Issue 196, Spring 2011

Though I will make the trip up the elevator to Janet Malcolm’s stately town-house apartment, overlooking Gramercy Park, three times in the course of this unusual interview, the substance of our exchange will take place by e-mail, over three and a half months.

The reason for this is that Janet Malcolm is more naturally the describer than the described. It is nearly impossible to imagine the masterful interviewer chatting unguardedly into a tape recorder, and indeed she prefers not to imagine it. She has agreed to do the interview but only by e-mail: in this way she has politely refused the role of subject and reverted to the more comfortable role of writer. She will be writing her answers—and, to be honest, tinkering gently with the phrasing of some of my questions.

So the true setting of this interview is not the book-lined walls of her living room, where we sit having mint tea, but screens: Malcolm’s twenty-one-and-a-half-inch desktop Mac, with its worn white keyboard; my silver seventeen-inch MacBook, my iPad sometimes. The disadvantage of e-mail is that it seems to breed a kind of formality, but the advantage is the familiarity of being in touch with someone over time. For us, this particular style of communication had the reassuring old-fashioned quality of considered correspondence; it is like Malcolm herself—careful, thorough, a bit elusive.

Malcolm was born in Prague, in 1934, and immigrated to this country when she was five. Her family lived with relatives in Flatbush, Brooklyn, for a year while her father, a psychiatrist and neurologist, studied for his medical boards, and then moved to Yorkville, in Manhattan. Malcolm attended the High School of Music and Art, and then went to the University of Michigan, where she began writing for the school paper, The Michigan Daily, and the humor magazine, The Gargoyle, which she later edited. In the years after college she moved to Washington with her husband, Donald Malcolm, and wrote occasional book reviews for The New Republic.

She and her husband moved to New York and, in 1963, had a daughter, Anne. That same year Malcolm’s work first appeared in The New Yorker, where her husband, who died in 1975, was the off-Broadway critic. She began writing in what was then considered the woman’s sphere: annual features on Christmas shopping and children’s books, and a monthly column on design, called “About the House.”

Later, Malcolm married her editor at The New Yorker, Gardner Botsford. She began to do the dense, idiosyncratic writing she is now known for when she quit smoking in 1978: she couldn’t write without cigarettes, so she began reporting a long New Yorker fact piece, on family therapy, called “The One-Way Mirror.” She set off for Philadelphia with a tape recorder—the old-fashioned kind, with tapes, which she uses to this day—and lined Mead composition notebooks with marbleized covers. By the time she finished the long period of reporting, she found she could finally write without smoking, and she had also found her form.

Her ten provocative books, including The Journalist and the Murderer, Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession, The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, In the Freud Archives, and Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice, are simultaneously beloved, demanding, scholarly, flashy, careful, bold, highbrow, and controversial. Many people have pointed out that her writing, which is often called journalism, is in fact some other wholly original form of art, some singular admixture of reporting, biography, literary criticism, psychoanalysis, and the nineteenth-century novel—English and Russian both. In one of the more colorful episodes of her long career, she was the defendant of a libel trial, brought by one of her subjects, Jeffrey Masson, in 1984; the courts ultimately found in her favor, in 1994, but the charges shadowed her for years, and both during the trial and afterward the journalistic community was not as supportive as one might have thought it would be.

In part this might be because Malcolm had already distanced herself from them. “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible,” she wrote in the now-famous opening lines of The Journalist and the Murderer, and in much of her writing Malcolm delves into what she calls the “moral problem” of journalism. One of the most challenging or controversial elements of her work is her persistent and mesmerizing analysis of the relationship between the writer and her subject. (“Writing cannot be done in a state of desirelessness,” she writes in The Silent Woman; and she exposes, over and over, the writer’s prejudices and flaws, including her own.) When The Journalist and the Murderercame out in 1990, it created a stir in the literary world; it antagonized, in other words, precisely those people it was meant to antagonize. But it is now taught to nearly every undergraduate studying journalism, and Malcolm’s fiery comment on the relationship between the journalist and her subject has been assimilated so completely into the larger culture that it has become a truism. Malcolm’s work, then, occupies that strange glittering territory between controversy and the establishment: she is both a grande dame of journalism, and still, somehow, its enfant terrible.

Malcolm is admired for the fierceness of her satire, for the elegance of her writing, for the innovations of her form. She writes, in “A Girl of the Zeitgeist,” an essay about the New York art world, "Perhaps even stronger than the room’s aura of commanding originality is its sense of absences, its evocation of all the things that have been excluded, have been found wanting, have failed to capture the interest of Rosalind Krauss—which are most of the things in the world, the things of ‘good taste’ and fashion and consumerism, the things we see in stores and in one another’s houses. No one can leave this loft without feeling a little rebuked: one’s own house suddenly seems cluttered, inchoate, banal."

No living writer has narrated the drama of turning the messy and meaningless world into words as brilliantly, precisely, and analytically as Janet Malcolm. Whether she is writing about biography or a trial or psychoanalysis or Gertrude Stein, her story is the construction of the story, and her influence is so vast that much of the writing world has begun to think in the charged, analytic terms of a Janet Malcolm passage. She takes apart the official line, the accepted story, the court transcript like a mechanic takes apart a car engine, and shows us how it works; she narrates how the stories we tell ourselves are made from the vanities and jealousies and weaknesses of their players. This is her obsession, and no one can do it on her level.

Personally, though, she exhibits none of the flamboyance of her prose. Over the course of the interview, Malcolm appears to lack entirely the writer’s natural exhibitionism, the writer’s desire to talk endlessly about herself. If at all possible she will elegantly deflect the conversation away from her journalism to journalism in general; she will often quote, elude, glide over my question, responding instead to something she is comfortable answering. She is, not at all surprisingly, the kind of person who thinks through her revelations, who crafts and shines them so that the self revealed is as graceful and polished as one of her pieces.

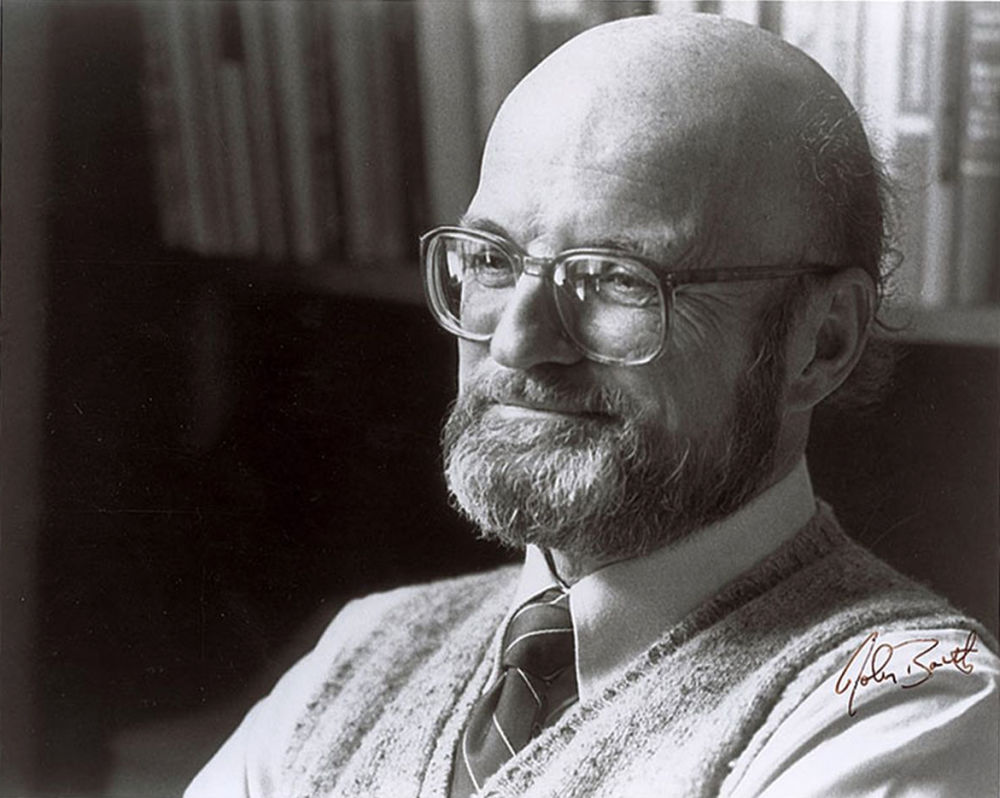

Malcolm herself is slight, with glasses and intense brown eyes, something like Harriet the Spy would look like if she had grown to the venerable age of seventy-six and the world had showered her with the success she deserved. Her ambience is controlled, restrained, watchful. You will not, no matter how hard you try, be able to measure the effect of your words on her, and you will never be able to tell, even remotely, how she is reacting to anything you say. Around her it is hard not to feel large, flashy, blowsy, theatrical, reckless. Even though I ostensibly am interviewing her, I am still nervous about what impression I am making on her, still riveted and consumed by the idea of the three penetrating sentences she could make of me should she so desire.

Later, she will write to me, "Before I try to answer your question, I want to talk about that moment in our meeting at my apartment last week, when I left the room to find a book and suggested that while I was away you might want to take notes about the living room for the descriptive opening of this interview. Earlier you had made the distinction between writers for whom the physical world is significant and writers for whom it scarcely exists, who live in the world of ideas. You are clearly one of the latter. You obediently took out a notebook, and gave me a rather stricken look, as if I had asked you to do something faintly embarrassing."

I opened the notebook and took out a pen, but I already know that a large part of what is going on in the room, between the journalist, say, and the murderer, won’t quite make it onto the page.