Issue 238, Winter 2021

Copyright © Laura Owens.

Gary Indiana was in his late thirties by the time he began to publish fiction, which may account for his wide array of sidelines. For many years he wrote and performed for theater, cabaret, and arthouse cinema. From 1985 to 1988 he savaged the pretensions of the art world each week as the critic for the Village Voice, and he is now an artist himself: one of his video pieces, Stanley Park (2013), which appeared in the 2014 Whitney Biennial, was shot in the ruins of a prison in Cuba, a country Indiana has visited since the late nineties. The piece, which inflects left-wing politics with black comedy, includes a snippet of Josef von Sternberg’s 1941 melodrama The Shanghai Gesture. In 1951, a group of surrealists riffed on scenes from that film in a game of exquisite corpse that became one of the inspirations for Indiana’s 2009 novel, The Shanghai Gesture. Indiana’s fictions take many forms—true crime, picaresque, noir, lament—but all are driven by the engine of his ruthless sensibility. His characters dash through mazes of deceit and exploitation; cruelty is a central theme.

Indiana’s first novel, Horse Crazy (1989), sets a miserable love affair in a New York wracked by AIDS, and served as a peephole into the seventies and eighties bohemia dubbed “downtown,” which Indiana was a part of and refuses to glamorize; his roman à clef Do Everything in the Dark (2003) is a fractured dirge for that milieu. The past few years have seen a kind of Indiana renaissance. Semiotext(e) has reissued his American crime trilogy, Resentment: A Comedy (1997), Three Month Fever (1999), and Depraved Indifference (2001)—each concerns a famous murder case, but ultimately is about what happens when inner agony collides with mass delusion—and has published a volume of early plays, short fiction, and poems, Last Seen Entering the Biltmore (2010), as well as Vile Days (2018), a thick book of his Voice columns. Seven Stories Press has republished Horse Crazy and Indiana’s second novel, Gone Tomorrow (1993), and will put out a collection of his essays, Fire Season, in 2022. These days he often meets young people who tell him they love his books.

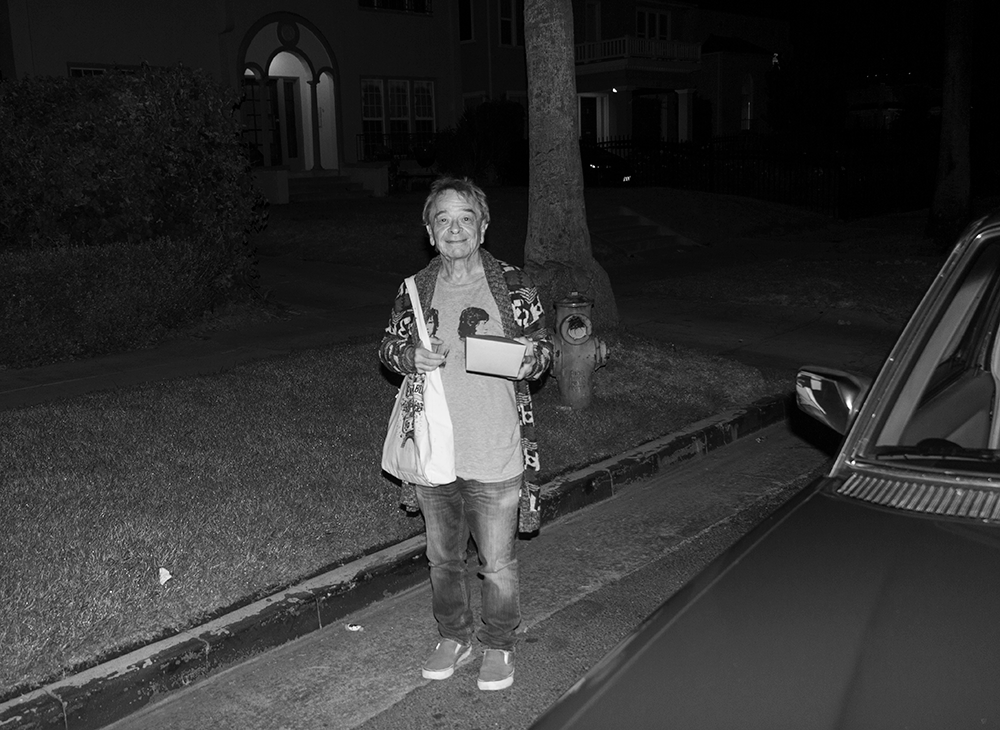

A small man, Indiana makes prodigious use of his hands and arms, slicing the air for emphasis or illustrating an idea with a twirl of the wrist. He can conduct whole conversations in a mode of rich, elaborate irony, yet he’s also insistent in his opinions and extravagant in his disdain—a mix of prince and punk. Language comes blooming out of him without prompting and without reservation, and he delivers even the most offhand joke or anecdote with wicked relish. But he did not enjoy being interviewed. I suspect that the very enterprise—the pressure, the invasiveness, the sacramental grandiosity—smacks of a gilded literary culture to which he’s vigorously opposed. During our conversations he frequently broke off to deplore the way he thought he sounded. On one occasion, he took refuge in a long telephone call with a mutual friend of ours, counseling her about her Ambien dosage.

This interview began at a bistro in Paris, where Indiana made a stop after visiting his friend the painter Laura Owens in Arles. It ended in the sixth-floor walk-up on Eleventh Street where he has lived and worked since the eighties. The basement of the building, where Patti Astor’s Fun Gallery opened in 1981, now houses a psychic. Floor-to-ceiling bookshelves dominate every wall in the apartment, except for the kitchen’s; his current reading is on a cocktail trolley by the bed. When I picked up Considerations on the Assassination of Gérard Lebovici by Guy Debord, he said he loved Debord’s “alcoholic style”; I spotted two copies of Amiri Baraka’s The System of Dante’s Hell. More books are always arriving, in packages addressed to Gary Hoisington, the name given to him when he was born, in 1950, in Derry, New Hampshire. He has had cause to regret the pseudonym he chose on a whim. “Oh, hi,” John Ashbery said when they were introduced. “I’m Lowell Massachusetts.”

INTERVIEWER

You belong to the category of writers who have also been actors, which includes Mae West and Sam Shepard. What were your strengths as an actor?

GARY INDIANA

I wasn’t trained, and I certainly didn’t have the technique of a professional. Directors would cast me because of the way I was, not what I could pretend to be. Often the wardrobe does half the work anyway. I was more of a special effect—they wanted my personality, or how I looked at the time. When I performed, I had—and this maybe had something to do with how much I drank—a quality of demonic abandon.

INTERVIEWER

In Valie Export’s The Practice of Love, you’re screaming in a bathrobe.

INDIANA

In Christoph Schlingensief’s Terror 2000, I’m also just screaming, mostly. That was one of my bigger roles. The film was based on real events that took place just after the reunification of Germany. I was a social worker helping Polish refugees get settled, and Udo Kier was the head of a gang of terrorists. They burst onto the train where I’m singing this song of welcome, and he shoots me with a machine gun.

INTERVIEWER

Were you serious about acting?

INDIANA

I liked doing it. It was fun. I got to go to Europe and hang out with a lot of really fabulous people I’d admired my whole life, like Delphine Seyrig. She and I met on the set of Ulrike Ottinger’s film The Image of Dorian Gray in the Yellow Press. I played a spy, always in a kitschy Bavarian costume.

INTERVIEWER

Rent Boy (1994) has an epigraph from Werner Schroeter, and Gone Tomorrow takes place on a film set. Some of your novels remind me of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Did your work in film affect your writing?

INDIANA

All the time I was acting I was also writing. I was always around directors—people I’d interviewed for some publication or done some writing for or whom I knew socially. I derived part of my sensibility from them, especially from Fassbinder. There was a merciless realism to his view of things. If you look at Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day, you can see that he was very energized by a vision of how society could be better arranged. People think his films are cynical, but they’re not—they depict a cynical social order that really enraged him.

I got a lot from Schroeter, too. A truly magical human being. Werner obliged me to read all three volumes of Ernst Bloch’s The Principle of Hope. He also obliged me, less productively, to rehearse The Comedy of Errors in a pre-Schlegel German translation for months. He hired a dialogue coach for me, an embittered actor who was in some detective series on TV, and he really hated me. He would preface every session by demanding, “Why is Werner Schroeter having you, an American, do this play at the Freie Volksbühne when you don’t even speak German?” I was to deliver this really long speech right when the curtain went up. I would tell Werner, “I can’t learn German, I can’t,” and he would say, “Anybody can learn German.” Finally I quit, and he was angry with me for a long time afterward. When I went back to Berlin to watch the production, he’d cut the entire speech down to three lines. I could easily have done it.