,” which could almost have come out of the seventeenth century—the abstract diction, the way it looks reasonable treating the irrational. For that one year I became briefly more conservative than ever, and it became known that I was the poetry editor for The Paris Review. Some old acquaintances sent me poems, including Frank O’Hara. Frank hadn’t discovered himself, quite, but he wasn’t writing rhymed iambic pentameter either. I rejected his poems and wrote a supercilious note. Stupid! Not long ago I came across Frank’s answer in which he accused me of writing second-rate Yeats, which was perfectly true. The letter is snippy, funny, outraged, but cool.

I regret I didn’t have the brains to take his poems, but I couldn’t read them then. I did do early work by Hill, Gunn, Bly, Dickey, Wright, Rich, Merwin . . . lots of people. But also I rejected a good poem by Allen Ginsberg, who wrote George Plimpton saying that I wouldn’t recognize a poem if it buggered me in broad daylight.

INTERVIEWER

Back to the way you write. Has it changed over the years?

HALL

When I was younger, poems arrived in a rush, maybe six or eight new things begun in two days, four days. I’d be in a crazy mood, inspired; I’d walk into furniture and not recognize my children. After the initial bursts, I would have my task set out before me—to bring out what was best, to get rid of the bad stuff, to work them over until I was pleased or satisfied. Then for nine years or so—late thirties into forties—I was unable to write anything that was up to what I’d done earlier. I thought I’d lost it. After all, if you read biography, you know—people lose it. Then in the autumn of 1974 I started Kicking the Leaves and most people think that’s when I finally got started as a poet. I was forty-six.

With these new poems, I began to follow a different process of composition, one I’ve stuck with ever since. Usually now I begin with a loose association of images, a scene, and a sense that somewhere in this material is something I don’t yet understand that wants to become a poem. I write out first drafts in prosaic language—flat, no excitement. Then very slowly, over hundreds of drafts, I begin to discover and exploit connections—between words, between images. Looking at the poem on the five-hundredth day, I will take out one word and put in another. Three days later I will discover that the new word connects with another word that joined the manuscript a year back.

Now inspiration doesn’t come at once, several poems starting in a few days; it comes in the discovery of a single word after three years of work. This process never stops. When a new book of mine arrives in the mail, I dread reading it—because I know I will find words I want to change. I revise when I read my poems out loud to an audience. I change them when they appear in magazines or anthologies. I can’t keep my hands off poems. I wrote “The Man in the Dead Machine” in 1965, published it in 1966, and I read it aloud a thousand times. Then in April of 1984, driving to the Scranton airport after a reading, I saw how to make it better. So I did.

The kind of poem I’ve taken to writing is something you could call the discursive ode. I call it an ode because although it’s lyrical it tries for a certain length and inclusiveness. I call it discursive because it appears to wander, to move from one particular to another by association, though if it succeeds it finds a unity. It tries to connect things difficult to connect, things that at first seem diverse; often the images make a structural glue. I suppose it’s largely a romantic form but one can find classical sources for it, in the satires, maybe in some of Horace’s odes, maybe even in neoclassic poems by Johnson and Pope. But it flowers in the ode, even in something as short as the “Ode to a Nightingale” or later “Among School Children.”

INTERVIEWER

You seemed with Kicking the Leaves to enter a third phase of your career. Somewhere in an essay or interview I believe you described the first two phases. In the first, you wrote a poetry of the top of the mind, where consciousness was very much in control. In the second phase, you reversed that, letting the unconscious mind rule, letting all sorts of unexpected and unsettling things into the poem. Now in the third phase it may be that you are combining the two.

HALL

That’s a goal. Even when I was in the second phase, dredging things from the dark places, I wanted to bring them into the light. Freud said, “Where Id was, there Ego shall be.” I wanted to subject things—even subterranean things—to the light of consciousness. During the first phase, I had a dream of conscious control, libido sciendi; unconscious materials only occurred when I hid them from myself, as in “The Sleeping Giant,” where I wrote an Oedipal poem without any idea of what I was doing. Today when I begin writing I’m aware: something that I don’t understand drives this engine. Why do I pick this scene or image? Within the action of kicking the leaves something was weighted, freighted, heavy with feeling—and because I kept writing, kept going back to the poem, eventually the under-feeling that unified the detail came forward in the poem. The process is discovering by revision, uncovering by persistence.

INTERVIEWER

Was your recent long poem, The One Day, written in this way?

HALL

This material started to arrive during my years of flailing about. It came in great volcanic eruptions of language. I couldn’t drive to the supermarket without taking a notepad with me. I kept accumulating fragments without reading them or rewriting; it was as if I was finding the stone that I would eventually carve sculpture from. Then when it stopped coming, I went back and read it. It was chaotic, full of inadequate language—and it was also scary. There was spooky stuff out of childhood; there was denunciation and mockery that years later went into “Prophecy” and “Pastoral.” Something let me loose into this material, something that I was scared to revisit. So I let it rest, waiting until the lava cooled down and hardened. That took years. Finally in 1979 or 1980 I took a deep breath and began to try to make it into poetry. And I added new material; half of the poem—or more—came during the later writing. There were false starts; at one point, maybe in 1982, I had a long asymmetric free-verse poem in thirty or forty sections, each several pages long and with its own title. No good. Later I discovered the ten-line blocks that I could build with. I could keep them discrete or I could bridge from one to the next.

INTERVIEWER

When you describe your process of discovery in conversation you seem almost to be describing the process of free association that a psychoanalyst asks for. Is this parallel valid?

HALL

It’s no accident. I spent seven years in therapy, up to three times a week, with a Freudian analyst. He was an old man with a light Austrian accent and athletic eyebrows; I would explain carefully and reasonably why I had done something cruel or stupid; his eyebrows would do the high jump. We fell into the habit of treating poems as dreams. When you bring a dream to a therapist or analyst, he or she isn’t likely to pay attention to the manifest content, but if you have a table in that dream he may ask, What does the table look like? The table might be the key to what the dream—or the poem—is actually about. In “The Alligator Bride” there’s an Empire table. Freudian analysis is a word cure, and it resembles the way we read or write poems. Poems that I wrote in my frenzy were like dreams because they allowed something unconscious to loosen forth. Those years allowed me to overcome fears of hidden things and let them out. Coming into my doctor’s office, I learned how to tap instantly into the on-flowing current inside my head. That essential step took me about a year, but once you learn it you don’t lose it. I learned to listen for the vatic voice, to watch images running over the mindscreen, to give a telegraphic account of what I heard and saw. It was good for me as a creature and good for me as a poet. Even now I talk with my doctor every day of my life and he explains the sources of feeling—although he’s dead. Eventually it was psychotherapy that allowed me to recover my life. And to write The One Day.

INTERVIEWER

So there is a sense in which you are touching a deeper Donald Hall in this material.

HALL

I hope so, yes. Not in any boring autobiographical way. In The Happy Man I have a poem in which somebody talks about his time in the detox center. A friend asked me what I was in detox for. Well, I never was. For the poem I made up a character; I talked through a mask I invented, which I do all the time. I love to fool people, even with fake epigraphs—but also I wish they weren’t fooled. Of course my poems use things that have happened to me, but they go beyond the facts. Even when I write about my grandfather, I lie. I don’t believe poets when they say I, and I wish people wouldn’t believe me. Poetic material starts by being personal but the deeper we go inside the more we become everybody.

INTERVIEWER

Has the passage of time, the coming of age if you will, caused any other changes in your notions about your poetry, your career as a poet?

HALL

I’m more patient now. When I was in my twenties, I wanted to write many poems. I had goals; when I reached them, they turned out to be not worth reaching. When you begin, you think that if you could just publish a few poems, you’d reach your desire; then if you could publish in a good magazine; then if you could publish a book; then . . . When you’ve done these things you haven’t done anything. The desire must be, not to write another dozen poems, but to write something as good as the poems that originally brought you to love the art. It’s the only sensible reason for writing poems. You’ve got to keep your eye on what you care about: to write a poem that stands up with Walt Whitman or Andrew Marvell.

Another thing that’s changed is my sense of daily time. I spent years of my life daydreaming about a future, I suppose in order to avoid a present that was painful. Teaching in Ann Arbor I daydreamed about a year in England. Mentally I lived always a step ahead of myself, so that the day I lived in was something to get through on the way to something else. Pitiful! After I left teaching, when Jane and I had lived at Eagle Pond for a year, I realized: I’m aware of the hour I live in; I’m not daydreaming ahead to a future time; I know which direction the wind blows from and where the sun is; I’m alive in the present moment, in what I do now, and in where I’m doing it. This present includes layers of the past—there’s so much past here at Eagle Pond—but it doesn’t depend on a daydream future that may never arrive.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve always written a lot about Eagle Pond, things like how your grandmother used to stand at that kitchen window in the morning and check the mountain. Well, it’s the same window today and the same mountain. The profound presence of the past in a place like this, even the felt presence of those who have lived here but are now dead, the cows and other animals in your poems—does all this have anything to do with the general elegiac cast to your poetry?

HALL

My grandmother’s father, who was born in 1826 and who died fifteen years before I was born, looked out that same window to check that same mountain. I stand in the footprints of people long gone—which I find an inspiriting connection; it belittles the notion of one’s own death; it says, That’s all right. Everybody who has looked at this mountain has died or will die. Then others will look at it. A sense of continuity makes for an elegiac poetry. One of my first published poems, when I was sixteen, was about a New Hampshire graveyard. When we were at Harvard, Robert Bly used to call me the cellar-hole poet—like a graveyard poet in the eighteenth century. When I spent my childhood summers here among the old people, absence was everywhere. Walking in the woods I found cellar holes, old wells, old walls. Even now you can sometimes feel under your feet in dense woods the ruts that plows made long ago.

INTERVIEWER

As you talk about this, I hear almost a sacred sense of place. You have written about attending church here as primarily a social experience—but you are also a deacon and I am wondering about the more serious implications of this activity.

HALL

It began from a social feeling, but moved on—from community to communion. When I was a child I went to church every Sunday simply because that was what we did. Uncle Luther, my grandmother’s older brother, who grew up in this house, was our preacher. He’d retired from a Connecticut parish and at eighty delivered lucid fifteen-minute sermons without a note in front of him. He was born in 1856 and could remember the Civil War. I used to sit on the porch and get him to tell me stories about the Civil War.

I enjoyed church as a child—sitting beside my grandfather, all dressed up, who fed me Canada mints. But I can’t say that I was taken with Christian thought or theology. When I was about twelve I had the atheist experience. I suddenly realized, with absolute clarity, that there was no God. With this knowledge, I felt superior to other people. Twenty years later when I was living in an English village called Thaxted I fell into the habit of attending church every Sunday—I thought without religious feeling; I loved the ceremony and the wonderful old communist vicar, Jack Putterill. His church used a preprayer book service that was so high only dogs could hear it, and his sermon, after incense and holy water, was a fifteen-minute communist homily. I thought I attended these services out of aesthetic and social motives; now I suspect that I harbored religious feelings I feared to acknowledge.

In Ann Arbor I never went to church. When Jane and I moved back here, I must have been ready. On that first Sunday, I thought, They will expect us to go to church. We decided to go just that once. In the middle of his sermon our minister quoted Rilke. I’d never heard Rilke quoted in the South Danbury Church! We were already fond of the people—mostly cousins—and we went back next Sunday, and the next. Slowly, we started reading the Gospels and some Christian thought—like “The Cloud of Unknowing,” Meister Eckhart, Julian of Norwich. At one point that winter Jane was sick and couldn’t go. I said, I’ll stay home with you. Five minutes before church, I said, I can’t stand it, and off I went. These feelings amazed me . . . and they were accompanied by thoughts; our minister ranged all over the place in his sermons. He loved Dietrich Bonhoffer, the German Protestant theologian who plotted against Hitler and was executed, a modern saint and martyr.

By this time, I would like to call myself a Christian, though I feel shy about it. We have many visitors whom Christianity makes nervous; they seem embarrassed for us. So many people expend their spirituality piecemeal on old superstitions like astrology that they entertain but don’t believe in—like the imperial Romans and their gods. I dislike contemporary polytheism, that nervous searching that provides itself with so many alternatives that it doesn’t stick itself with belief: the God of the Month Club.

The minister who loved Bonhoffer and mentioned Rilke was Jack Jensen, who died of cancer in 1990. We feel terrible grief over him. He taught at Colby-Sawyer College nearby, and had a divinity degree from Yale as well as a Ph.D. in philosophy from Boston University, a man of spirit and brains together. Watching him, listening to him, I became aware that it was possible to be a Christian although subject to skepticism and spiritual dryness. I used to think that Christians believed everything, and all the time, which is nonsense. If you have no dry spells, I doubt your spirit. We watched Jack live through the deserts when he would give sermons that were historical or philosophical. After a while he would liven up, go spiritually green again. He was a great one for Advent, the annual birth or rebirth of everything possible. Although the history of the church is often horrible—I always think of Servetus, the Spanish humanist condemned to the stake by the Italian inquisition, who escaped to Zurich, where Calvin’s people burned him—still, there’s power in two thousand years of worship and ritual coded into our Sundays. In China we went to an Easter service and heard the choir belt out “Up From the Grave He Arose” in Chinese. So much culture and geography collapses into the figure of Christ. That’s what remains, after all, at the bottom of the two thousand years—this extraordinary figure in Palestine, the figure of Christ.

INTERVIEWER

I haven’t asked you about Jane Kenyon. There are after all two poets of Eagle Pond Farm.

HALL

I know. Everything that my life has come to—coming here, the church, my poems of the last fifteen years—derives from my marriage to Jane in 1972. And I’ve watched her grow into a poet. Amazing. Of course we work together; show each other what we’re doing; occasionally getting a little huffy with each other, but helping each other all the same. But it’s living with her that’s made all the difference for me. We have the church together as well as the poetry and baseball. But I don’t want to go on about it. I don’t want to sound like someone making an acknowledgement in a book. Some day she’ll do her own Paris Review interview.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s end with one more historical question. Since we are talking just now on the stage at the Y in New York City, I wonder if you would tell me the story of the first reading you gave here.

HALL

I think it was in 1956, thirty-four years ago, that I read here for the first time. I was on a program with May Swenson and Alastair Reid and I read third. In those days, instead of all three of us sitting out here and listening to each other, we waited in the green room until it was our turn. I was nervous. This reading might have been my second or third ever, certainly my first in New York City—and this was the Y. I nipped at the scotch that Betty Kray provided in the green room. Then I thought about where I was and I nipped some more. When I came out here to read, I was still able to see the pages of my book, and I didn’t fall down, but I was horrible. I was at a stage of drunkenness that allowed me to think that I was George Sanders. I felt wonderful sophistication and coolness, sure that everything I said was utterly witty and wonderful. I was a horse’s ass.

Author photograph by Nancy Crampton.