Issue 138, Spring 1996

The fifth of six children, John Gregory Dunne, the son of a prominent surgeon, was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1932. He went to school at Portsmouth Priory (now Abbey) and on graduation moved on to Princeton, graduating from there in 1954. To please his mother he applied to the Stanford Business School, but changed his mind (if not hers) and instead volunteered for the draft. He served for two years in the army as an enlisted man, his overseas service spent with a gun battery in Germany. He speaks of his years at the Priory (where the monks were “very worldly”) and in the army as being far more valuable than his time at Princeton. “In the army I was exposed to people I would not otherwise have known. I learned something about life.”

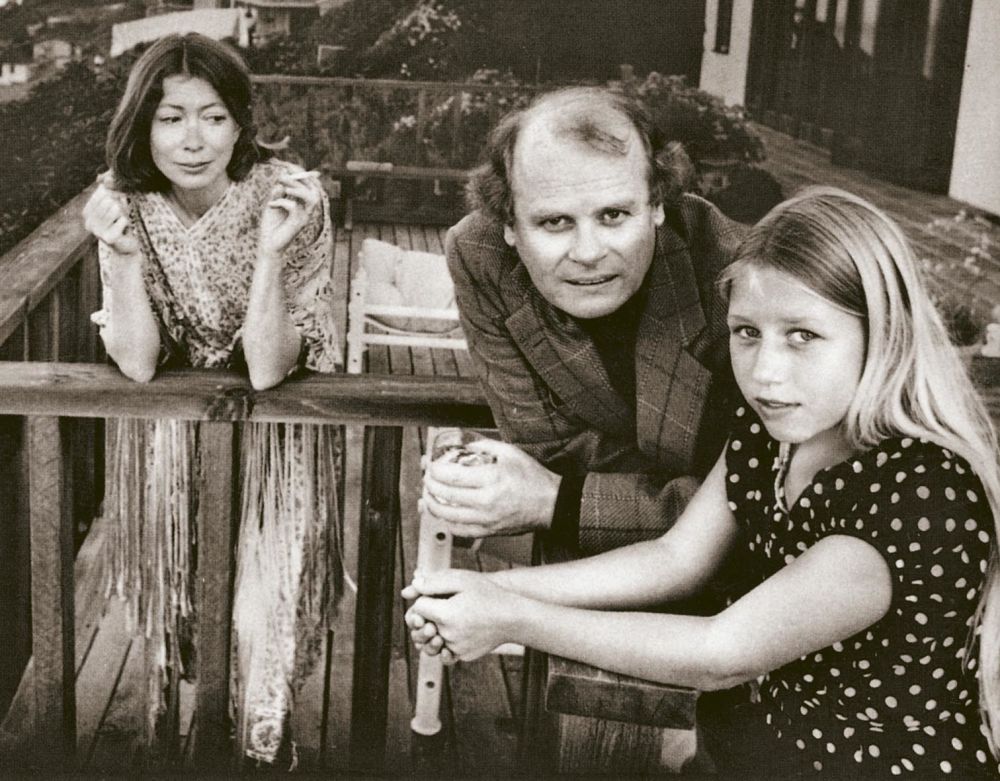

Back in the States after his service, Dunne worked briefly in an ad agency (he was fired), then with the magazine Industrial Design. In 1959 he went to Time magazine and worked there until 1964, the year he married the author Joan Didion. Since devoting himself to his own work, Dunne has written a number of novels, including The Red White and Blue, True Confessions, Dutch Shea, Jr., Vegas and Playland and two nonfiction books, Harp and The Studio. He and Didion together have written over twenty screenplays, seven of which have reached the screen: The Panic in Needle Park, Play It As It Lays, A Star Is Born, True Confessions, Hills Like White Elephants, Broken Trust, and most recently Up Close and Personal.

At present the couple lives in a large sunny apartment on New York’s Upper East Side. One is struck by how neat and ordered everything is—no sense of confusion, files in neat piles. The floors throughout the apartment are bare, polished. The considerable library is in order: the fiction titles only fill the shelves of the master bedroom.

Both have workrooms. When the pair works on a screenplay, each does a separate draft and then the two meet, sitting opposite each other at the desk in John’s workplace where they thrash out successive drafts. Here too are mementos of their work together. Photographs taken on the sets of various movies. A large police map of the streets of Los Angeles covers one wall. Authentic, it was used on the set of True Confessions—little black dots across its surface mark where crime-scene pins once stuck. On the opposite wall, a more serene scene: a blown-up photograph of Joan Didion standing in the shallows of a quiet sea holding a pair of sandals. Many photographs are of their daughter, Quintana Roo (named after a state in Mexico), now the photo editor at Elle Decor magazine. A recent addition in the workroom is a photograph of Quintana and Robert Redford, who costars with Michelle Pfeiffer in the newly released Up Close and Personal.

The interview that follows is a composite—partly conducted at the YMHA before a packed audience, partly at Dunne’s home on the East Side, with a written portion about the novel Playland added by the author himself.

INTERVIEWER

Your work is populated with the most extraordinary grotesqueries—nutty nuns, midgets, whores of the most breathtaking abilities and appetites. Do you know all these characters?

JOHN GREGORY DUNNE

Certainly I knew the nuns. You couldn’t go to a parochial school in the 1940s and not know them. They were like concentration-camp guards. They all seemed to have rulers and they hit you across the knuckles with them. The joke at St. Joseph’s Cathedral School in Hartford, Connecticut, where I grew up, was that the nuns would hit you until you bled and then hit you for bleeding. Having said that, I should also say they were great teachers. As a matter of fact, the best of my formal education came from the nuns at St. Joseph’s and from the monks at Portsmouth Priory, a Benedictine boarding school in Rhode Island where I spent my junior and senior years of high school. The nuns taught me basic reading, writing, and arithmetic; the monks taught me how to think, how to question, even to question Catholicism in order to better understand it. The nuns and the monks were far more valuable to me than my four years at Princeton. I’m not a practicing Catholic, but one thing you never lose from a Catholic education is a sense of sin and the conviction that the taint on the human condition is the natural order.

INTERVIEWER

What about the whores and midgets?

DUNNE

I suppose for that I would have to go to my informal education. I spent two years as an enlisted man in the army in Germany after the Korean War, and those two years were the most important learning experience I really ever had. I was just a tight-assed upper-middle-class kid, the son of a surgeon, and I had this sense of Ivy League entitlement, and all that was knocked out of me in the army. Princeton boys didn’t meet the white and black underclass that you meet as an enlisted draftee. It was a constituency of the dispossessed—high-school dropouts, petty criminals, rednecks, racists, gamblers, you name it—and I fit right in. I grew to hate the officer class that was my natural constituency. A Princeton classmate was an officer on my post and he told me I was to salute him and call him sir, as if I had to be reminded, and also that he would discourage any outward signs that we knew each other. I hate that son of a bitch to this day. I took care of him in Harp. Those two years in Germany gave me a subject I suppose I’ve been mining for the past God-knows-how-many years. It fit nicely with that Catholic sense of sin, the taint on the human condition. And it was in the army that I learned to appreciate whores. You didn’t meet many Vassar girls when you were serving in a gun battery on the Czech border and were in a constant state of alert in case the Red Army came rolling across the frontier. As for midgets, they’re part of that constituency of the dispossessed.

INTERVIEWER

You once said you only had one character. Is that true?

DUNNE

I’ve always thought a novelist only has one character and that is himself or herself. In my case, me. So at the risk of being glib, I am the priest in True Confessions and the criminal lawyer in Dutch Shea, Jr. I’ve certainly never been a cop or a priest or a pimp lawyer, but these protagonists are in a sense my mouthpieces. I like to learn about their professions, which is why I like doing nonfiction so much. I’m a great believer in the novelist being “on the scene,” reporting, traveling, meeting all sorts of people. You do nonfiction, you get to meet people you would not normally meet. I’m not a bad mimic and I can pick up speech cadences that I would not pick up if I didn’t hit the road.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think novels have a life of their own?

DUNNE

Before I began writing fiction I thought that was nonsense. Then I learned otherwise. Let me give you an example. In The Red White and Blue, I started off thinking the protagonist would be the Benedictine priest, Bro Broderick. I realized rather quickly that he could not be but that I was stuck with him as a character. He never really came to life until I finished the book and went back and inserted his diary, which he had left in his will to the Widener Library at Harvard. Then for three hundred pages or so I thought the leading character was the radical lawyer Leah Kaye, because whenever she appeared on the scene the book took off. Then when I got to page five hundred of this seven-hundred-fifty page manuscript I realized she couldn’t be the leading character because she had not appeared in over two hundred pages. It was only then that I realized that the narrator, who was the only survivor of the three major protagonists, would have to be the leading character. So novels do take charge of the writer, and the writer is basically a kind of sheepdog just trying to keep things on track.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say something about the germination of a book?

DUNNE

I think any time a writer tells you where a book starts, he is lying, because I don’t think he knows. You don’t start off saying, “I’m going to write this grand saga about the human condition.” It’s a form of accretion. When my wife and I were in Indonesia in 1980 or 1981, we ran into this man who had been a University of Maryland extension teacher during the Vietnam War. He was stationed at Cam Ranh Bay. These GIs would go off in the morning in their choppers and when they’d come back at night—if they were lucky—he would teach them remedial English. I made a note of it in my notebook, putting it away because I knew this was a really great way to look at the Vietnam War, and it turned up in The Red White and Blue. When I am between books I am an inveterate note taker. I jot things down mainly because they give me a buzz. I like to go to the library and take a month’s newspaper, say August of 1962, and read through it. You can find great stuff in those little filler sections at the bottom of a page. Then when it comes time to start writing a book, I sort of look through the stuff and see if any of it works. I also write down names. If you have a name it can set someone in place. I have a great friend in California, the Irish novelist Brian Moore. We were having dinner one night and Brian said that when he was a newspaperman in Montreal a local character there was named Shake-Hands McCarthy. I said, Stop! Are you ever going to use that name? He said, No, let me tell you about him. I said, No, I don’t want to know anything about him. I just want to use that name. So the name turned up in True Confessions. When I heard the name I had no idea when I was going to use it if, indeed, ever. But it was a name that absolutely set a character in cement. We had dinner with Joyce Carol Oates at Princeton once; she was saying that she does the same thing, that she collects those little fillers. She never knows when she’s going to use them; she just throws them in a file and oddly enough they do stick.

To get back to your question, Vegas is the one book for which I can actually pinpoint the moment when it started. I was trying to think of an idea, doodling at my desk while I was talking to my wife, and I drew a heart, then a square around the heart. I found I had written five letters: V-E-G-A-S. So I not only had a subject; I had a title.

INTERVIEWER

Why is the title of Vegas reinforced by the description “a fiction”?

DUNNE

Because I had a contract for a nonfiction book. I always thought of Vegas as a novel, but Random House said, It doesn’t read like a novel, and I said, A novel is anything the writer says the book is, and since I made most of it up, it can’t be nonfiction. So we ended up calling it a fiction. A lot of it is true. The prostitute did write poetry, although the poetry I used in Vegas is not hers. It was actually written by my wife, who as a child had memorized a lot of Sara Teasdale poems. I can write you bad poetry, she said. So there are two little poems in there that Joan actually wrote.

INTERVIEWER

What is your state of mind when you are writing?

DUNNE

Essentially, writing is a sort of manual labor of the mind. It is a hard job, but there comes a moment in every book, I suppose, when you know you’re going to finish and then it becomes a kind of bliss, almost a sexual bliss. I once read something Graham Greene said about this feeling. The metaphor he used was a plane going down a runway and then, ultimately, leaving the ground. Occasionally he had books that he felt never did leave the runway; one of them was The Honorary Consul, though in retrospect he realized that it was one of his better books.

INTERVIEWER

How much do you know about the end of a book?

DUNNE

When I did Dutch Shea, Jr., I knew the last line was going to be, “I believe in God.”

INTERVIEWER

Why did you pick that line?

DUNNE

Because that’s the line the man would say as he kills himself. I wanted that most despairing of acts to end with the simple declarative sentence, “I believe in God.” In The Red White and Blue I knew the last line was going to be either yes or no, in dialogue, and the penultimate line was going to be yes or no not in dialogue. The first line of Vegas is, “In the summer of my nervous breakdown, I went to live in Las Vegas, Clark County, Nevada.” I knew that the last line of that book would be, “And in the fall, I went home.” I don’t think it’s necessary to have a last line; I just like to know where in general I’m going. I have a terrible time plotting. I only plot about thirty pages in front of where I am. I once had dinner with Ross MacDonald, who did the Lew Archer novels about a California private detective. He said he spent eighteen months actually plotting out a book—every single nuance. Then he sat down and wrote the book in one shot from beginning to end—six months to write the book and eighteen to plot it out. If you’ve ever read one of those books, it’s so intricately plotted it’s like a watch, a very expensive watch.

INTERVIEWER

You have said that you have a lot of trouble with plotting a book. What makes it move forward?

DUNNE

I have no grand plan of what I’m going to do. I had no idea who killed the girl in True Confessions until the day I wrote it. I knew it would be someone who was not relevant to the story. I had always planned that. But who the actual killer was, I simply had no idea. Years before, I had clipped something from the Los Angeles Times in the small death notices. It was the death of a barber. I had put that up on my bulletin board. I was figuring out “now who . . .”—getting to the moment when I had to reveal who killed this girl, with not the foggiest idea who did it, and my eyes glommed onto this death notice of a barber. I said, Oops, you’re it. One must have enormous confidence to wait to figure these things out until the time comes.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have great affection for your characters?

DUNNE

You have to have affection for them because you can’t live with them for two years or three years without liking them. But I have no trouble killing them off.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a considerable shifting of gears in moving between nonfiction and fiction?

DUNNE

There’s a technical difference. I find that the sentences are more ornate and elaborate in nonfiction because you don’t have dialogue to get you on your way. Nonfiction has its ruffles and flourishes, clauses and semicolons. I never use a semicolon in fiction.

INTERVIEWER

Your latest novel is Playland. The background is the movie business.

DUNNE

I lived in Los Angeles and worked in the movie business from the mid-sixties until the late eighties, but except on the fringes, in The Red White and Blue, I had never written about Hollywood and the picture business in fiction. It was like an eight-hundred-pound gorilla. Sooner or later I was going to have to deal with it.

INTERVIEWER

Why did you set the Hollywood part of your novel largely in the 1940s rather than in the period you were working there?

DUNNE

Because I don’t think contemporary Hollywood is terribly interesting, and because I don’t want any sense of a roman à clef (is your so-and-so really so-and-so?). Mostly I wanted to reconstruct an era from a distance, an era that I kept on getting tantalizing glimpses of from people I knew or worked with who had been there in the 1940s and had not just been there but had been at the top of the heap.

INTERVIEWER

For example?

DUNNE

Otto Preminger. Joan and I once did a screenplay for him. He was an immensely cultivated man, but he was a tyrant with a volcanic temper. When he lost his temper, the top of his head—he shaved it with an electric razor sometimes during story meetings—would turn beet red. He screamed at most people who worked for him but never at us; he just got elaborately polite, and he would refer to Joan as “Mrs. Dunne,” drawing it out for half a dozen sibilant syllables. He brought us back to New York to work on the script. He said it would only take three weeks tops, but three months later we were still there—in this tiny apartment on Fifth Avenue with our four-year-old daughter and a different babysitter every day. Our daughter called Otto, to his face, Mr. Preminger with no hair, which he took with good grace. We finally said we were going home for Christmas and we would finish the script there, and Otto said, I forbid you to go. It was an extraordinary thing to say. We thought he was kidding, but that was the way the studios had always operated and he saw nothing wrong with it. We went back to L.A. anyway and he threatened to sue us for two million dollars. He simply could not understand our lack of deference. It worked out. He paid off our contract at forty cents on the dollar. It was the kind of punishment the old studio system would have exacted. But we always stopped by to see him when we came to New York, because if you were not working for him he was a charming man.

INTERVIEWER

Who else?

DUNNE

Billy Wilder. In the mid-eighties he asked me to do a screenplay with him for an idea he had about a silent movie star playing Christ in a biblical epic. The twist was that the movie star was a dissolute drunk who was screwing everybody on the set, including the actress playing the Virgin Mary, while the actress playing Mary Magdalene spurned him, another twist. Billy wanted him to repent at the end of the picture and actually walk on water—a gag he would set up throughout the picture and then pay off at fade-out. Nothing came of the idea, but we had some funny meetings because Billy has perfect pitch for truly hilarious bad taste. This was a man who won seven Oscars, and he kept them in a closet at his nondescript office on Santa Monica Boulevard. He usually worked with Izzy Diamond, but Izzy was dying or had just died and Billy always wrote with a collaborator, which is why he had asked me to work with him. Raymond Chandler had worked with him on the script for Double Indemnity and they had detested each other, but they wrote a great screenplay together, which proves you don’t always have to like the people you work with. I would ask him about the days of the red scare and the blacklist and he had this interesting take, which was that no one very good actually joined the Communist party, it only attracted the second-raters. Of course Billy had the most famous line about the Hollywood Ten (or the Unfriendly Ten as they were called) when they had to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Only two of them were talented, he said; the other eight were only unfriendly. We never wrote the script. I had to finish The Red White and Blue and the time did not work out.

INTERVIEWER

Did you work with George Cukor?

DUNNE

I knew George but never worked with him. We were at a dinner party one night at Peter Feibleman’s house. Lillian Hellman was the hostess and the guests were George, Olivia De Havilland, Willie and Tally Wyler, and then a younger generation—Peter, Mike and Anabel Nichols, Warren Beatty and Julie Christie, and Joan and I. We were very much made to feel that we were at the children’s table, there to be seen but not heard. George and Willie and Lillian were all to die in the next few years, and it was as if they knew this was the last time they would see each other and they wanted to settle a lot of old scores. And boy, did they! The interesting thing was that they all liked the old studio system, and the monsters like Harry Cohn and Sam Goldwyn. At one point in the evening I made the mistake of asking George about Howard Hawks, my own personal favorite of the old-time directors, and he rose up and said, I despise Mr. Hawks and I loathe his pictures. Betty Bacall once told me Hawks was a famous anti-Semite; he would talk to her about Yids, not knowing that her real name was Perske, and he wasn’t supposed to like gays much either, so needless to say George had no use for him. He’d talk about Garbo and Kate Hepburn, both of whom would stay with him at his house in the Hollywood Hills when they came to L.A. I remember once going to a party at his house. He wasn’t giving it—I don’t think he was even there—he had just lent this perfect little jewel of a house to a studio for a press party for some out-of-town distributors. The studio—it was Fox—had dressed the pool area and put up a tent. At the end of the evening I went to get my car, and as I was waiting for the parking boy, I picked a lemon off a potted tree by the entrance to the house. It occurred to me that it was out of season for lemons, and when I looked at it, I saw that it had been stamped with the word Sunkist. What the studio had done was wire lemons to the trees. That’s what studios did. They tried to control everything, even the environment.

INTERVIEWER

Blue Tyler’s character in Playland seems to have elements of Natalie Wood. Did you know her?

DUNNE

Not when she was a child star. When we first got to California, she was just beginning to cross over from a child actress to a grown-up movie star. She had never really been a child star in the sense that Shirley Temple was a star, able to carry a picture all by herself (the way Macaulay Culkin can today), but the transition from child actress to woman movie star was one that only Elizabeth Taylor had made successfully. Margaret O’Brien hadn’t made it and neither had Shirley Temple, really. Only Taylor and now Natalie. About this time there was a huge eight- or ten-page photo spread on her in Life magazine. I remember one of the pictures especially, of Natalie in the conference room at the William Morris Agency, sitting at this enormous conference table, this tiny slip of a young woman surrounded by her retainers—her agent, Abe Lastfogel, who was the head of the Morris office, her public-relations people, and her accountants, all of these middle-aged men focused on managing the career of this twenty-one-year-old child. We met her a few years later. She was an extraordinarily generous woman. She paid for a shrink for her assistant, a young man named Mart Crowley, who wrote The Boys in the Band. Mart was a friend of ours and through him we became acquainted with Natalie and her husband Richard Gregson, and then later with R. J.—Robert Wagner, called R. J., who was Natalie’s first and third husband—when they remarried. I asked her once what it was like being a child star and she said, They take care of you—they being the studio. One thing I remember about Natalie was how astute she was about the business of Hollywood, about her own worth and the worth of everyone else. She understood money and investment the way a French bourgeoise does. And like most people in Hollywood she was a fantastic gossip, knew everything, where all the bodies were buried, and under how much dirt. When she died, we went to her funeral, a nastily hot late fall day, with the paparazzi hanging over the walls of the cemetery (the same one where Marilyn Monroe was buried). And afterwards, we stopped by her house, and there I remember two things. First was the family Sinatra sitting side by side on a couch—Frank, big Nancy, little Nancy, Tina, and Frank Jr., as if it were a funeral in Palermo. The other was Elizabeth Taylor, who in the absence of the hostess—Natalie—had taken charge, greeting everyone and to all saying, I am Mother Courage.

INTERVIEWER

How much of this material made its way into Playland?

DUNNE

Specifically only two things really—the photo of Natalie Wood in Life at the conference table in the William Morris office, and then Natalie saying that the studio took care of her. This is not to suggest that she was the model for Blue Tyler, because Blue was sui generis, and when I got to know Natalie, she was a twice-married young mother. But with all these people, Otto and Billy and George and Natalie, there was the sense of the studio controlling their lives, their destinies in every aspect, and the concomitant sense that however the studio’s subjects—the actors, directors, producers, and writers under contract—might have bridled under the idea that the studio knew best, they did not ever really rebel. There is a line in Playland when Arthur French says rather sadly about some lie the studio put out, “People believed studios in those days.” What he meant of course was that people were so trusting they even believed the untruths, as they were supposed to. That period, the late 1940s, was the last time that the studios exercised total control and had real power. Television was just a dark cloud on the horizon and the government had not yet forced the studios to divest themselves of their theater chains. A studio’s power was so absolute in those days that it simply would not have permitted a contract star of the caliber of Julia Roberts, say, to marry someone like Lyle Lovett, a funny-looking below-the-title singer.

INTERVIEWER

So you set out wanting to do a novel about Hollywood in this period?

DUNNE

Actually, no. I started out to do a novel about Blue Tyler’s daughter. I thought of her as a contemporary Sister Carrie, but I couldn’t make the book work. Then Joan and I were asked to write a screenplay about Bugsy Siegel, which we turned down. But there was something about the idea that intrigued me and I suggested a story about a New York gangster who comes to Hollywood and falls in love with Shirley Temple. Not Shirley Temple herself, God knows, but a major child star, seventeen years old, trying to cross over into grown-up roles, with the vocabulary of a longshoreman and the morals of a mink. We wrote the screenplay but it fell between the cracks when the studio we wrote it for was acquired by another studio, which in Hollywood is the kiss of death for projects initiated by the acquired studio. The executives at the new place are scared enough of getting burned by their own projects without having to take the fall for failed projects from another studio. They go out of their way to bad-rap the other studio’s projects. Much of the interplay between the loathsome director Sydney Allen and my narrator Jack Broderick is a direct result of this experience, although I had no idea at the time that I was going to make use of it. Then I lost a year to medicine. First I had open heart surgery, and just as I was recovering from that, I got blood poisoning.

INTERVIEWER

And it was during that year’s hiatus that Playland took shape? Or another shape?

DUNNE

Yes. I rethought it. I had this murder book I had acquired while doing another picture, the film of my novel True Confessions, which had a crucial scene in a morgue. Now I had never been to a morgue, and so one night at two o’clock in the morning the director Ulu Grosbard and I were taken inside the morgue, absolutely against regulations, by a homicide detective. We saw the cold room, where the corpses are kept, and we saw autopsies being performed and the decomp room, where decomposing bodies are stored—the most God-awful smell, I had to smoke a cigar to get past it. It was quite an experience. Afterward, the homicide cop let us look through old murder files. There was an implicit quid pro quo attached—he wanted to be a technical advisor on True Confessions and if we saw something else that hit our fancy, money would change hands. It was on this expedition that I read the murder book of an unsolved 1944 murder. The “murder book” is what cops call the history of an investigation, containing police reports, forensic photographs, autopsies, the questioning of witnesses and suspects, correspondence, updates, all the way to the final disposition of the case—in some instances the gas chamber. The book in this case was still open, as are all unsolved murders. Several things attracted me to it. First was that the victim, who was only seventeen, had gone to the same school my daughter was attending. Second, the apartment building where she lived was one I knew well—it was the home of friends of ours. And third, Shirley Temple was a schoolmate of the victim—her telephone number was in the victim’s address book. This was ten years before I even began thinking of writing a novel about a former child star. There was also a riveting forensic photo of the battered and naked girl on a gurney in the morgue. Someone had placed a doily over her pubic area; it was an absurd daintiness considering the circumstances of her death and the ravages of the assault visible on the rest of her body. The cop said I could have the book for twenty-four hours, so I took it, got it photocopied and the forensic pictures photocopied. It was back in the file the next evening. I suppose one might call the entire endeavor an example of off-the-books free enterprise.

INTERVIEWER

And this is the murder that appears in the book?

DUNNE

Considerably rewritten to accommodate the narrative. I had the file for years and didn’t know what to do with it. I was not interested in it by itself as a discrete literary endeavor and I did not know how to fit it in anyplace else. What intrigued me mostly were the loops and turns of a criminal investigation, the number of tangential lives it happened to touch, and how in the course of the detective work a mosaic of petty treasons, moral misdemeanors and quiet desperation emerged that had nothing to do with the murder in question but only with permutations of life itself.

INTERVIEWER

Again, it’s interesting how much of the book is based on fact.

DUNNE

Fact is like clay. You shape it to your own ends. For example, I wanted a namer of names before the House Un-American Activities Committee who was a sympathetic, and unrepentant, character. So I invented Chuckie O’Hara. Gay. A director. An admitted communist before HUAC. But then a wounded war hero in World War II. And finally someone who purged himself by naming names and then lived out the rest of his days without guilt. It is about Chuckie, at his funeral, that I wrote, “Whatever his transgression, in the end he was one of them. Membership in the closed society of the motion picture industry is almost never revoked for moral failings.” That is a coda for Hollywood even unto the present day.

INTERVIEWER

So Playland is about this closed society?

DUNNE

I suppose so, yes. Among other things. Like, what is truth? Because no one in the book ever really tells the truth. Half-truth is the coin of the Hollywood realm.

INTERVIEWER

Whatever happened to Blue Tyler’s daughter, the one you originally thought the book was about?

DUNNE

She appears for the first time on Playland’s last page.

INTERVIEWER

To go back a bit, you started off writing for Time magazine. Was that helpful? Why did you leave?

DUNNE

It had to do with Time’s coverage of the Vietnam War. The Time bureau chief, who was doing the war out of Hong Kong before he moved to Saigon, was a guy called Charlie Mohr. Charlie was one of the first to say this war isn’t going to fly. He was by no means a liberal; he just saw it on the basis of his reporting. One week we did a wrap-up on the war and Charlie sent in a file, the first sentence of which was “The war in Vietnam is being lost.” It was a Friday night, and I said to myself, Uh oh, this is never going into the magazine. I had dinner with Joan and I said, I think I’m going to call in sick. She said, No, you’ve got to go back and do it. So I went back and did the story based on the file, trying to put in the qualifiers that would get past Otto Fuerbringer, and went home around three in the morning. The next morning the edited copy was on my desk and on the top it said, “Nice. F.” It was the complete opposite of what Charlie’s file was and what I had written. Redone from top to bottom. Charlie quit and eventually went to The New York Times. I said I no longer wished to do Vietnam. I ended up doing Lichtenstein, the Common Market, realizing that my days there were numbered. Joan and I got married in January. In April I said, “Do you mind if I quit?” And that was it. However, I liked Time. It taught me how to meet a deadline, to write fast. It’s wonderful training. Writing for Time is like writing for the movies—ultimately what you write is not yours, because you’re not in charge of what you’re doing.

INTERVIEWER

Joan worked for the Luce people for a while, didn’t she?

DUNNE

For Life. She had published her first novel Run River and then the essays in Slouching Toward Bethlehem and was about to publish Play It As It Lays when she got the offer to do a column for Life. I said, “Don’t do it. It’ll be like being nibbled to death by ducks.” She lasted seven columns. It was about that time we got asked to do our first movie, so everything worked out.

INTERVIEWER

Had you thought of writing for the screen?

DUNNE

As a matter of fact I started a novel about Hollywood when working for this industrial design magazine after coming out of the army. I knew nothing about Hollywood and had never been there. It was called “Not the Macedonian” and the first line was “They called him Alexander the Great.” That’s as far as I ever got. I used to write a lot of first lines of novels; the second line was the problem.

INTERVIEWER

How did you come to be asked to do a screenplay?

DUNNE

A wonderful man named Collier Young . . . he was Virginian, I think, and had married four times. Wives two and three were Ida Lupino and Joan Fontaine. He lived up on Mulholland Drive in a place he called the Mouse House. One year his Christmas card said, “Christmas greetings from the Mouse House, former home of Ida Lupino and Joan Fontaine.” He was the creator of the television series with the detective, Raymond Burr in the wheelchair. He got fired three segments into it, but he still got paid every week because it was his idea. In 1967, the same year the South African doctor Christiaan Barnard did the first heart transplant, Collie came to us and said, I think there’s a movie here. We worked out a story in which a Howard Hughes character, Hollis Todd, needs a heart and his underlings kill a former Olympic athlete who had become a paraplegic after an automobile accident and transplant his heart into Todd. All the main characters had last names for first names, I suppose because Collie’s name was Collier Young. To our amazement it sold to some studio, I think it was CBS, which paid us fifty thousand dollars. I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. The picture was never made, though the screenplay was novelized and called The Todd Dossier. The man who wrote the novelization basically took our treatment and just added onto it. That book is still in print. It’s sold in seventeen foreign languages.

INTERVIEWER

So you were on your way?

DUNNE

That got us into the Writers Guild and once you are in the Guild you can work. The first screenplay we wrote that was produced was The Panic in Needle Park. My brother Dominick Dunne took it to various and sundry places and it was finally bought by Joe Levine. We were told you had to sell to Joe Levine with one line. The one line that sold it to Joe was “Romeo and Juliet on junk.”

INTERVIEWER

How do you and Joan work when you’re doing a screenplay?

DUNNE

With The Panic in Needle Park I wrote the first draft in about eighteen days. Joan was finishing up her novel Play It As It Lays. When I finished she went over the draft and did her version. Then we sat down and put together the version we handed in. It’s generally worked that way with every script we’ve done. The version the studio sees is essentially our third draft. A movie is so much more schematic than a book; you only have a hundred and twenty pages, because the rule of thumb is one page equals one minute of screen time, and movies shouldn’t be over two hours long.

INTERVIEWER

Why in writing for the screen is a film rarely done without collaboration?

DUNNE

I’m not sure that’s so. Bob Towne works by himself. So does Alvin Sargent. Bill Goldman. Larry Gelbart. But I cannot imagine doing a screenplay by myself because so much of it is talking it out first so you know where the high points are. With a book you can often do riffs, which you can’t really do in a movie unless you’re a writer-director. We have never wanted to direct pictures. By the time we wrote our first screenplay we had written maybe five books between us, which was what we wanted to do because we were our own bosses—with a book you are the writer, director, editor, cameraman. But I can say without equivocation that the movies have supported us for the past twenty-six years. We’ve written twenty-three books between us and movies financed nineteen out of the twenty-three. And we like doing it.

INTERVIEWER

Why is it that it’s looked upon with such detestation by people who consider themselves serious novelists and who have gone out there to make the money? Do you think they’ve actually had quite a good time and just don’t want to admit it?

DUNNE

Yes, I do. I’ve never believed in Hollywood the destroyer. The naysayers are people who would have been destroyed at Zabar’s if they never went west of the Hudson. I simply never believed it. Faulkner wasn’t destroyed. Hemingway wasn’t. O’Hara wasn’t.

INTERVIEWER

Have you worked at doctoring other people’s scripts? Is it worth it?

DUNNE

Yes. Six figures a week if you’re any good, hundred grand at the minimum. We’ve all done it. For a long time I couldn’t understand why they paid so much. If you get a six-figure weekly fee you think it’s more money than there is in the world. The studio, however, is looking at a forty-million-dollar picture, and if it doesn’t get done they are out all that money. So they will throw in writers at a hundred and fifty grand a week to put in jokes, put in scenes just to get the picture on . . . they always answer with money. The worst thing that can happen is that the project gets flushed, because then they lose all the money spent for development, which can add up to millions of dollars.

INTERVIEWER

Can you give a few examples of screenwriting at its best?

DUNNE

Chinatown. Robert Towne. It was a wonderfully intricate, well-worked screenplay with an enormous amount of atmosphere. Another one: Graham Greene and Carol Reed in The Third Man. That is the best collaboration between writer and director I can think of. It is the one movie Joan and I always watch before we start a script because it is so brilliantly worked out. It’s very short, an hour and forty-five minutes. What else? I wouldn’t say it’s one of the best, but Truman Capote’s Beat the Devil. Oh, and Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, a terrifying and funny screenplay; I liked it much more than Pulp Fiction, which just seemed to rework Reservoir Dogs.

INTERVIEWER

I assume a great screenplay can be destroyed by direction and by acting.

DUNNE

There’s no such thing as a great screenplay. Because they are not meant to be read. There are just great movies.

INTERVIEWER

So when you talk about a good screenplay you’re really talking about what directors and actors did with it. There’s no way one could have a recognizable style as a screenwriter?

DUNNE

What the screenwriter is ceding to the director is pace, mood, style, point of view, which in a book are the function of the writer. The director controls the writing room, and it’s in the editing room where a picture is made.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a formula to screenwriting?

DUNNE

Not in general. Specifically perhaps. Bill Goldman once said that you start a scene as deep in as you can possibly go. You don’t start the scene with somebody walking through the door, sitting down, and starting a conversation. Bill said you start a scene in the middle of the conversation, which I think is a very astute observation.

INTERVIEWER

Would you divide the screenplay into acts, as some people do?

DUNNE

The studio people talk about first act, second act, third act. We don’t do it when we’re writing. When we were doing True Confessions, Ulu Grosbard came up with a wonderful take. He said the script was a “one-span bridge” and it needed to be a “two-span bridge.” I knew exactly what he meant. The screenplay we had went up once and came down instead of going up twice and then coming down. In other words, we needed a third act.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a connection between a writer who has literary merit and a screenwriter? Is a screenplay such a departure from the novel that one hardly needs to know how to write to become a screenwriter?

DUNNE

What troubles me is that screenwriters today seem to have had no life other than film school. They’ve rarely been reporters; they’ve rarely gone out and experienced a wider world. I had the army, I was a reporter for ten years, I’d been to Vietnam—not for long, but long enough to know I didn’t like to get shot at—I covered labor strikes and murder trials and race riots. The entire frame of reference the younger screenwriters have is other movies. It’s secondhand. And if you steal a moment from an old movie, you can probably bet that the moment you stole was probably itself stolen in the first place.

INTERVIEWER

Would you recommend to a young person a career as a screenwriter?

DUNNE

I’m not sure I would, because you’re really not a writer and you’re really not a filmmaker. I once said that the most you could aspire to be as a screenwriter is a copilot. If you are going to write movies full-time and you don’t write books like Joan and I do, then you better aim to be a director because that’s the only way you’re going to be in charge, and being in charge is what writing is all about.

INTERVIEWER

You sound downbeat about screenwriting.

DUNNE

Look. It pays a lot and it’s fun. It’s better than teaching and better than lecturing, the other compensatory alternatives for writers without jobs. But it is hard fucking work. On our last script, Up Close and Personal, it took eight years to get it on. We quit three times. Two other writers came on board and left. In all we wrote twenty-seven drafts before a frame of film was shot, then we worked for seventy-seven days during the shoot, rewriting. The picture was originally supposed to be about Jessica Savitch, a golden girl for NBC News who flamed out and died in an automobile accident. She was a small-town girl with more ambition than brains, an overactive libido, a sexual ambivalence, a tenuous hold on the truth, a taste for controlled substances, a longtime abusive Svengali relationship, and a certain mental instability. Disney was the studio and the first thing Disney wanted to know was if she had to die in the end. And they weren’t crazy about an interracial love affair she had, nor her abortions, nor the coke, nor the lesbianism, nor the gay husband who hung himself in her basement, nor the boyfriend who beat her up. Otherwise they loved the idea. Making that work was work. Eight years worth. Twenty-seven drafts worth. Thank God it was a hit.