Issue 120, Fall 1991

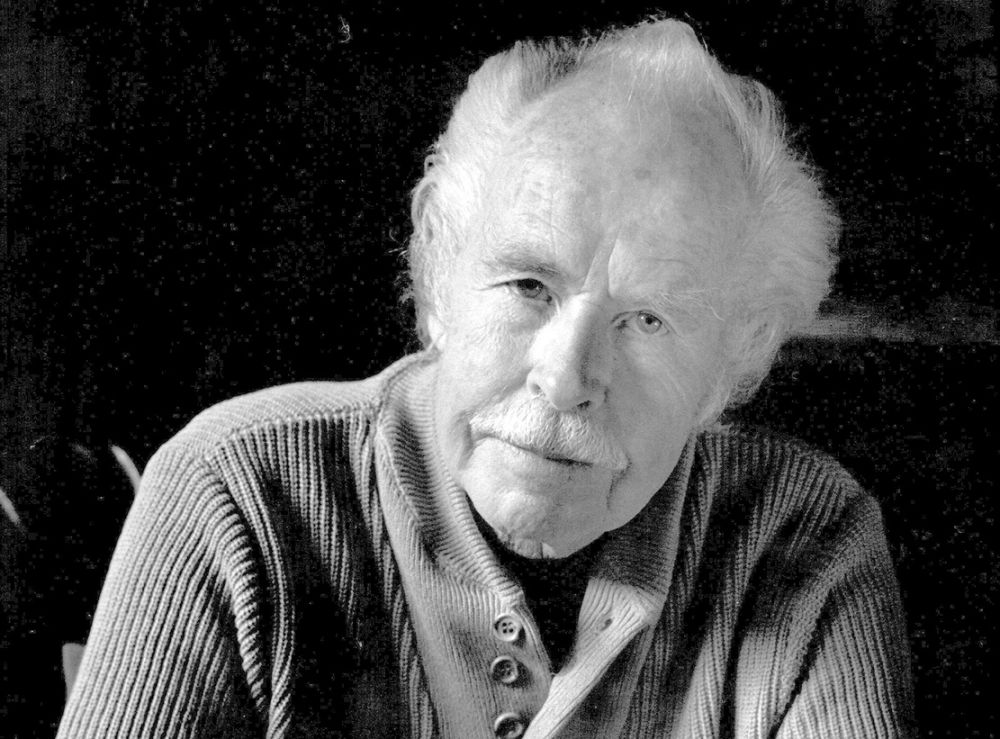

Wright Morris was born in Central City, Nebraska, in 1910 and spent his first ten years in that area. He moved to Chicago in the twenties and then attended Pomona College in California. After a year traveling in Europe in 1933, he settled on the West Coast and began writing and taking photographs. Morris is the author of nineteen novels, including Love among the Cannibals (1957) and Fire Sermon (1971), as well as four books of essays and three volumes of memoirs: Will’s Boy: A Memoir (1980), which details his childhood years; Solo: An American Dreamer in Europe, about his time spent abroad; and finally Cloak of Light(1985) which deals with his adult life. He has been a Guggenheim Fellow and has been awarded grants from the Rockefeller Foundation and the National Institute of Arts and Letters. In 1956 he won the National Book Award for The Field of Vision. More recently Morris received the American Book Award for Plains Song (1980). His short stories have been cited by the O. Henry Awards and are regularly included in the Best American Short Stories anthologies.

Morris is also a photographer, and his own stark photographs punctuate the prose in such books as The Inhabitants (1946), The Home Place (1948), God’s Country and My People(1968), and Photographs and Words (1982). “We make to ourselves pictures of facts. The picture is a model of reality”—Morris often uses these words of the philosopher and logician Ludwig Wittgenstein to describe his own creative process. The pictures in his “photo-texts” are based on the details and artifacts of daily life in the small Nebraska towns of the Great Plains where Morris was raised.

Morris lives with his wife Josephine in Mill Valley, California, in a small contemporary wooden house tucked into a steep hillside, amidst a profusion of climbing ivy. The house, with its wide balcony, is sheltered by fragrant laurel trees and feels isolated although it is located in the center of Marin County, an area affected by relentless urban growth. Even as the interviewers drove out of San Francisco and across the Golden Gate Bridge, they passed shopping malls where gardens had flourished only last year. The Morrises’ immediate neighborhood remains untouched, however, and during the interview birds sang peacefully among the wild forget-me-nots on a bank near their home.

Inside, the house is plain and comfortable. Bookshelves line the living room, where there are deep sofas and piles of newly published art books and magazines. Several photographs by Morris hang on the walls: stark, beautiful images of the plains, the people who once populated them, and the objects they used. Morris also collects prints by the Abstract Expressionists, and a black-and-white Gorky hangs over the mantel. An outsized television set stands to the left of the fieldstone fireplace, near an audio system that brings Bach or Vivaldi into the room with an eerie fidelity. Bright striped fabrics and other mementos of Morris’s trips to Mexico are scattered about the living room. One of his books lies on the coffee table: Love Affair: A Venetian Journal. It is the only one of his photo-texts that does not specifically document the American Midwest, as well as the only one with color photographs.

Wright Morris sat in his favorite vintage Eames chair as he spoke. When the light turned golden at the end of the interview, Jo Morris brought in a tray of tea and cookies and a perfect apple pie.

INTERVIEWER

To this day your fiction is considered experimental. Critics have never had an easy time fitting you into any particular group or movement. How do you see yourself? Do you consider yourself a storyteller?

WRIGHT MORRIS

I can tell a story and often do, but it has never occurred to me to “plot” one. If I’d taken writing courses, as is done today, someone would surely have instructed me in plotting, but I discovered that a narrative could be sustained without plotting, and I have held to that practice.

INTERVIEWER

Since you don’t plot, what is it that carries you forward in the narrative?

MORRIS

Let me illustrate: my story, “Victrola,” is about an old man and a dog he has inherited from a neighbor. They tolerate—but do not like—each other. The man is ill at ease with the dog’s appearance, which he finds prehistoric, the head skull-like, the eyes too small, etcetera. There is a standoff when they look at each other. Predictably, they will have a confrontation. The origin of this is that one day I had seen this creature at the foot of the driveway. His odd appearance disturbed me. His tail did not wag. His short white pelt had been worn through on the high spots. As I approached he turned and slunk away. Not seeing him again, I often thought about him. In my story the character Bundy inherits the dog from his neighbor. They are never at ease with each other. Their daily walk is an ordeal for them both. This walk takes place in Mill Valley, where I live, and follows a prescribed route to the village park. Along this route I am scrupulous about details, but all that takes place on the walk is fiction. This commingling of a real place and imagined events provides the framework for my fiction. There is a narrative line but no plot. I accept what happens (what occurs to me) and imagine an appropriate resolution.

INTERVIEWER

What about “voice” in this setup?

MORRIS

The voice of the narrator—the narration—is crucial. If it is right, the narrative seems effortless, with one incident following another, in the manner of letting out a kite’s string. I think I came by this manner, this confidence, in the absence of the old-style linear narration—the time that flowed like a river from the past into the future. That is not the way I comprehended time. My time is cyclical—abstract, yet keenly felt. It seems appropriate to the modern consciousness. Fictive moments contain both the past and the future. Joyce captured this complexity in Ulysses. My style of plotless narration is one way of appropriating time to my purposes. All reasonably fully conscious people do this. We have no access to the old time, so we make do with our privately spun new times. I feel a faintly physical vertigo when I hear of jets that fly faster than sun-time—or in the opposing direction. It ain’t natural.

INTERVIEWER

Were you aware of what other writers were doing when you started?

MORRIS

I was slow to read my contemporaries, being too busy writing. I read schoolbooks in grade school; in high school, a book that enthralled me was Literature and Life. It began with stories from Beowulf and the adventures of King Arthur’s knights. Books were not part of my home environment. I read A Boy’s Life and the Tom Swift series. This absence of books, of what we think of as culture, spared me of having a fix on certain writers, which the young reader is prone to do.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think this contributed to developing your own voice and style of narration?

MORRIS

It left me free from the influence of familiar romances, but encouraged me to take an active part in the vernacular for which I showed some early talent. I was a talker, and took part in class productions of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer. That my style is profoundly oral I may owe to this circumstance. The sound is crucial. It frequently leads me to take considerable liberties with the syntax. As Yeats said, “As I altered my syntax, I altered my intellect.”

INTERVIEWER

When did you make the decision to be a writer? You took a trip to Europe when you were twenty-three. Did you go there to experience Europe as a writer?

MORRIS

In my third year of college I read Richard Halliburton’s The Royal Road to Romance. It inflamed my desire for adventure. The notion of becoming a writer had been planted, but had not crystallized. In the spring I was in Paris. I sometimes played Ping-Pong at the American Club with a young man from Boston. One day he asked me what it was I was writing. Well, what was I writing! I gave it a moment’s thought. He went on to say he had connections at The Atlantic, in case I had something to submit. Trifling incidents like this can crystallize budding sentiments.

INTERVIEWER

Had you written much at the time?

MORRIS

Not a thing! At that time, however, I was reading a novel by Montherlant, Les Celibataires, and I identified with the two aging bachelors. Being moved in this way was new to me. I felt a longing to create lifelike characters myself. This latter impression so reinforced the first that I was nudged from the haze of sentiment to actually think of myself as a writer. What was I about to write? Well, let me think!